Myan-marred Relations

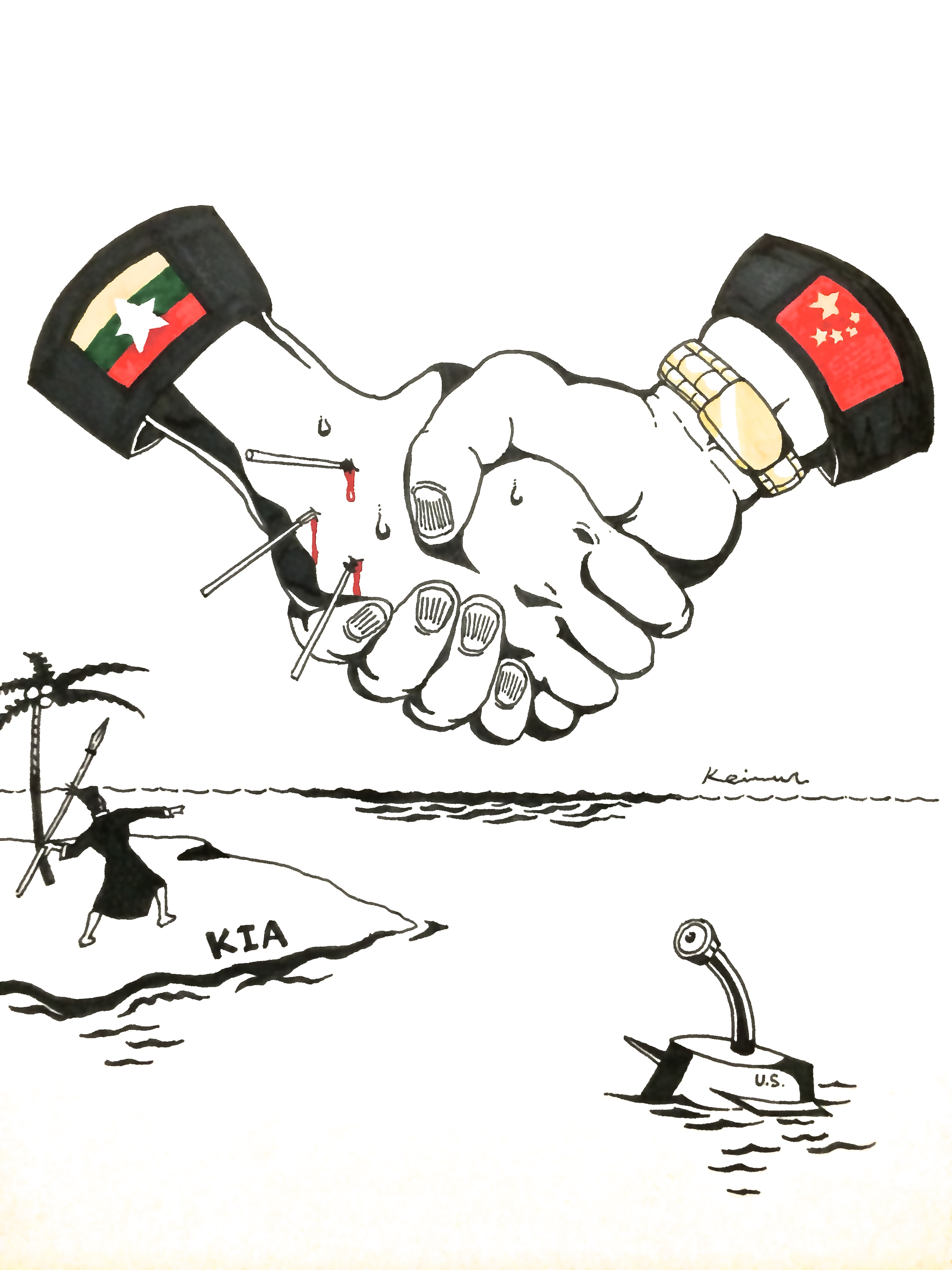

When President Thein Sein of Burma announced on September 30, 2011 that he was suspending construction on the Myistone Dam “to respect the people’s will,” Chinese officials were “shocked,” “surprised,” and “utterly unprepared” to handle such a democratic decision. The $3.6 billion project, brainchild of the state-owned China Power Investment (CPI), would have delivered 90 percent of the potential 6,000 megawatts generated to cities in China’s Yunnan province. But it also would have flooded an area the size of Singapore (26,238 hectares), displacing up to 12,000 people in 47 villages. Even before construction was suspended, approximately 2,500 people had already been pushed from their homes. A corporate social responsibility report released by CPI-controlled Ayeyawady Confluence Hydropower Co. (ACHC) late last year was denounced as propaganda by the dam’s opponents, one of whom added, “We, the Kachin people, are not enjoying the benefits [of the dam]… Everything China did was for their own good name. They are trying to improve their reputation…”

