The Ultimate Gamble

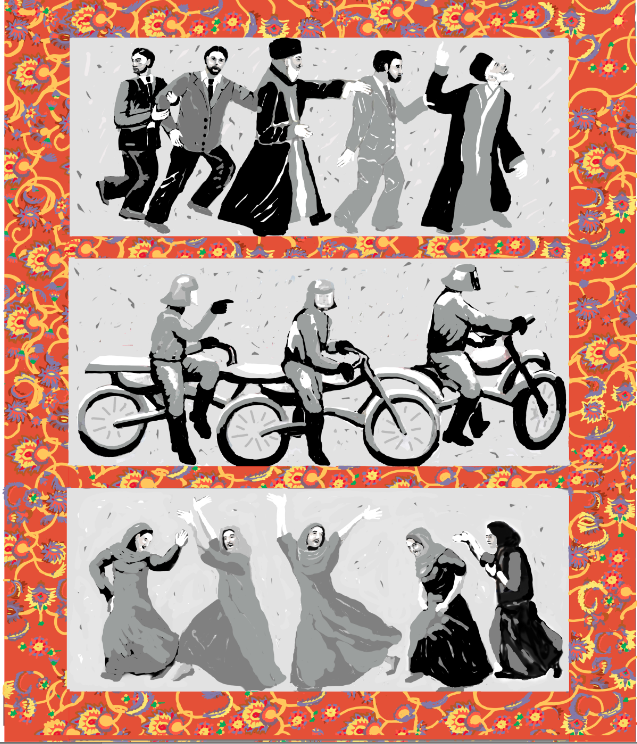

In June of 2013, Iran will elect a successor to its two-term president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. It will be the first presidential election to take place since the Green Revolution of 2009, the scene of mass protests in response to the direct manipulation of Iranian electoral outcomes. As they gained momentum, the protesters were brutally suppressed by Iran’s security forces. Establishment forces in Iran, represented by the then-close relationship between President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, used the country’s security infrastructure to crush dissenting reformist parties and their supporters. At the street level, Basij militiamen were deployed on dirt bikes to break up protests, and paramilitary forces fired on protestors. The troubling events were chronicled in countless videos posted on YouTube and broadcasted worldwide. By some estimates, as many as 72 protestors were killed, with 4000 protestors at least temporarily imprisoned.

In June of 2013, Iran will elect a successor to its two-term president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. It will be the first presidential election to take place since the Green Revolution of 2009, the scene of mass protests in response to the direct manipulation of Iranian electoral outcomes. As they gained momentum, the protesters were brutally suppressed by Iran’s security forces. Establishment forces in Iran, represented by the then-close relationship between President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, used the country’s security infrastructure to crush dissenting reformist parties and their supporters. At the street level, Basij militiamen were deployed on dirt bikes to break up protests, and paramilitary forces fired on protestors. The troubling events were chronicled in countless videos posted on YouTube and broadcasted worldwide. By some estimates, as many as 72 protestors were killed, with 4000 protestors at least temporarily imprisoned.

While this swift crackdown was successful in keeping Ahmadinejad in power, it had serious ramifications for his once strong relationship with Khamenei. The violence against the Iranian people undermined the credibility of the Supreme Leader as the nation’s self-professed guardian. As a result, Ahmadinejad and his allies have since sought to distance themselves from the Islamic leadership, triggering an internal power struggle. Many observers have gone so far as to argue that the post-election violence marked the end of the strong democratic principles of the Islamic Revolution, and signaled the emergence of a dictatorial “Imamate,” which exercised its power by overtly authoritarian means, wielding the security apparatus of the state to force political outcomes.

This purported transition is indicative of a larger trend. Over the past decade, Iran’s national security strategies have become its defining characteristic, to such a degree that considerations of domestic politics are inextricably linked with functions of national security. On one hand, the country’s nuclear program, its hostility toward Israel and the United States, its support of organizations engaged in terrorism and the Syrian regime, and its aspirations for regional hegemony have all served to isolate Iran from the international community. On the other hand, in the domestic sphere, the Iranian people are reeling from the effects of a robust sanctions program, as inflation and unemployment strangle the economy. Taken together, these two effects of the current national security policy – international condemnation and domestic unrest – have exacerbated Iran’s longstanding internal power struggles.

Since the 2009 fallout, Iran’s current president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and his cadre of Osulgarayan (or Principlists) have been vying for political survival against the clerical establishment led by Khamenei. Given the links between Iran’s national security policies and its domestic economic and political environment, influence over entities such as the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (VEVAK) will prove crucial to the victory of the Principlist faction in the political arena. Therefore, understanding Iran’s national security strategy from the Principlist standpoint offers insights into the potential outcomes of the forthcoming presidential election.

