Charge of the Right Brigade

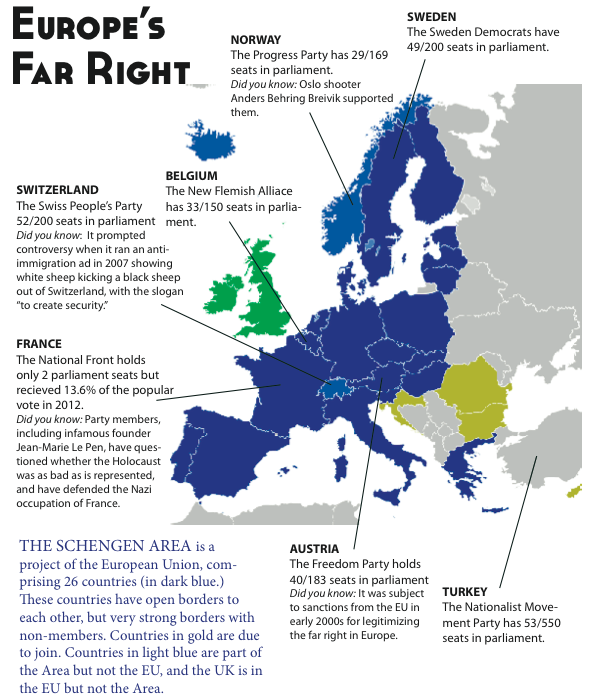

European countries have traditionally had political parties that range from the very liberal to the very conservative, stretching further in both directions than, say, the two political parties in the United States. Historically, the more conservative parties remained firmly on the fringes of society and did not gained much power politically. The recent changes in the ethnic distribution of European population, mainly due to a massive influx of immigration, have popularized the furthest-right parties, most of which have an aggressive anti-immigration stance.

The Schengen Area currently encompasses twenty-six European countries that do not require documentation for travelers to pass between them. When it was established during the 1980s, only ten countries were party to the agreement, but since then, it has grown significantly, especially since the establishment of the European Union. This agreement was an embodiment of the attitude emerging in Europe during this time: immigration was tiered, with immigrants from fellow European countries being perceived as more desirable than immigrants from non-European countries.

In 2014, the majority of non-European residents in European countries originated from Turkey, with over 1.98 million immigrants, and from Morocco with 1.38 million immigrants. Both countries have predominantly Muslim populations: 99.8% of Turkey’s population is registered as Muslim, and 99% of Morocco’s population self-identify as Muslim. Thus immigrants from non-European countries, already traditionally stigmatized in society, are predominantly Muslim. They tend to live in poorer neighborhoods with a higher crime rate, and thus gain a negative reputation among non-immigrant Europeans. Even the children of immigrants are subject to the same discrimination and marginalization.

Recently, a series of terrorist attacks, most notably the shooting rampage at the Charlie Hebdo publishing office in Paris on January 7, and threats throughout Europe, attributed to radicalized Islam, have contributed significantly to anti-Muslim sentiment throughout the more right-leaning European political parties. This shift has disturbed the political balance of many European countries and empowered their right-wing parties, with the possibilities for several long-reaching political repercussions, which differ by specific country. Specifically, we can look to France, a country with one of the highest populations in Europe.

France has been the European country most radically affected by the surge in anti-Muslim sentiment, primarily due to the attacks against Charlie Hebdo which occurred in the heart of Paris. François Hollande, the French president, has up until now been largely unpopular and regarded as a weak leader: before the attacks in Paris, his approval rating was at nineteen percent, but after his reaction to the attacks, it rose to forty percent. Some of that increase can be attributed to the inevitable increase in patriotism and solidarity after attacks of that nature, but Hollande’s heightened visibility at the scene of the attacks and his willingness to unite political parties in a show of opposition to the attacks was very well received by the French people.

After the attack at Charlie Hebdo, the French left embraced patriotism in a way that is typically unusual for the more liberal French parties. The French flag was omnipresent during memorials and rallies, and the tragedy provided a bridge between political parties. One of the more salient ways in which the French political parties joined in solidarity with international leaders was through a rally in which French and world leaders marched against terrorism and in honor of the victims of the shooting.

