The Christian Right Angle

Out of the exponential growth of the European extreme right has emerged a new archetype – the intractable and furious Islamophobe. The Islamophobe cares about one issue only: immigration. Afraid of economic competition and cultural dilution, the Islamophobe reacts with violence, hatred, and bigotry. In the press this individual becomes “anti-immigrant,” “anti-Muslim,” a “right-wing racist,” or merely someone who is “scared” and “hysterical.” The Islamophobe does not have any tangible beliefs or ideology of his own. He is a negative force who, if the specter of immigration were to disappear, would slowly fade away. To buy into this popular image, however, is to accept a starkly reductive vision – a one-dimensional characterization of the extreme right that ignores the movement’s own ideology and independent identity.

Out of the exponential growth of the European extreme right has emerged a new archetype – the intractable and furious Islamophobe. The Islamophobe cares about one issue only: immigration. Afraid of economic competition and cultural dilution, the Islamophobe reacts with violence, hatred, and bigotry. In the press this individual becomes “anti-immigrant,” “anti-Muslim,” a “right-wing racist,” or merely someone who is “scared” and “hysterical.” The Islamophobe does not have any tangible beliefs or ideology of his own. He is a negative force who, if the specter of immigration were to disappear, would slowly fade away. To buy into this popular image, however, is to accept a starkly reductive vision – a one-dimensional characterization of the extreme right that ignores the movement’s own ideology and independent identity.

This crude portrayal of the European right wing does hold some truth. The rhetoric of the extreme right wing – a collection of groups both separate from mainstream conservative parties and sharing affinities with “some combination of racism, xenophobia, nationalism, and a desire for a strong state and law and order” – is undeniably vicious and discriminatory, despite its careful attempts at circumlocution, according to scholars Kai Arzheimer and Elisabeth Carter.

Incidents of misdirected violence, such as assaults on Sikhs rather than Muslims, also speak to the racist tendencies of many identifying with this brand of conservative politics. These racist, cruel, and prejudiced attitudes clearly identify the extreme right wing as a dangerous and destabilizing force within a rapidly pluralizing Europe. Yet such a depiction also fails to provide adequate insight into a movement that continues to influence European public affairs. Instead, one should emulate 20th century intellectual Hannah Arendt’s determination to “take seriously” even the most horrific ideologies, to sketch the beliefs and intentions of groups whose actions seem to defy all rational interpretations.

To do this, we must engage with the right wing itself, especially its Christian views. The concept of “thin” religion, which privileges abstract religious identity over concrete practice, provides an especially useful lens through which to interpret the extreme right’s ideology. Seen from this angle, the extreme right coalesces around an ideal of Christian, Western civilization in the face of alien, corrosive influences. This specific genre of Christianity enables the extreme right to portray itself as opposed to immigration and as a coherent, ideologically independent movement.