Iran’s national security policy is formulated in response to three primary concerns. First, Iran’s geographical position leaves it prone to numerous strategic threats. Second, the country’s ethnic minorities are concentrated in border regions, putting the cohesion of the state at risk. Third, Iran’s economy is poorly managed, and has serious structural challenges. According to the analysis of Ray Takeyh, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a former State Department official, these three concerns can be transposed into three “circles” of national security activity. The first circle is the strategically crucial Persian Gulf, without access to which Iran, unable to export crucial oil and gas products, would experience an economic catastrophe. The second circle is the Arab East, encompassing the critical Arab-Israeli conflict. The final circle is Eurasia, which includes the chronically unstable Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as a historically interventionist Russia and a resurgent Turkey. In response to three major national security threats, manifested in three separate regions of concern, Iran has historically tended towards measured pragmatism in its national security policy. And yet, “the intriguing aspect of Iran's policy is that it can be both dogmatic and flexible at the same time,” according to Takeyh. “The tensions between Iran's ideals and interests, between its aspirations and limits, will continue to produce a foreign policy that is often inconsistent and contradictory.” The inconsistencies in Iranian national security policy seem to be multiplying.

In 2005, when Ahmadinejad came to power, Iran’s national security outlook was precarious. There was a legitimate concern throughout the theocratic regime that the United States might choose to do in Iran what it had recently done in Iraq. According to Michael Dodson and Manochehr Dorraj, Ahmadinejad was critical of Khatami's moderate policies that had "no tangible benefits" in the face of the new and significant vulnerability to US attack. As Dodson and Dorraj conclude, “For Iran’s clerical elite, the need for a nuclear deterrent to a potential US or Israeli attack increased.” From this moment, the geopolitical aspect of Iran’s national security paradigm took precedent. Upon election, Ahmadinejad restarted Iran’s nuclear program (with the outward narrative that the program was for civilian energy purposes), and began to employ a more confrontational, hegemonic rhetoric, couched in the language of a populist and anti-imperialist foreign policy, buoyed by the economic boon of record oil prices.

In reality, the rhetoric outweighed the military threat posed by Iran to the United States. As Kaveh Ehsani, a professor at DePaul University, attests, Iran’s “conventional military capabilities are those of a third or even a fourth-rate power, unable to threaten its much smaller neighbors, let alone the US military.” While under the rule of the Shah, Iran had amassed a world-class arsenal, the Iran-Iraq war and the subsequent freeze from American and European arms markets crippled its capabilities. Iran’s rhetoric has been hawkish, in no small part due to Ahmadinejad’s famed bombast, but the overall outlook of the military doctrine has been primarily defensive. Unable to match its neighbors in conventional forces, the pursuit of a nuclear deterrent is understandable. Moreover, Israel and Pakistan, both historic enemies of Iran, wield significant nuclear arsenals. For Iran to preserve its stature in the region, nuclear proliferation was seen as necessary.

In the intervening years, the international community has strongly condemned Iran’s nuclear program. Questions surrounding the survival of the Islamic Republic have recently acquired a new urgency as the prospects of a US-Israeli military strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities loom over the region. But the potential damage of a military strike pales in comparison with the sustained effects of the sanctions program. The Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 – which expanded the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act of 1996 – and similar pieces of American and international legislation, have combined a trade embargo with targeted financial sanctions to increase the cost of Iran’s non-cooperation. The United States has successfully lobbied the European Union, Japan, and other key nations to reduce their reliance on Iranian oil, the price of which had already precipitously fallen since Ahmadinejad’s 2005 election. Moreover, Iran’s banks, including the central bank, are prevented from conducting vital international transactions. Meanwhile, the IRGC has capitalized on the collapse of the private sector to work with major Iranian industries, including oil and gas, construction, transportation, and telecommunications, earning the resentment of the Iranian populace. Without a significant improvement to Iran’s economic outlook on the horizon, the country remains ripe for popular unrest.

