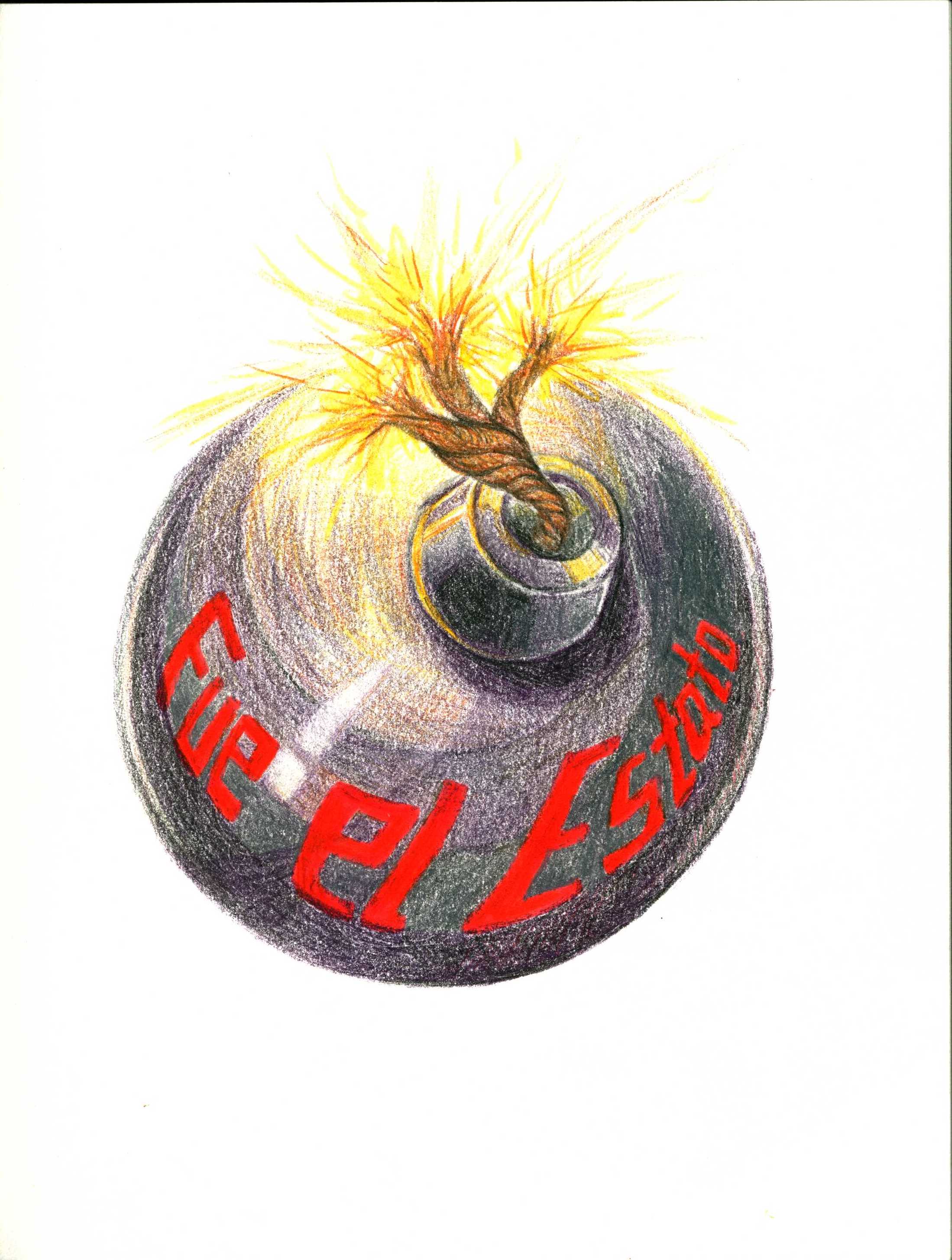

"It Was The State"

The disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Normal School in Iguala, Guerrero on September 26th, 2014 lit the fuse that by November 8th was igniting the doors of Mexico City’s National Palace. Thousands of protesters gathered in the Zocalo of Mexico City, chanting “Fue el Estado”: “It was the State.” As the ornate baroque wood of the Palace, witness to almost four centuries of Mexican politics, was consumed in flames, the protesters’ cries were vindicated. The image created by a few instigators legitimized the protesters’ chant by its dramatic and symbolic force – for watching the magnificent edifice of the federal government in flames, it seems obvious, almost intuitive: yes, it was the state.