Burmese antipathy towards the Chinese is anything but new. Though state relations between Burma and China had been pauk phaw (fraternal) since the 1950s—Burma being “the only friendly non-Communist territory through which Chinese Communists [could] come and go”—relations began to sour in the late ‘60s. When the Cultural Revolution began in China in 1966, reverberations through Burma’s Chinese community resulted in retaliatory legislation from the Burmese government, who forbade students from wearing Mao badges and reciting Mao’s sayings. On June 22, 1967, a group of school children at the Rangoon No. 3 National Elementary School defied the regulations, resulting in a fight between students and faculty. The brawl eventually ended, but students continued to wear badges and recite quotations. Burmese mobs launched attacks on various Chinese institutions in Rangoon, which by June 27 escalated into a full-blown riot. Dozens of Chinese associations were destroyed, 31 members were killed, and several diplomats were assaulted.

Beijing made five demands and used the Burmese Communist Party, an opposition group founded by leading Burmese nationalists, to undermine government leader General Ne Win, calling him “the Chiang Kai-shek of Burma.” Rangoon ignored China’s demands and asserted the BCP had no right to interfere in Burma’s internal affairs. Diplomatic ties were cut and Rangoon took measures to weaken China’s influence within the country. It was not until Deng Xiaoping visited Burma in 1978 that relations were fully normalized.

As China sought greater economic modernization in later parts of the 20th century, its policy towards Burma shifted from supplying political support to emphasizing trade. By 1985, China-Burma trade was at an estimated $1 billion (USD) a year – not including revenues derived from narcotics trafficking through Burma’s slice of the Golden Triangle. In 1988, the Burmese junta abandoned the Burmese Way to Socialism, which had by this time proved disastrous economically, and implemented several market liberalization reforms. But this was at the very moment the international community made the junta’s ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) a pariah in response to its brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in August of that year. When China was sanctioned as a result of similar brutality taken against its own student protesters in 1989, interdependence between the two countries increased. Military aid in particular rose dramatically, the Chinese providing $2 billion (USD) in technical support and material goods, including jet fighters, tanks, ammunition, naval vessels, armored personnel carriers, and missiles. China became the Burmese army’s largest weapons supplier, and remained so through the 1990s.

This de facto support for the tatmadaw (Burmese armed forces) won China no friends among several ethnic minority populations (particularly the Kachin and the Shan) on whose land it extracted resources. Armed conflict between ethnic groups and the state have colored Burma’s political landscape since 1949. Between 1961 and 1989, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), operating in its namesake state, grew from a small band of 100 guerillas to a sophisticated army of 21 battalions. While the Shan State Army had less success, it still experienced widespread support, especially in the Shan’s political and economic heartland along the Burma-China border. Control by insurgents didn’t stop the Chinese from trading in cross-border regions, and it wasn’t until the Burmese army recaptured those territories in a 1987 offensive that Beijing decided to trade directly with Rangoon. Having lost a significant source of revenue, armed ethnic groups redoubled their resolve against the Burmese army. Between 1987 and 1994, counter-insurgency campaigns against both ethnic and communist groups along the border triggered an exodus of refugees into China and India.

In 1994, the government of Burma brokered a ceasefire agreement with several major armed groups. But rather than address the needs of ethnic Kachin and Shan whose lives had been disrupted by fighting, the government allowed what was left of the local economy to be eroded by an influx of Burmese and Chinese firms. Small businesses shuttered and migrant workers brought in from China worsened already high unemployment rates. Twenty percent of Kachin state’s land was set aside for mining and the Burmese government announced plans to build seven dams along the N’Mai and Mali Rivers, which would be financed, of course, by China.

This decision only exacerbated the tension in the region. On June 8, 2011, the KIA intimidated a member of the Burmese army at the Tarpein Hydropower Project, a joint venture between the Burmese Ministry of Electric Power and Chinese Datang Hydropower Developing Company. On June 9, the Burmese army attacked a strategic KIA post at the location of yet another Chinese-funded hydropower dam, effectively violating the 17-year old ceasefire.

Chinese participation in the Burmese economy—and civil conflict—at the people’s expense has delegitimized Beijing in the eyes of Burmese citizens. China has argued it is providing employment and crucial infrastructure to a truly underdeveloped region. However, ethnic minority activists are skeptical that the benefits of China’s economic activity in Burma will trickle down as far as officials claim. As the Myitsone Dam episode shows, popular opposition to Chinese presence has weakened Beijing’s pull vis-à-vis Naypyidaw (Burma’s post-2006 capital). But what’s perhaps most indicative of this diminished position is that China’s foreign policy towards Burma appears to be inoperable in a non-authoritarian context. Several scholars have noted that Burma’s political and economic reforms have only complicated relations with China, not to mention that Naypyidaw has improved relations with several countries, chief among them, the United States

The United States broke diplomatic ties with Burma in 1990 and ramped up rhetoric against the Burmese state throughout the 2000s. Sanctions were imposed by Washington, first in 1990, but again in 1997, 2003, 2007, and 2008. It was thanks to the United States that Burma became an isolated state and had no choice but to accept deals offered by China and its ilk. But as of 2009, things began to change.