Some Iran analysts have suggested that the Islamic Government is “unraveling,” and that the extreme national security and foreign policy positions being taken are a reflection of the degraded decision-making capacity of the Islamic Republic. This unraveling finds its roots in the wake of the 2009 presidential election. As Jamsheed Choksy, a professor of Eurasian studies at Indiana University, notes, for the Principlists and the clerics, who conspired together to award a second term to Ahmadinejad in the face of the Green Revolution, “it soon became clear how narrow the Islamic Republic’s victory over the Iranian people actually was, and how brittle the regime had become in the process.” The trauma of 2009 splintered the relationship of convenience between Ahmadinejad and Khamenei. For Khamenei, so brashly confirming Ahmadinejad as president in the aftermath of the disputed election was a costly move. Choksy writes that while Khamenei expected that Ahmadinejad “would become ever more beholden and subservient,” the second term president instead would instead rebel “against his clerical patron” with his cadre exhibiting “increased autonomy form the theocrats in both domestic and foreign affairs.” In the wake of this new discord, “branches of the state continue to attempt to wrest power for themselves.”

Both Ahmadinejad and Khamenei have sought to align these various branches into their respective camps. Importantly, the only institutions in the Iranian government that are engaged in the active mitigation of internal political threats are the national security entities. The Revolutionary Guard, which is constitutionally mandated to protect the Islamic system in Iran, controls large swathes of the economy, funneling rents to the government in lieu of dependence on (or accountability to) civil society. The Basij militia and the Ministry of Intelligence suppress internal dissent and eliminate political enemies at street-level and in cyberspace. For the Principlists, influence over these bodies has been a primary goal since the Green Revolution exposed weaknesses among the clerical establishment. In an environment where elections can be easily manipulated, the exercise of force may be judged the best guarantor of outcomes.

With their political survival at stake, the Principlists, guided by Ahmadinejad’s astute chief of staff, Esfandiar Rahim-Mashaei, have managed to win over the support of both the IRGC and the National Security Council. In an unusual staffing move, Ahmadinejad selected just one cleric for his cabinet, Heydar Moslehi, who also conveniently currently serves as the Minister of Intelligence and National Security. Moslehi’s allegiances have generally belonged to the armed forces and not to the theocracy.

Moreover, Choksy notes that in exchange for the leeway to “steadily [take] over every major industrial sector” within the country, especially as Iran’s economy turns inward under the pressures of international sanctions, Ahmadinejad has been able to entice the IRGC and the related Basij militia to aid in centralizing power within the executive office of the presidency. The significance of this power grab is hard to understate, and if fully realized would amount to something akin to a de facto coup. In the establishment of the Islamic Republic, the position of the Supreme Leader was expressly designed to derive its strength from the direct control of major elements of the national security apparatus – a kind of ultimate head of state. That the current situation represents such a reversal of this original intent reflects the very tenacity of the Principlists. As Aaron Menenberg of Syracuse University summarily states, “The president and his protégés have successfully attempted to take advantage of the hardliners unpopularity to tilt the balance of power in their favor” in mobilizing what has been called the “Principlist-Militarist Complex.”

The Principlists seem to have found a potential means for survival in this newfound capacity to influence national security policy, but it may require them to sacrifice the golden calf of the nuclear program in order to regain the support of the international community and salvage the economy. In order to do so, the Principlists will have to renegotiate their ties with three main bodies in Iran’s governmental structure: the office of the Supreme Leader and the clerical establishment, the IRGC, and the electorate. With the next presidential election on the horizon, navigating the change in leadership from the polarizing Ahmadinejad will be key. Rahim-Mashaei, Ahmadinejad’s likely successor as the Principlist candidate, is known to hold notably liberal views – a sharp distinction from the hard-line politics of 2009. In fact, Mashaei has vocalized an alternative vision for the governance structure of Iran. In criticizing the clerical establishment, he has stated, “An Islamic government is not capable of running a vast and populous country like Iran.” While Mashaei does not advocate the dissolution of the Islamic Republic, he certainly argues that the powers of government must lie in elected offices of the presidency and the legislature as informed by “pragmatic values” – a brewing paradigm shift that does much to discount ties to the unpopular clerical establishment.

Next, the Principlists will have to undertake the delicate task of redefining the role of the IRGC and the security infrastructure. The evidence is clear that the Revolutionary Guard benefits from Iran’s economic isolation. A return to normal economic activity would entail a disruption of the clientelism that has kept the IRGC manageable. More over, any détente with the international community will require some marginalization of the IRGC’s role in national security strategy, most notably through the termination of the nuclear weapons program. Convincing the leadership of the Corps to allow such a restructuring will require careful negotiation. Crucially, though, as the Principlists will no doubt argue, should tensions over the nuclear program continue to escalate, provoking a military response from the international community, the IRGC would likely suffer a humiliating defeat. Given a choice between retaining at least some of their present stature and suffering a rout, the generals will likely choose to acquiesce.

