Denial on Trial

A hundred years ago this April 24th some 300 Ottoman Armenian intellectuals stood uneasily in the courtyard of Constantinople’s Central Prison on a calm Bosphorus night. Recovering from earlier Easter festivities, many had been soundly sleeping when abruptly summoned by Turkish authorities and transported to the prison. Unbeknownst to them, the next day would be the beginning of the end for Ottoman Armenians. The sinister plot to follow consisted of repeated episodes of Armenian communities being uprooted, exiled, and massacred. These scenes made up in brutality and efficacy what they lacked in variety–by 1918, the Armenian presence in Ottoman Turkey had been all but eliminated.

The Armenian Genocide–as these events would later be known–is a lasting source of contention between Armenians and Turks. Armenians actively remember the Meds Yeghern and some use the historical event to bolster legal claims against the successor state of Ottoman Turkey. On the other hand, the modern Turkish state actively ignores these grimmer portions of its earlier history, leveraging its substantial geopolitical clout to cloud the historical record documenting the horrific crimes that occurred within its borders. Bolstered by this state-sponsored campaign of denial, Turks and non-Turks within and outside of Turkey routinely deny the Armenian Genocide. Some European nations have enacted new laws or interpreted existing laws to criminalize denial of the Armenian Genocide. A conviction under one of these laws is currently being challenged before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Perinçek v. Switzerland, reviving the debate as to whether denial of the Armenian Genocide can and should be criminalized.

The facts of this particular case are not complicated. Doğu Perinçek, a Turkish politician, participated in several conferences in Switzerland, at which he stated that the Armenian Genocide was an “international lie.” Based upon a criminal complaint, Perinçek was found guilty of racial discrimination within the meaning of the Swiss criminal code. Perinçek subsequently appealed his conviction on the basis that it infringed upon his freedom of expression as guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights. The lower chamber of the ECHR objected to the conviction on several grounds. I will note two of the most noteworthy objections here, and leave the remaining objections to a more extensive analysis of the court’s opinion.

First, the lower chamber correctly noted that the Swiss statute in question was a broad statute that banned “discrimination...denigration or defamation” of a race, but did not single out genocide denial as a specific crime. Second, the court found in its opinion, that there was a lack of consensus on the question of whether the events of 1915 constituted a genocide. It is important to note that while the state of Turkey intervened as a third-party in the initial ECHR proceeding and presented evidence favorable to its position, Armenia was not a party initially. (Armenia has since intervened as a third-party before the case was appealed to the Grand Chamber of the ECHR.)

There exists substantial evidence against this second finding of the lower court on the Armenian Genocide. This evidence includes a wealth of primary source documentation as well as subsequent analysis, for example, the study conducted by the International Center for Transitional Justice affirming the correct usage of the term genocide as defined by the Genocide Convention. But even if a statute criminalizing Armenian Genocide denial met the lower court’s specificity standards and the court properly considered the full range of evidence available describing and classifying the Armenian Genocide, such a development would only begin a robust inquiry into whether laws criminalizing genocide denial are consistent with freedom of expression in democratic societies.

In the United States, where a wider range of speech is protected than in Europe, it is very easy to begin any discussion on freedom of speech with a presumption that speech should be protected unless it can be shown that it creates some harm to society. But this mode of analysis can prove challenging because harm is difficult to measure, and even once measured, it is difficult to weigh against the speaker’s presumed innate freedom of speech. Moreover, this approach fails to justify the protections a nation provides controversial speakers in the first place. Therefore, a more sound analysis requires a brief discussion of the theory underlying freedom of speech. After establishing this brief theoretical foundation, I will discuss how laws criminalizing Armenian Genocide denial affect the public’s memory of the historical event, and then discuss how such laws affect the development of a nation’s capacity to cogently counter future extreme speech. I will ultimately question the legitimacy and prudence of laws criminalizing genocide denial.

Advocates of criminalizing genocide denial have a persuasive argument at their disposal, especially when freedom of speech is viewed using the “classical model” of free speech. The “classical model,” as Columbia President Lee Bollinger explains in The Tolerant Society, envisions speech as a means to “arrive at as close an approximation of the truth as we can.” This argument is not new–it found its way into John Stuart Mill’s 19th century writing as well as into several prominent 20th century US Supreme Court opinions–and it carries substantial weight in the American First Amendment community of scholarship. If the ultimate goal of public discourse is to achieve truth, it is not difficult for proponents of genocide denial laws to then argue that denying proven truths adds little value to public discussion. Considering further the degree such speech can be offensive and racially provocative, one can easily fashion a rudimentary argument that the right to such speech is outweighed by its negative effects on society. This argument makes a tenuous logical leap, however, establishing a dangerous precedent, and requiring a critical assumption.