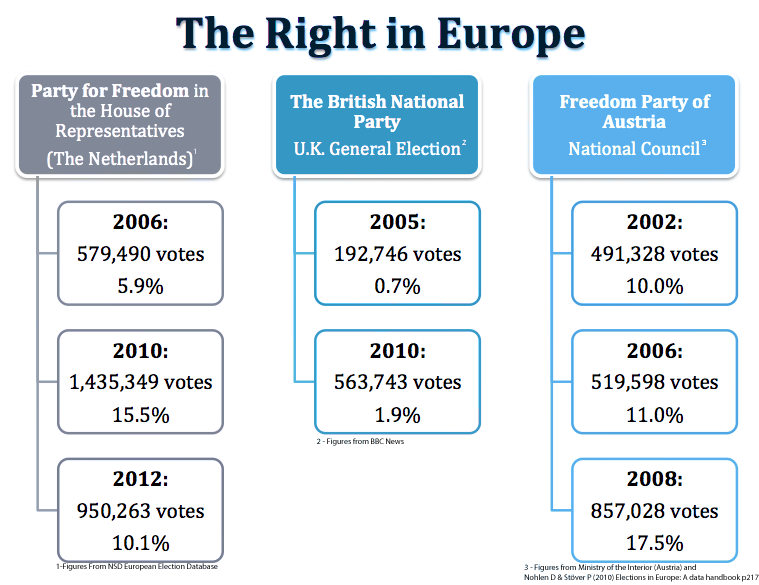

In various speeches and interviews given between 2009 and 2012, Geert Wilders, Nick Griffin, and Heinz-Christian Strache each spent considerable time discussing not only the perceived threat of Islam but the Europe they seek to protect. Wilders, president of the Dutch Party for Freedom, gave an address in April 2012 concerning the interaction of Islam and the West to the Gatestone Institute, a group which lists combatting “states which train children to be suicide bombers” as one of its primary aims. Heinz-Christian Strache, leader of the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) and a strident opponent of Turkish membership in the European Union, also spoke to a group affiliated with the right wing at a 2010 conference in Vienna. Nick Griffin, leader of the United Kingdom’s British National Party (BNP), alone chose to interact directly with a more politically moderate organization. His remarkably candid 2009 interview with The Independent illustrated the tension felt by right-wing parties entering into larger political arenas; Griffen has attempted to influence mainstream political discourse by adapting party policies and engaging moderate activists.

While all of these figures have attempted to position their policies and identities in concert with a certain interpretation of Christianity, it is also notable that all the three share very similar views regarding Islam. To Wilders, the debate does not concern religion. One must tolerate religion, but Islam does not fit that category. He says, “I have traveled widely in the Islamic world. I have read the Koran. I have studied the life of Muhammad. It made me realize that Islam is primarily a dangerous ideology rather than a religion.” In Wilders’ opinion, one need only glance at the Qur’an to ascertain the nature of Islam. As its nature is not that of a religion but a “totalitarian ideology,” the onlooker is justified in their absolute revulsion. Even the most liberal, tolerant Westerner feels disgust when confronted with Islamic ideology.

Griffin displays a similar hostility to Islam, which he also frames in terms of personal experience. “I’ve got no problem with Islam in the Middle East; I don’t think we should be there trying to make them westernized, that’s not our job, it’s not our right,” he explained in an interview with The Independent in 2009. “My problem with Islam is that I’ve read the Koran, time and time again, very, very carefully.” Griffin both mirrors and diverges from Wilders in that, instead of defining Islam like Wilders does – as a detrimental force wherever it exists – Griffin objects only to its presence in the United Kingdom. Elsewhere, he undercuts the very idea of a Muslim moderate, but most important to him is that Islam somehow conflicts with the essence of Europe.

Against this monolithic and threatening vision of Islam, Wilders, Griffin, and Strache build a sense of Christian identity with both powerful emotional resonance and sustainable outside direct connection to a Muslim “other.” Already from Wilders’ description of Islam, the listener knows that the West represents liberal ideals and tolerance. But how does Wilders positively define the West? He explains, “We have to believe in the superiority of our Western values. If we do not believe in our own Western values, we will not be prepared to defend them. That is why we have to end the biggest disease in the world today – the cultural relativism which pretends that all cultures are equal. This is simply not true. Our Judeo-Christian and humanist civilization is far superior to any other civilizations like the barbaric Islamic civilization.”

Wilders points to a conflict that expands beyond religious difference – to a debate over foreign “cultures” that conflict with the superior Judeo-Christian, “humanist,” civilization. A closer reading suggests that this inclusion of secular premises functions only to support the centrality of religious superiority. First, Wilders places “Judeo-Christian and humanist civilization” in conflict with “Islamic civilization.” Wilders does not view Islam as a religion. This comparison, however, seems to accept that the rightful counterpart of Judaism and Christianity is Islam. An opposition of humanism and Islam would essentially endorse the value inherent in a purely secular view of the world, a position Wilders would not likely take. The discussion then centers on contrasting religious traditions. Second, Wilders consistently describes the acceptance of Western values in terms of having to “believe.” One does not rationally arrive at Western civilized values, as the humanist might. One must “believe” to defend this inheritance. Values become analogous to religion, an equation that again underscores the necessity of a Judeo-Christian, humanist civilization.

Griffin echoes this sentiment, and sets against a religious, Islamic danger a spiritually informed British people. Griffin repeatedly references the language of economics, discrimination, and mainstream political discourse. His most cogent arguments, however, rely strongly on religious concepts. He predicts, “I would say in 30 years it’s inevitable that Europe will face a decision which is absolutely unavoidable; between whether Europe will continue on the lines it is, which is founded on Christianity, on the identities, including ethnic identities, and if you must the colour of European peoples and on the secular and democratic traditions that grew out of our Christianity and our way of doing things, a choice between that and becoming an Islamic caliphate. There’s no question about it, the government figures show it.”