However, looking away from the flames and into the ashes of Ayotzinapa – those of the bodies of the 43 students and the metaphorical ones of the Mexican government’s legitimacy – it becomes more difficult to understand and justify such a statement. The meaning of “the state” in the context of Mexico has become extremely cloudy after the events of Ayotzinapa, which saw the blending and collusion of local authorities, extra-legal groups, and party politics on a level rarely seen before. In fact, the very power of Ayotzinapa is articulated in “Fue el Estado” as referring to multiple levels of the political spectrum. The use of this national analytical category and international protest narrative may have significant implications on the outcome of this tragedy, as well as the future of Mexican politics and democracy. Such an ambiguous and apolitical slogan does not adequately explain the tragedy of Ayotzinapa. “Fue el Estado” ignores links between different levels of governance and chains of complicity, preventing the direct judgment of those responsible for the killings in its sweeping generalizations. Though it may express the emotions of thousands, it will likely only lead to a rebellious spiral – a dead end – and future collective frustration instead of concrete political change. The burning doors do not invite future constructive debate between the Mexican government and its people. Thus, careful and complete understanding of “the state’s” involvement in Ayotzinapa allows for a targeted governmental response to the disappearance of the 43 students, as well as more productive public mobilization and activism.

Thousands of protesters gathered in the city center the night of November 6th in response to the most recent press conference held by the Attorney General’s office earlier that afternoon, where Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam presented a report on the Ayotzinapa investigation. According to the official narrative, on September 26th, the mayor of Iguana, José Luis Abarca, ordered a direct attack on the Ayotzinapa students, allegedly in an effort to prevent them from disturbing his wife’s political event. After the students were fired on by municipal police, which resulted in six deaths, the remaining students were openly handed off to members of the local drug band, Guerreros Unidos, who loaded them into trucks and drove off. Three days prior to the press conference, the fugitive mayor and his wife were detained by a unit of federal police in a run-down abandoned house in the working-class district of Iztapalapa in Mexico City. Attorney General Karam then related that, according to the recently acquired testimony of the drug gang members, the 43 students had been burned in a garbage dump in Colula, Guerrero for over 15 hours. Their remains were collected in plastic bags and then dumped into the nearby river; some of these bags have been located, containing teeth and bone remains. The ashes of the garbage dump were sent by the federal government to a laboratory in Austria where they hope to extract mitochondrial DNA in order to verify the identities of the students. Perhaps most tragically, the 43 students of Ayotzinapa are the latest casualties of violence linked to organized crime in Mexico that has, to date, claimed almost 100,000 lives in Mexico. The several mass graves discovered in the same state of Guerrero during the past two months through the Iguala investigation, as well as the others found in the past, attest to the perpetual state of crisis that Mexico has existed in for the past two decades. The entire country has become a graveyard of bodies and souls of the living that languish in sadness and anger. However, these emotions have never before ignited federal buildings in the nation’s capital. It is the role of the “state” that Karam represents, at all levels, which lit the flame.

The tragedy in Ayotzinapa is rooted in both a long historical context and a contemporary setting of drug-related violence in Mexico. If anything about the Iguana mass-killings is surprising, its setting in the state of Guerrero certainly is not. The state of Guerrero has been plagued by extreme social inequality, poverty, and an almost total lack of political stability practically since its establishment. These systemic conditions should not be overlooked in an analysis of crime: they are often the very drivers of criminal behavior, factors that hasten the transition from being a young student to being a member of a drug cartel. Notably, on the day of the attack, the students from Ayotzinapa were on their way to gather donations for their crops and education. Dr. Carlos Illades, a Mexican historian and correspondent for Nexos magazine, describes Guerrero’s history as a series of violent cycles of social mobilization, repression by the part of the state, and creation of vigilante groups. The longstanding tradition of social mobilization is represented by the local teachers’ college, the Escuela Normal Rural Raúl Isidro Burgos, whose alumni include many famous guerrilla leaders, and which has maintained strong Marxist roots.