The SPDC started attempting to engage with the United States diplomatically around 2006, but the September 2007 crackdown on anti-regime protests, the response to the 2008 cyclone (in which the U.N. Responsibility to Protect principle was very close to being invoked) and the neither free nor fair 2010 elections made it difficult for Washington to accept friendlier terms. Instead, the United States maintained a “road map” strategy, where unless progress was made towards realizing the US vision of a “unified, peaceful, prosperous, and democratic Burma that respects human rights,” relations had to remain icy.

Still, though little progress had been made towards those objectives, the Obama administration decided to revisit its Burma policy and institute a strategy of “pragmatic engagement.” Initially, China seemed indifferent to a closer relationship between the United States and Burma; it was aware its interests might be hurt by democratization, but was glad to have the blame for perpetuating a brutal regime toned down. Yet when the Obama administration suggested its foreign policy would “pivot” (rebalance) to Asia in 2011, many in Beijing began to see the changing US-Burma relationship as part of a larger “containment” policy.

Indeed, concern among Chinese policy analysts grew as relations between the United States and Burma improved at a dazzling pace, starting with quasi-civilian President Thein Sein’s inauguration that same year. Thein Sein’s somewhat reform-minded agenda—freeing political prisoners, easing press censorship, allowing Aung San Suu Kyi to run for and assume office—enabled the United States to incorporate more carrots into its Burma policy without invoking criticism from the American electorate. So while alarm bells rang for the Chinese at the announcement of the Myistone Dam project’s suspension, the United States was pleased—not least because it had funded the very civil society groups that secured this outcome.

In addition to advocacy and peer pressure tactics, the United States has tried to promote democracy in Burma by funding several educational, political, and cultural initiatives. From 2000-2010, the State Department financed a scholarship program for Burmese refugees to study at Indiana University. In 2009, a diplomatic cable from the US Embassy in Yangon reported, “with [U.S. government] support the Burma Laws Study Group trained 20 peasants and laborers from Rangoon Division and Rakhine State on labor laws and rights in Rangoon before sending them back to their home communities to conduct labor workshops.” Earlier that year, the Embassy in Jakarta sponsored a speaker symposium and photo exhibition in order to “increase public awareness on the Burma human rights situation and democracy struggle.” Many cite this sort of support as crucial to the opposition movement in Myanmar, without which it might not have the social capital or technical capability to challenge the regime.

In September 2013, the Chinese newspaper Renmin Ribao stated, “Following its opening, Myanmar has become a main battleground for the world’s major powers, and the Myitsone project has become a bargaining chip in the resulting geopolitical struggle… Some analyses point out that Western countries… will first have to ruin the Sino-Myanmar relationship in order to expand their influence in Myanmar and demonizing the Myitsone project is an opening.”

On the other hand, some argue the United States’ policy towards Burma does not have to exclude China necessarily. In fact, as recently as January 2014, the United States and China listed Burma as an area for possible cooperation. This announcement suggests the idea implied by the Renmin Ribao’s statement, that involvement in Burma is a zero-sum game, should be somewhat qualified. In fact, it is entirely plausible that China could carry on with its infrastructure projects, while the United States exports technical advice on governance and financial systems, things the Burmese have complained “the Chinese were unable, or unwilling to provide.”

Deserved or not, reform in Burma has been called Obama’s “greatest foreign policy success,” but recent events suggest the situation might again be de-stabilizing. Dozens of peaceful political prisoners remain in jail and many that have been freed are subject to rearrest at any point. The death of a journalist in military custody last October became a symbol of the government’s renewed “war on the press.” Burmese refugees in Thailand, of which there are 150,000, are still too fearful to return home.

To a certain degree, the Burmese government has demonstrated a willingness to accept external involvement in its economic and political affairs. As the humanitarian situation in the country remains uncertain, it will be necessary to condition assistance on concrete progress, a strategy that will only work if the international community operates in concert.

Going forward, there seem to be three potential trajectories in the triangle of US-Burma-China relations. First, there’s the rather pessimistic outlook that Chinese firms will operate on the assumption that as long as they pay their rent, they don’t have to make actual concessions to the communities in which they work. Second, there’s the more optimistic view that the United States and China will specialize their development activities without ever coming into conflict. Last, there’s the more nuanced perspective that the United States and China will have to engage in a dialogue about what kind of social, political, and economic environments they want to emerge in Burma. Democratization is a messy process that sows some political instability, but enabling autocracy is a bad reputation to have in this day and age.

At the time of writing, Aung San Suu Kyi, parliamentarian and chair of Burma’s National League for Democracy, is set to make her first official visit to China. Presently, the motivation for the trip is unclear, but its outcome will undoubtedly be an indication of the future Burma-China relations. Will Aung San Suu Kyi, a favorite of the West, remain an outspoken champion of political freedom? Or will she acquiesce to China’s terms in the name of securing much-needed development assistance? The United States must wait with bated breath.