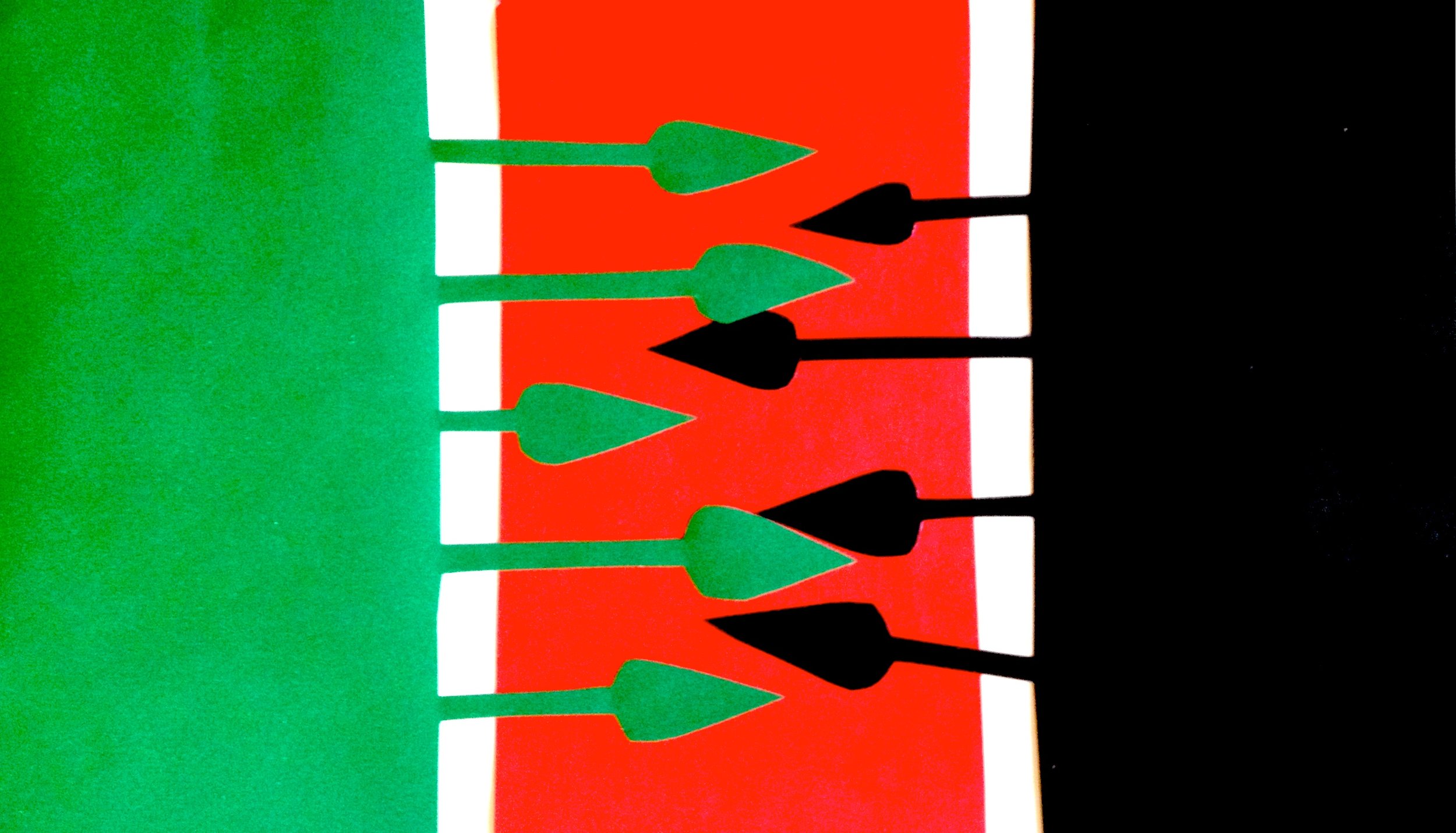

A Fatal Feud - Colonial Roots of Kenya’s 2007 Post-election Violence

Since its independence in 1963, Kenya has been hailed as an island of peace and stability within Africa. It therefore came as a surprise to the international community when violence rocked the country starting December 28, 2007, barely twenty-four hours after the conclusion of a highly contested presidential election. Since independence, Kenya had been largely peaceful, so what could have caused the 2007 post-election violence? This violence is significant because it is representative of the opinions of broader groups of people, and increasing instances of dissension post-2007 seem to have the potential to foment future violence. On December 30, 2007, the Electoral Commission of Kenya announced the results of a highly-contested presidential election. During the election, two major tribes—the Kikuyu, led by Mwai Kibaki, and the Luo, led by Raila Odinga—accused each other of electoral fraud. Immediately after the announcement of the results, Kibaki was hastily sworn into office in a secret ceremony. The ceremony aired on the state-owned television station was comical. Guests could be seen scuttling across the manicured lawns as they were hastily summoned, the state band did not play the national anthem since there was no time to call them, and the entire ceremony was over within minutes.

Violent protests, lootings, and killings rocked the country soon after. The international community intervened swiftly because they feared a recurrence of genocide, especially in the wake of the 1994 Rwandan genocide and the 2003 genocide in Darfur. Kofi Annan, then-Secretary General of the United Nations flew into the country and successfully negotiated a power-sharing deal between the two leaders. However, before the two leaders agreed to share power, more than 1,500 people were killed, nearly 600,000 were displaced, and millions of dollars in damages and lost revenue were reported.

Yet, in forcing the two leaders to sign a peace sharing deal and stop their supporters from further killings, the international community failed to acknowledge the simmering tensions that lay beneath a thin veneer of democracy. Kenya’s new democracy, after only forty-four years of independence, was too fragile and the violence was facilitated by identity politics and elite instrumentalization, all of which were legacies of colonialism.