The school frequently came into conflict with the state government, particularly during the tenure of Governor Angel Aguirre, who resigned approximately one month after the disappearance of the students due to growing pressure from demonstrations. The federal army is often involved in repressing mobilized groups and guerrillas, as are other local authorities. When violence against the citizens of Guerrero is not perpetrated by the state apparatus, it often is by criminal organizations. Guerrero’s role as a leading producer of heroin-yielding poppies and marijuana and its strategic position in the drug trade have only served to augment the social instability of the state. Moreover, the recent break-up of the Beltran Levy cartel into clashing criminal groups further transformed Guerrero into a stage of violence and unrest. The local drug gangs in Guerrero do not seek to appropriate political power for themselves, but rather to execute several state functions, including the provenance of security and justice given the inability of the state to do so.

This was the context in which Mayor José Luis Abarca was elected in 2012. Supported by a leftist coalition of parties, the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) politician won the election by a large margin. His time in office was characterized by total opacity and nepotism of the lowest kind. Prior to the kidnappings, there were 11 members of the Abarca family employed by the state government, who were collectively receiving hundreds of thousands of pesos each month. His marriage to María de los Angeles Pineda symbolizes his link to organized crime: her father and four brothers are all members of the Guerreros Unidos cartel. The New York Times recently reported that Mexican federal officials said Guerreros Unidos regularly paid off the mayor for his cooperation and role as a cartel operative and that the municipal police acted as a muscle for both the mayor and the gang. Last year, Abarca was charged with the triple murder of leaders of local group Union Popular de Iguala. In Iguala, the collusion between organized crime and local authorities was more obvious than ever before.

As a result of their association with this family, and their role in covering up its criminal behavior, the PRD is now seen as an active participant in one of the most shameful events that Mexico has ever experienced, which has subsequently all but destroyed the myth of a modern left wing in Mexico. The centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has fared just as as badly after Ayotzinapa, as President Enrique Peña Nieto has become the face of the “Estado” which is loudly decried throughout the country. President Peña Nieto has been pushing for numerous reforms that aim to promote economic development and reintegrate Mexico into the global market. This is what his administration has called a “Mexican Moment”: a series of economic campaigns that seek to restore the government’s legitimacy and to shift the narrative from a potential failed state scenario to a rising nation. Primarily targeting the financial, telecommunications, and energy sectors, the reforms aim to present Mexico as a hub for innovation and development. Within a few months of his 2012 election, Peña Nieto was said to be “saving Mexico” in Time, and reports about Mexico started shifting from its decaying national stability to the rapid improvement in its economy. However, the administration’s late and inefficient response to the disappearances of Ayotzinapa demonstrated the illusion and failure of this policy to compensate for the ongoing violence in Mexico. The remaining political party, the right-wing National Action Party (PAN), still stands as the standard-bearers of the failed drug war and corruption. In the face of the crisis of violence in Mexico, there does not exist a political party capable of peacefully and productively expressing the frustration of Mexican society. All three of the parties have failed in the face of Ayotzinapa to provide viable and concrete political dialogue on structural changes that clearly need to be implemented in the country. There is no government discourse that responds to the magnitude of the crisis in a serious attempt to provide a viable solution to the current problems of Mexico.

In short, the police forces, the army, political parties, prosecutor’s offices, the intelligence apparatus, local governments, and the federal government are responsible, by omission or commission, for a major crime at the hands of the Mexican state. In the wake of these terrible events, reforming and rehabilitating the Mexican state is necessarily the most important goal. This rehabilitation requires, above all, justice: a clear articulation and punishment of those responsible, at all levels of the society. Neither political forces, nor state institutions, nor civil society have managed to open a public space to restore bridges to dialogue, deliberation, or proposal and development of initiatives and strategies that give a specific sense of purpose and aim for change. It is necessary to transcend fear and indignation in order to enumerate specific reforms, for this is what true justice depends on in Mexico. The huge public outcry against impunity and for the rule of law is overwhelmingly the lesson to be drawn from Ayotzinapa. Seldom has there been inserted so clearly and with such urgency on the national agenda a need for genuine reengineering of the structure of accountability throughout the country, especially in the primary levels of government. The judicial power has a great responsibility at this time to begin charging those responsible for the disappearance of the 43 students and for the countless of other murders and disappearances that preceded them – this includes the criminal gangs who perform violence as well as public officials who engineer such heinous crimes.

To enable this these reforms, dialogue is certainly important. Political leaders, political parties, and social activists have a responsibility to articulate clear and reasonable demands from the government for the sake of the mourning populace, and for the sake of their future. We have yet to see what the outcome of these rapidly spreading movements will be in Mexico, and whether they will translate into votes in future elections. If, indeed, “fue el estado,” it is now the role of the civil state to try them accordingly.