Briefing: Handling Growing Energy Consumption

By 2030, global population is projected to increase by 1.3 billion people, and global income, in real terms, is projected to roughly double. With increased wealth and population comes increased consumption—of cars, refrigerators, televisions, air-conditioning, and air travel. For example, the number of automobiles is on course to double by 2035, to 1.7 billion worldwide.

By 2030, global population is projected to increase by 1.3 billion people, and global income, in real terms, is projected to roughly double. With increased wealth and population comes increased consumption—of cars, refrigerators, televisions, air-conditioning, and air travel. For example, the number of automobiles is on course to double by 2035, to 1.7 billion worldwide.

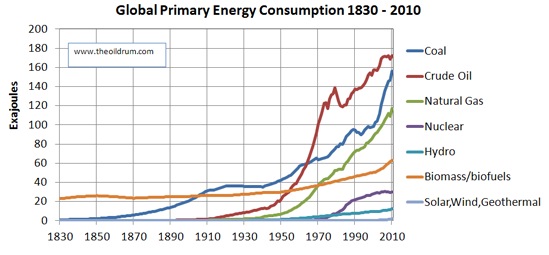

With greater consumption comes greater energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. Assuming current policy continues unchanged, the International Energy Agency projects global energy use will double by 2050, and greenhouse gas emissions will rise alongside growing energy demand.

To be clear: Increased energy use can be a good thing. Access to affordable and reliable energy is a necessary condition to reduce poverty, improve public health, and increase economic growth. Modern energy services can pull people out of poverty and improve living conditions in myriad ways, boosting productivity and efficiency in everything from agriculture to medicine to transportation to telecommunications.

Today, 1.3 billion people do not have access to access to electricity, and 2.6 billion do not have access to clean cooking facilities. These people are mainly in developing Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Just ten countries account for two-thirds of the population without access to electricity; India alone accounts for one-quarter. Billions of people are burning firewood, coal, dung, charcoal, and diesel for generators. These fuels are bad for human health and the environment.

The challenge is to expand access to affordable and reliable energy sources, and to do so without unduly harming the planet. It will be a long time until renewable energy alone can power the global economy. Renewables are projected to be by far the fastest growing form of global energy in the decades ahead—and yet fossil fuels are still projected to generate three-quarters of the world’s energy in 2035. Individual countries and the global community should take steps to speed the growth rate of renewable energy, but fossil fuels will need to be part of the mix for years to come.

So what should policy makers do to promote economic growth and development, facilitate access to affordable and reliable energy supplies, and also encourage a transition to a lower carbon economy.

First, new technologies have made it possible to dramatically increase production of natural gas, which is cleaner and emits less carbon than both oil and coal. Natural gas has the potential to displace the use of those fuels, reduce the growth rate of greenhouse gas emissions, and buy some time until lower carbon and zero-carbon forms of energy become more economical.

Second, the United States and its allies need to engage in energy diplomacy to help countries bring new supplies online that can help stabilize markets, lower prices, and provide a strong foundation for economic growth. Iraq, for example, has the potential to double its oil production by 2020 but is facing the prospect of internal conflict for reasons including disputes between the north and south over control of oil production and revenue. The United States can play a key role in helping to manage such disputes and encourage safe and responsible resource development.

Third, US policy makers should engage with developing countries that are poised to reap new energy resource windfalls to encourage reforms that allow the new wealth to benefit all the country’s people, avoiding the “resource curse” trap that has befallen so many others. These include building political institutions, good governance, transparent finances, and effective laws and regulations.

Fourth, the United States should promote regulatory, legal and structural reforms that create incentives for investment in electrification in developing countries. This includes investment in the underlying pipeline and transmission grid infrastructure that will provide people access to the country’s resources. Mozambique, for example, may soon see large offshore gas production, but without domestic pipeline investments, that gas will be exported on ships rather than used to provide electricity to the people.

Finally, energy efficiency is often the most cost-effective way to reduce energy demand, prices, and emissions. According to the IEA, two-thirds of economically viable energy efficiency opportunities will remain unrealized through 2035. Governments should deploy more finance mechanisms for efficiency investments, set defaults that address behavioral biases that lead people to ignore opportunities to save energy and money, and promote regulatory changes that allow investors to reap an appropriate share of the rewards of efficiency.

By taking steps to get it right, the world can increase global energy production and provide affordable and reliable energy supplies that help pull millions more people around the world out of poverty—while also accelerating the transition to cleaner and more sustainable forms of energy.