The differences in the level of participation between the different ethnic groups emerged due to grievances that the two dominant communities held against each other. Even though Kenya has forty-two tribes, the violence was mostly between the two dominant tribes, the Kikuyu and the Luo. These two communities shared generational political dynasties that were simultaneously cooperative and competitive. While the causes of the Kenyan post-election violence cannot be attributed to a single factor, a main cause was the ethnic tensions that have been long simmering between these two dominant tribes.

Kenya’s colonial history gave rise to a form of ethnic nationalism that was accentuated by the fear that different ethnic tribes aroused in each other. These differences started with the two founding fathers: Jomo Kenyatta, who was Kikuyu, and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, a Luo, who was Kenyatta’s vice president and later, his political rival. The two dominant tribal dynasties led by Kenyatta and Oginga Odinga, distrusted and feared each other, with Oginga Odinga and his tribe feeling deprived of political leadership, while Kenyatta and his tribe feared power being taken away from them. These tensions were created by colonial legacies exploited by the tribal leaders to further attract followers. In Kenya, elite instrumentalization, where what seemed like competitive politics was in fact an insidious power struggle, was therefore paramount in rallying supporters around their strategic interests. The Kenyan masses were pawns in an elite struggle for raw state power. The two parties set groups against each other in 2007 by emphasizing post-independence political animosity and ancient hatred between their founding fathers to mobilize support among their respective followers. Kenyatta and Oginga Odinga were bitter political rivals with conflicting ideological goals. The Kikuyu felt that the presidency was theirs by right: after all, it was the Kikuyu who led the Mau Mau Rebellion that had assured Kenya’s independence. This in turn created tension among the Luo, who were excluded from political leadership. Some Kikuyu leaders used political rallies as a platform to mobilize support. The Luo in turn reacted by constructing stereotypes of the Kikuyu that characterized them as inhuman killing machines in order to justify the violence against them. However, aiding these tensions were colonial legacies that existed during Kenya’s colonial and post-colonial history.