Marine Le Pen, however, the leader of the National Front Party, was one of the few leaders who was notably not invited to the rally. She has long espoused anti-Islamist rhetoric on behalf of her far-right party, and has thus enjoyed limited political success as many French voters find her too extreme. In an interview with the BBC, she made a now notorious comparison of Muslims praying on the streets of Paris to Nazis occupying France, terming them both an illegal occupation. Le Pen denies accusations that she is an Islamophobe or a racist, but nonetheless contends that France needs to drastically reduce immigration. In February 2015, she cited figures that France currently receives two hundred thousand immigrants a year, and she seeks to reduce that number to ten thousand a year. She justified her position by claiming that six million people in France are unemployed, while ten million live in poverty, and wondered the following about immigrants: “Do we just put them in ghettoes or particular neighborhoods where we’re basically handing them over to gangs or the mafia?” Le Pen directly linked, in her reasoning, the high immigration levels to immigrants living in poverty, which she in turn linked to a heightened crime rate. Not only does she advocate the drastic curtailment of immigration, she also suggests a policy in which France deport foreign nationals who are unemployed or who are found guilty of a crime.

Le Pen appeals particularly to rural French voters, and she took advantage of that base after the shooting by touring “la France profonde,” or “the real France,” after she was not invited to the rally that Hollande held with other world leaders in Paris. She rallied instead in Beaucaire, a small city in the south of France in which her party had historically been successful in elections. She and the other members of the National Front Party criticized Paris for being where the corruption in the country originated, and thus it was particularly fitting for her to rally instead in the French rural areas.

In the presidential elections, Marine Le Pen and other members of the National Front Party have secured a proportion of the votes, but they have so far not been successful on a national scale. In polling before the shooting, Le Pen showed an unprecedented lead in the 2017 presidential elections, with approval ratings between twenty-eight and thirty percent, depending on the other candidates in the election. In the same polls, Hollande’s projections were between sixteen and seventeen percent. Although his approval ratings have increased since the shooting, they are not expected to remain at the same levels, since the increase was mainly a product of his strong, patriotic response to it, one which he is already shying away from.

If the 2017 elections were held today, Marine Le Pen would be the next French president, and the National Front Party would come to greater power than it has ever wielded before. Le Pen is certainly not the most radical member of her party, and is instead one of the most electable ones in that she is more leftist than many of her National Front colleagues. Aymeric Chauprade, a member of the European Parliament for the National Front Party, was filmed alleging that “France is at war against Muslims.” Even Le Pen took issue with his statements and publicly distanced herself from them, being sure to point only to radical Islam as a problem for France, a point that seems disingenuous given her likening of Muslims peaceably praying on the streets of Paris to the Nazi occupation of France, however. No matter how much Le Pen tries to moderate her views in preparation for a national presidential race, her victory would be not just for her, but also for her whole party, and the political discourse would shift drastically to the xenophobic right.

France, like many other European economies, has recently been under significant pressure, especially from the countries in the European Union that are requiring bailouts from their economic partners. As these other countries weaken the Euro, the more traditionally prosperous European countries suffer economically. As Professor Robert Jervis of the Columbia University Political Science department told CPR, the European Union has for a time been in “economic distress.” In France, for example, the unemployment rate has been steadily rising since 2008, when it was at 7.2 percent, and as of November 2014 it was at 10.5 percent, almost twice that of the United States at the same time. This high unemployment rate recalls Le Pen’s proposed strategy of deporting all foreign nationals who are unemployed in a bid to improve the economy and lower the unemployment rate.

Le Pen claims that along with an economic danger, Muslim immigration also presents a threat both to national and world security, and to the very foundations of French culture. The attack at Charlie Hebdo seems to support her argument as Le Pen alleged that Europe, and especially France, has been unwilling to recognize publicly the dangers of Islam because of “political correctness and fear,” even though “behind terrorism is only a means of Islamic fundamentalism [and] behind terrorism is an ideology which developed in our land, in our cities and the rest of the world.” Le Pen alleged that the movement was in some part developed in France, and thus she claims that France has a responsibility to put an end to it.