First, it equates denying proven truths that offend certain minority groups with racial hatred or even incitement. It is certainly imaginable that many who seek to stir racial hatred against Armenians also deny the Armenian Genocide, just as many neo-Nazis deny the Holocaust. But many of the Turks who deny the Armenian Genocide are victims of a biased and nationalistic educational curriculum in Turkey that is reinforced by strict speech laws. Secondly, this process of placing certain provable truths beyond the reach of debate can easily be abused by politicians seeking to dampen discussion of controversial subjects. Thirdly, this argument assumes that truth is a binary function and that once truth is determined (e.g. through an adjudication of a court), its pursuit is complete. However, the truth can exist in variety of forms. As John Stuart Mill argues in On Liberty, “collision[s] with error” invigorate the pursuit of truth. Similarly, denial of the Armenian Genocide adds life to a century-old event that is too easily forgotten by inviting affirmative speech. Said in the converse, laws criminalizing genocide denial merely suppress falsity–they do not further enunciate the truth.

This last angle of attack–that truth is invigorated by its cohabitation with error–is strengthened by the arguable assertion that the memory of past genocides,which can often serve as a catalyst for future preventative action in democratic societies, requires a particularly lively presence among a democracy’s ultimate decision-makers. Hitler’s perverse memory of the Armenian Genocide is illustrative of this point. In carrying out his exterminations some two decades later, he famously stated on the eve of his Polish invasion, “Who...speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?” Hitler was emboldened by the world’s ignorance of past genocides and similarly hoped to cover up his own genocidal schemes. While contemporaneous historians, most notably Raphael Lemkin (the creator of the term “genocide”), were aware of the atrocity through historical sources, a sufficiently robust knowledge of the Armenian Genocide did not exist among the general public and allowed Hitler to act with impunity. While substantial progress has been made in educating the public about the Armenian Genocide, the public’s memory of the genocide needs to be more salient in order to influence future policymakers. Merely relegating the official narrative to a nation’s law books is not sufficient for this task.

The benefits of lively speech are compounded by the fact that societies that actively remember the Armenian Genocide are more effective antidotes to Turkish denial than a single statute. “Person-to-person contact” is the most effective means at changing Turkey’s policy on the Armenian Genocide, explained Professor David Phillips, director of Peace-building and Human Rights Program at Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights. Unlike laws, a multitude of citizens provide a multitude of opportunities to nudge the Turkish public’s narrative towards recognition of the genocide.

While laws can articulate official state positions, Professor Phillips states that the Armenian Genocide is a “political issue” and will only be accepted if a “critical mass” forms in the general public. While extensive European discussion on the Armenian Genocide is an effective tool for conveying authentic history to the Turkish Republic, freedom of speech in Europe is also the means to transform the opinions of Turks residing in Europe. Convergence on the history requires “breathing room,” explains Phillips, in order to allow the incremental steps that will bring Turks and Armenians closer. If only unequivocal affirmation of the Armenian Genocide was allowed, moderate Turks who have not yet accepted the Armenian Genocide will be forced to withdraw from public discussion, and their opinions will remain outside the reach of effective persuasion.

Europe’s responsibility for providing the space for this dialogue is increased by the lack of a corresponding space in Turkish society. One could argue, however, that many deniers of the Armenian Genocide, like Perinçek, do not travel to Europe in order to engage in meaningful dialogue but instead aim to inflame racial tensions. Perinçek’s speech, for example, was delivered in Lausanne, the same city where the treaty ending the Ottoman-European conflict was signed, effectively reneging on previous promises of an Armenian state in eastern Anatolia. While this point is most likely well founded, there are two strong rebuttals that can be offered. First, the extreme views expressed by these individuals, at the very least, can be of value in identifying the origins of such speech. Bollinger explains in The Tolerant Society that extreme speech can serve as a “thermometer” for society seeking to diagnose and cure problematic elements. Without deniers of the Armenian genocide, it would, for example, be harder to determine the extent to which such speech is natively grown or internationally exported. Furthermore, it can help in the allocation of resources in combating extreme speech. Second, society serving as a forum for speech is not inconsistent with Europe’s longstanding role as a facilitator of diplomatic dialogue. Switzerland–a party in this case–played a leading role in facilitating dialogue between Armenians and Turks in the first decade of the 21st century and helped lay the foundation for the groundbreaking, though contested (and now defunct), Armenian-Turkish Protocols. However, Switzerland has seemingly exchanged its role as a bold facilitator of dialogue to a mild suppressor of speech. While this possibly casts doubt on the sincerity of the Swiss reconciliation efforts, it could also explain why a nation whose peace efforts were subjected to torturous political maneuverings, particularly in Ankara, has taken this step back from the role of a facilitator of dialogue.