Finally, the Principlists must seek to earn back the trust of the populace by aligning national security policy with a pragmatic focus on economic development. There is a large body of evidence to support that the Iranian electorate would welcome a rapprochement with the West, with some surveys showing more than 70 percent popular support for such initiatives. Moreover, Ahmadinejad’s waning popularity is a direct result of the degradation of his populist appeal as the domestic economy weakens. Righting this decline, even with a similar populist narrative, would likely earn the Principlists the support they need. Furthermore, in Choksy’s assessment, Mashaei has been shown to be an agreeable candidate to “intellectuals, artists, entrepreneurs, and the youth,” who underpin the core of Iranian civil society. While the Principlists may not be the reformist party that democratic activists have sought, they seem willing to explore nuanced reformulations of key policies and a piecemeal approach to forge a path to political supremacy. Despite this potential, the recent parliamentary elections were seen as a victory for the supporters of the Supreme Leader, with Principlist candidates largely excluded from ballots. It may be the case that the Principlists are biding their time and hedging their bets on the presidential elections, which have a far greater significance, especially from the standpoint of national security strategy. Rather than having expended their limited political capital to pressure the clerical Guardian Council to accept its parliamentary candidates, the Principlists will likely make a major push for the presidency, where any interference such as a denied candidate or electoral fraud could be quickly converted into a flashpoint around which to mobilize the public and security apparatus in open political conflict.

With Mashaei as the presidential candidate, the Principlists may be able to execute these moderating goals and earn lasting political credibility. However, in the face of concerted political opposition from the clerical establishment, the outcome of the forthcoming presidential election is far from guaranteed. Should the power struggle manifest itself in the form of electoral abuses, as happened in the recent parliamentary elections, we might expect mass demonstrations similar to those in 2009. Even if a 2009-style, pro-democracy movement of liberally minded youth does not emerge (perhaps due to the perceived futility of mobilization), it is possible that both the Principlists and clerical establishment would seek to mobilize their own mass protests to bolster their respective claims to political legitimacy. At this stage, the outcome of the election would largely depend on which side can more effectively interfere with the opposing sides’ mobilization. The relative success of this interference would be the ultimate measure of which side better controls the key institutions of the Iranian state, wielding the security apparatus to achieve a monopoly on violence.

In simple terms, if the Principlists can rally the Basij militia to break up protests, leverage VEVAK to halt threatening communications, and convince the IRGC to funnel resources into the whole operation, they can force the outcome of the election in their favor. This will be especially true if their ideological posturing resonates with voters. In this scenario, the Supreme Leader and his allies may find themselves marginalized to an unprecedented extent, perhaps lending some credibility to the claim that the Islamic Revolution is over. But contesting power in this manner is, for the Principlists, the ultimate gamble. Should the influence of the Principlists over the security apparatus prove fickle, and should the supporters of the Supreme Leader successfully manipulate the outcome of the election as well as any subsequent unrest, the Principlist-Militarist complex will crumble under the weight of its own expectations.

The Principlists have maneuvered into a position of great political opportunity. What remains is a fundamental reimagining of Iran’s national security strategy in order to reprioritize the country’s economic and political wellbeing. With the potential rise of Esfandiar Rahim-Mashaei and the Principlist faction’s influence over the IRGC and VEVAK, the prospect for the return of pragmatism to Iranian policymaking is encouraging. Normatively speaking, this analysis lends itself to some unexpected conclusions. Iran’s democratic processes are not robust enough to mediate the power struggle between the Principlists and the clerical establishment (the electoral mandate has historically been little more than incidental to the maintenance of power for both sides). The question of who governs legitimately will be precisely determined by the exercise of political violence. In which case, it is desirable that the Principlists fully control the security apparatus, if only because this will ensure the quick resolution of any unrest. While this is not to say that the Principlists represent an ideal leadership for Iran’s long-suffering citizenry, should the infighting between the various factions within Iran continue to “unravel” the capacities at the core of the state, then not only will crucial decision-making processes continue to deteriorate, but so too will the ability of Iran to modulate its own behavior toward the international community and the general population. Lamentably, the conditions are such that shortchanging democratic institutions is a small price to pay for the cohesion of the Iranian state.

Only progress on the basis of strength can weather the severe geopolitical and socioeconomic pressures that Iran faces. The only reasonable policy reformulations are those that ensure an internally strong state able to coordinate and direct the instruments of foreign and domestic policy at the level of state bureaucracies, especially in the realm of security. For the Principlists, patience in the place of brashness and pragmatism in the place of dogma are the values necessary to ensure the survival of the faction and, in turn, the survival of the state.