For Griffin, Christianity forms the bedrock of European culture. His repeated mention of Christianity implies a value in religion not associated with “identities” or “colour.” The use of a religious counterbalance – “an Islamic caliphate” – adds to the identification of religion as the primary source of European and British values and culture. He later elaborates, “I believe that Christianity is the fundamental [basis] of our culture, our freedom and our way of doing things. I believe it needs to be preserved and I oppose the way in which the liberal elite takes every possible opportunity to do it down and shut it out.” Griffin places Christianity as an influence superior to rationality or liberal thinking, specifying it as the direct source of freedom and modern values. One cannot separate Europe and Britain from Christianity, nor can a member of any differing religion, including Islam, assimilate.

Strache weaves a similar association of Enlightenment and liberal values with Christian history. He sees Islam as “an attack on our building that consists of values which has [sic] different roots: Germanism, Hellenism, and various floors, reaching up to the Enlightenment and Christianity, but also the Judeo-Christian roots.” He positions Islam as a system of values that cannot be reconciled with Austria or with the “Christian Occident.” Strache’s self-perception binds him to a sense of Christian identity explicitly religious, though not concerned with the everyday practice of the common churchgoer. Displaying his flair for solidifying abstract concepts, Strache references the turmoil surrounding the creation of Kosovo. Confirming the Christian nature of Europe, Strache explains the conflict was “fought for the preservation of Christianity in Europe.” Strache draws the borders of enlightened Europe neatly around its Christian inhabitants and likewise views himself and his political goals as religiously inspired.

Notably, Strache avoids explicit discussion of Christian theology and keeps his religious language perpetually vague and removed from ritualistic, daily religiosity. This again appears in Griffin and Wilders. Though Griffin relates Islam with attitudes, behaviors, and practical interaction with society, his view on Christianity’s influence on the individual is less clear. Griffin insists, “if there were a bunch of Christians who wanted to do away with [the separation of church and state] I’d oppose them.” Christianity can remain a potent influence in European life without dominating private behavior, whereas Islam, according to Griffin’s description of a “proper” Muslim, cannot. Christian identity undergirds the British extreme right and combats a growing Islamic threat, but does not dictate the everyday behavior of the movement’s members. Wilders, too, pairs religious language with the modern liberal discourse. He uses religious phrasing, yet refrains from discussing the theological content of Christianity, preferring instead to reference the broader categories of “civilization” and “heritage.” He ends by vowing resistance “even when we are marked for death” – a call that conjures visions of Christ’s martyrdom – but engages Christian imagery as a rhetorical device rather than as a source of theological reasoning.

Wilders, Griffin, and Strache each conceive of Islam as a uniform religious movement incompatible with European values. They derive these values directly from Europe’s Christian past. Though each certainly views the conflict through additional lenses of race, one cannot avoid the marked influence of religious language in their political rhetoric. This religious sentiment permeates the European extreme right wing, far beyond these three individuals.

The interaction of the extreme right with Christian conceptions of identity may reflect the ingrained tendency of Europeans to interpret Islam as symbolizing, in the words of Edward Said, “terror, devastation, the demonic, hordes of hated barbarians.” But a more subtle take on the religious language of the right, however, is to see this surge in religious identity as a reflection of the changing nature of religion itself. Columbia University Professor Sudipta Kaviraj offers a useful schema regarding this shift. Whereas traditional spirituality forms a thick religion, characterized by local and ritualized practices, modern religion similar to the European extreme right is a thin religion. Wilders, Griffin, and Strache each invoke abstract ideas of Christian society, thereby defining religion not as a collection of specific practices, per se, but as a loosely bound community united only by a shared set of principles and ideals. They then politically mobilize this community against a constructed Islamic threat. A thin version of Christianity permeates the language of the European right wing, including in the United Kingdom.

Christian identity – religiosity in its thin form – forms a crucial aspect of the European right wing that will not disappear with the resolution of immigration difficulties and instead continue to motivate the movement and inform its political orientations. But this thin Christianity also does not translate directly into policy. The ongoing tension within the European Union serves as a perfect example of the often-neglected interplay of religious rationale with more mainstream “secular” concerns. Groups belonging to the extreme right wing are almost without exception firmly opposed to a strong European Union. Their insistence on an international, Christian civilization, however, indicates support for an idea of a transcendent European unit. Obviously, the ability to argue for Christian unity from within the discourse of the extreme right does not necessitate the existence of such support, but it should at the very least destabilize popular conceptions of these parties as staunchly nationalist. If other interested parties seek to predict, counter, or compromise with the extreme right wing, a dismissal of the movement’s political ideology will only create a partitioned and ineffective political environment. Like immigration, the extreme right is not about to disappear. Understanding the movement’s intentions, political and religious, forms an essential step towards a more responsible interpretation of European politics.