It is important to emphasize that the opening of space for dialogue in Europe does not absolve Turkey of its abysmal free speech record; hopefully the former will facilitate the latter. Turkey’s pursuit of the current case before the ECHR is somewhat laughable considering that it was ranked 154th nations for press freedom by Reporters Without Borders in 2013. Professor Phillips explains, if Turkey was serious about freedom of speech it would stop jailing people who speak out on the Armenian Genocide under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code. Phillips further explains that Turkey could unilaterally open its border with Armenia in order to directly facilitate dialogue with Armenians. Even if President Erdoğan of Turkey lacked the political vision for such an undertaking, the free interactions Turks have in Europe and bring back to Turkey will only add pressure on the Turkish government from within. While Erdoğan firmly denies the Armenian Genocide, Phillips believes that President Erdogan’s impressive “bravado” fundamentally comes from a position of insecurity. While possibly resistant to external pressure, he is not immune from the tension growing under his rule.

The preceding discussion offers an argument for why European laws suppressing genocide denial harm the memories they aim to protect as well as the societies that the victims and perpetrators come from. However, the benefits of extreme speech extend beyond the narrative it hopes to discredit and the communities it angers, and helps strengthen the tools European nations employ to combat future extreme speech at home. Societies have two primary tools for combating extreme speech directed towards minorities: directly outlawing the speech or employing firm counter-speech which simultaneously discredits the extreme speech while supporting the victims of such discourse. Simply outlawing extreme speech–such as genocide denial–reduces the necessity to produce counter-speech and allows this critical societal aspect to atrophy. Consider how societies respond to murder. The vast majority of murders, while horrific, get less than three minutes on the nightly news.