Kenya’s colonial history gave rise to a form of ethnic nationalism that was accentuated by the fear that different ethnic tribes aroused in each other. The British colonial regime promoted ethnic discrimination to deflect anger from the colonial administration by creating the idea of “others.” When Kenya became independent in 1963, these identities took on a more sinister dimension, where instances of bias and prejudice resulted in the government giving preferential treatment to districts and peoples through the inherited indirect rule that gave tribal chiefs power. Mahmood Mamdani, the former Director of the Institute for African Studies at Columbia University, refers to this form of indirect rule as “decentralized despotism,” a form of power that excluded “others.” The main pillar of colonialism in Kenya started with a complete rebuilding of native local institutions and traditional lifestyles. Colonizers and their administrative bodies designated authority and split it into three branches, administrative, judicial and executive, in order to keep control on people in the area. Each case of resistance among the local chiefs provoked removing the tribal chiefs from office and appointing a new local authority instead. Cooperation and loyalty to the colonizers thus became the basis for incentives and rewards. The “divide and rule” policy was used as a point for contradiction and conflicts between tribes with the colonizers invoking their right to protect in order to shield some ethnic groups against others. This was effective in cementing differences between various groups. The history of colonialism shows how manipulation of “more friendly” people was used to conquer “more stubborn” people through divide-and-rule. The exploits of the British colonizers created a distinct ruling class for the convenient and proper regulations used by the colonial government to tear the indigenous communities apart. The Kikuyu elite thus became afraid of losing their power to their traditional rivals.

The Kikuyu first felt threatened when Luo members of Parliament started questioning Jomo Kenyatta’s land policies and asking for equitable distribution of Kikuyu-occupied lands. This move by the Luo legislators motivated the Kikuyu elite to maintain power in order to protect their lands. Leading the pack was Tom Mboya, a savvy Luo politician who was being groomed by the West to be Kenyatta’s successor. However, this ambition was cut short when he was assassinated by a Kikuyu hitman at the behest of the Kenyatta government on July 5, 1969. Three months after he was assassinated, ethnic animosities came to a head when Kenyatta arrived in Oginga Odinga’s home turf to officially open the New Nyanza Provincial Hospital. The local population pelted his motorcade with stones upon his arrival. Kenyatta’s security responded by shooting at the crowd and murdering hundreds of people in what is famously known as the Kisumu Massacre. In retaliation, Oginga Odinga was jailed, and since then the security dilemma has functioned as a reason to keep the fear spiraling.

Even though the Luo were not the only victims of this fear (they imprisoned vocal Kikuyu rebels like Koigi Wa Wamwere), Luos received the brunt of repressive measures enacted in the wake of these events. The measures included establishing a system of registration and surveillance, ordering expulsions, imposing special criminal penalties, financing the dreaded Mungiki sect used to suppress the Luo, excluding Luo people from important political functions, sequestering and confiscating goods, and subtly discouraging Luo residence in Kikuyu strongholds. The dominant Kikuyu elite have thus used violence as a means of coercive discipline.

The Luo, however, also had a role in the violence. They constantly clamored for a power they once held generations past. Most of the Luo felt the presidency was theirs by right, and they had temporarily “loaned” it to the Kikuyu who were now unwilling to give it back. A Kenyan is a member of a tribe first and a Kenyan second. The systematic structural and institutional exclusion of Luos from politics created a festering resentment which manifested itself as violence. The grievances that the Luo emphasized affected all facets of life. Economically, there was a disparity in levels of development because compared to the lush, fertile, and highly developed Central Province of the Kiyuku, Nyanza Province was seriously underdeveloped. This economic inequality was exacerbated by the social grievances taking the form of ethnic exclusion in terms of government jobs, and politically, the Luo became bitter about perceived chronic betrayal by the Kikuyu.

Even though Tom Mboya was assassinated in 1969, when the violence broke out in 2007, his son Lucas Mboya made the following statement: “My goal is to first get Kenyans to understand that I believe my father’s death was the point in Kenya’s history that the two most influential tribes parted, both publicly and permanently and this acrimony has been the root cause of most of the political problems Kenya has had to date.” Kenyan politics is not about policies, but about tribes, communities, and individuals. •