The attack at Charlie Hebdo was ostensibly a fundamentalist Muslim attempt to attack the freedom of speech that allowed the magazine to publish images of Prophet Muhammad’s face. This is a freedom of speech that Le Pen cites as being a basic tenet of democracy and a value that French culture holds very dear. When Marine Le Pen was invited to speak at the Oxford Union, students outside protested her vocally, calling her a “fascist,” a “racist,” and “Islamophobic.” Le Pen countered by saying: “I am deeply attached to the notion of democracy but I am not sure they are, because my freedom of speech, in fact, freedom of speech, is one of the great values that we must uphold.” She said this in reference to students who opposed her invitation to the Oxford Union, but her thinking also contains a wider message: democracy rests on freedom of speech, and any who oppose it are opposed to a democratic government. This is a particularly resonant message after the attack on Charlie Hebdo, which was targeted for exercising its freedom of speech with a radical message.

By arguing that other political leaders are not willing to condemn radical Islam because of “political correctness and fear,” Le Pen astutely depicts herself as the politician who can preserve the rights and safety of the French people from the cowardice of the politicians in Paris.

She appeals to the French suburban people and seeing as she was not invited to the massive rally President Hollande organized in Paris, she furthered her image as the politician of the people. Her image is of one who will stand for the best interests of France, and will not be cowed by requirements of political correctness. In May 2014, Le Pen claimed that the National Front Party’s “objective is to block all ideas and projects that are anti-Europe and against our objectives.” She declared her party “the representatives of France [who will] defend France and tell [the French people] the things as they are.” Through her rhetoric, Le Pen implied that voting for her is a simple act of patriotism, since her party stands for the rights of the French people.

She still, however, counters all claims that European Muslims are being scapegoated, and instead claims that all measures she proposes are solely for economic purposes, and that she holds no bias against the Islamic faith or its devotees. Anti-Muslim sentiment, which she exploits, is nonetheless palpable throughout Europe and in rhetoric emerging from Le Pen’s party, and the massive spread of ISIS has contributed to that. There is a hysteria as ISIS fighters spread videos of increasingly brutal murders and as they take over even more land. Stories of brutalities within ISIS-controlled territories spread, along with tales of Europeans, some as young as schoolchildren, traveling to join the Islamic State.

Anti-Muslim sentiment has spread for years throughout the more conservative political movements of Europe, and the recent rash of terrorist shootings in France and Denmark, along with the mass reporting of the brutality of ISIS, has brought these sentiments to international attention. The emergence and popularization of these movements is a troubling sign for Europe, in which millions of Muslim immigrants live. It is especially concerning when politicians disguise their speech as not being xenophobic or racist, but rather as being solely about economics or indisputable fact. When Le Pen argues that it would be better for the economy to deport thousands of Muslim immigrants, she is bolstering her argument in a way that appeals to a wider audience than just those who admit they are biased against Muslim immigrants. Giving her argument alarming mainstream traction that insinuates it into moderate political dialogue.

The developments in the far-right political movements in Europe, particularly the National Front Party in France, are changing every day, and thus it is difficult to make predictions about what will occur in the coming months. It is undeniable that terrorist attacks and the increasingly high-profile violence wrought by ISIS have a significant effect on increasing the anti-Muslim sentiment felt throughout these parties, but millions of moderate Muslims around the world have condemned these extremist attacks and even died fighting against them, and yet the religion as a whole continues to be widely vilified.

What it is possible to say more definitively, however, is that these far-right movements pose a danger not just to Muslims, but also to all of democratic society. Marine Le Pen is right when she says that freedom of speech is a tenet of democracy, and she is certainly entitled to exercise her right to it. What she neglects to mention, however, is that democracy also hinges on a freedom of religion, and that denying that freedom is just as deadly as denying the freedom of speech. Moderate Muslims around the world are judged as belonging to a religion that has become so perverted by fundamentalism and radicalism as to be unrecognizable from the moderate faith they practice, and they are forced to defend their beliefs. This is not a fight against Islam or Muslims, but rather a fight against hate and its violent potential, whether that hate is presented as Islamic fundamentalism or as xenophobic political movements.•