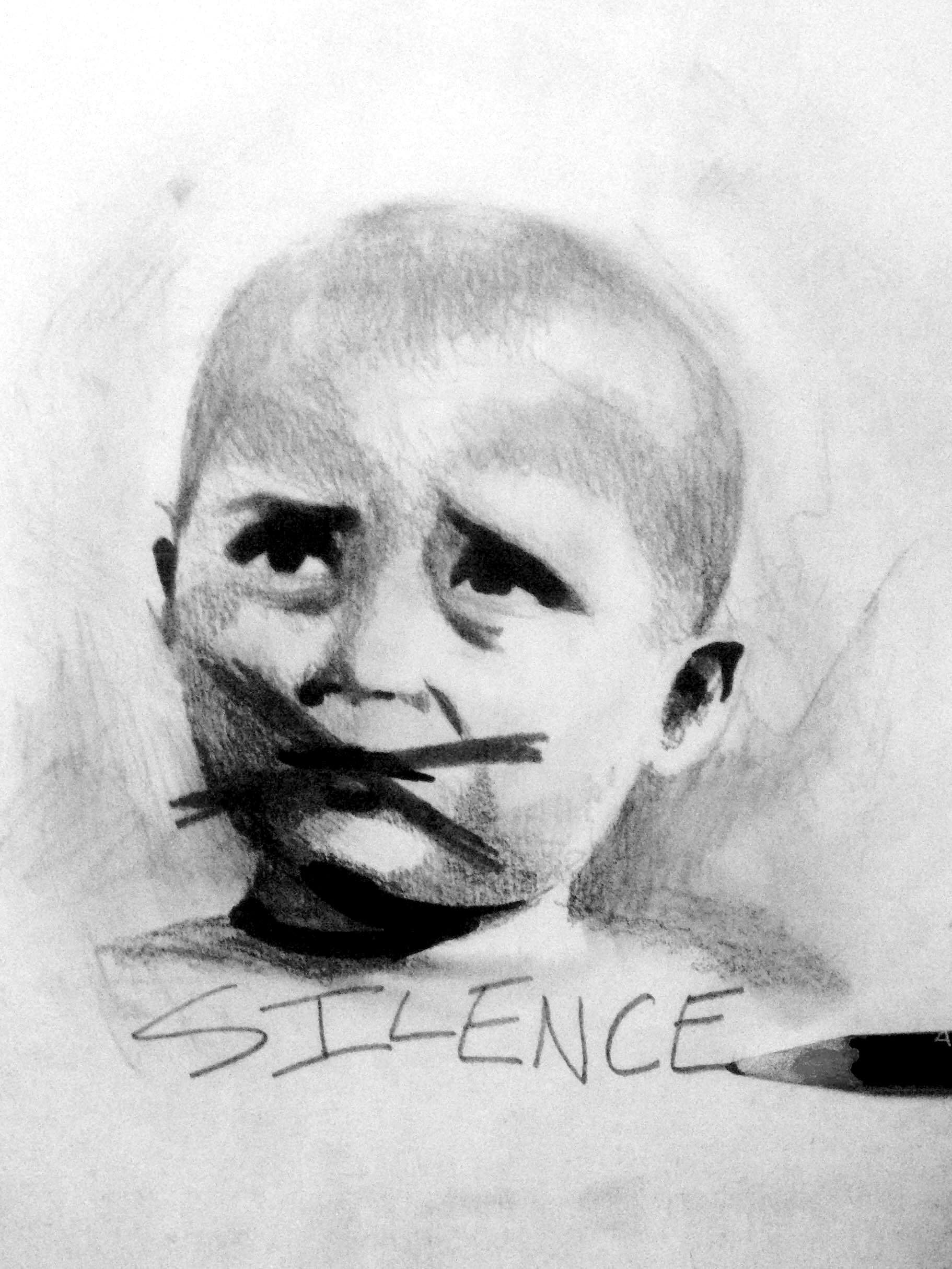

Societies do not condemn these individual acts (which are arguably graver than the majority of hate speech) because they know the perpetrators will face institutionalized justice. Similarly, placing the responsibility of rejecting genocide denial in the hands of judges removes the burden from civil society, and accordingly allows its voice to grow mute.

Suppressing genocide denial does not merely inhibit an alternative means of responding to extreme speech; it also inhibits the more effective means of countering extreme speech. This is not an obvious statement, for there are strong arguments in favor of legal remedies over counter-speech. The state is the pinnacle of power in a society and has a vast amount of coercive means at its disposal to influence behavior. Furthermore, legal institutions in a functioning democratic society could be considered more impartial than various elements of civil society and provide a consistent process for adjudicating abuses. But a robust civil society can offer an effective response to extremist speech. The firmness of counter-speech can be seen in the example of Holocaust denial in America. While not outlawed, such speech is so strongly objected to that it can end careers and spur instantaneous apologies.

Counter-speech is also preferential because it utilizes many more elements of society than a single judge and makes the speaker’s isolation in their extreme opinions all the more apparent. Furthermore, societal responses to extreme speech do not give a preferred victim status to extreme speakers, unlike laws criminalizing extreme speech. Such a mantel gives the speaker a sense of righteousness that gives their extreme speech more legitimacy. Societal counter-speech also provides a more nuanced approach to extreme speech, allowing societies to provide a greater range of responses than the punishments dealt out by a court. Societal counter-discourse also can quickly adapt to rapidly changing speech in a variety of changing circumstances. Most importantly, a strong societal response, more so than a judge, is capable of responding to extreme speech while offering solidarity with alienated minority groups. This societal capacity is critical for a European community currently wrestling with the consequences of deep ethnic and religious tensions.The consequences of not developing the capacity for counter-discourse cannot be more apparent in Europe. Currently, Europe has seen a wave of violence against media outlets by individuals who claim they are avenging blasphemous speech, perhaps most notably the attack on Charlie Hebdo on January 7, 2015. Attacks on media outlets shine a spotlight on the issue of how to respond to possibly offensive speech that is somewhat pertinent to public discussion and does not pose an immediate threat to public order. On one hand, silencing the speaker limits their ability to offer social commentary. On the other hand, permitting such speech allows for religious and ethnic minorities to be subjected to offensive speech that can lead to feelings of marginalization. This question has no easy answer, and I do not attempt to provide one. However, robust societal counter-speech is part of the solution. Without repeating the aforementioned arguments for why such speech is advantageous, there is an added benefit of having societies counter offensive speech that cuts across ethnic or religious lines. Counter-speech puts aggrieved parties in contact—albeit heated contact—and that can serve as a basis for future discourse instead of allowing animosities to seethe in silence. Despite the dissonance that ensues from such speech, real conversations can arise from the smoldering remnants of these tirades and tantrums.

The issue of criminalizing denial of the Armenian Genocide is not solely pertinent to two feuding communities, but to the European community as a whole. The predicted benefits of free speech, which often exists solely in the form of academic conjecture, take the form of political potential. This issue also illustrates how speech ironically can simultaneously scar and bind discussants together, including the speakers and the society as a whole. Moreover, the role of countering extreme speech can help mobilize larger societies that may too easily place extreme speech directed towards minorities in its peripheral vision. In this regard, allowing extreme speech strengthens a much needed capacity of society. It is understandable for the descendants of victims to question why they should endure offensive speech to aid the progress of the societies they live in. But looking back from a century on, it may be a small price to pay for a better society for all.