News on News on News

In July 2010, the monsoon rains began in Pakistan. Most people within Pakistan took the rains as a matter of course, ducking inside and waiting it out. But this time the rains did not stop. The waters crept over the banks of the Indus River, submerging farms and homes, destroying the livelihood of thousands. 1.2 million homes have either been damaged or destroyed; today 4 million Pakistanis are homeless; and 8 million remain dependent on aid, but as the effects of the flood gradually unfold, those numbers will almost inevitably rise.

In July 2010, the monsoon rains began in Pakistan. Most people within Pakistan took the rains as a matter of course, ducking inside and waiting it out. But this time the rains did not stop. The waters crept over the banks of the Indus River, submerging farms and homes, destroying the livelihood of thousands. 1.2 million homes have either been damaged or destroyed; today 4 million Pakistanis are homeless; and 8 million remain dependent on aid, but as the effects of the flood gradually unfold, those numbers will almost inevitably rise.

In comparison, the earthquake in Haiti that occurred in January of the same year left 313,000 homes damaged or destroyed, 1.5 million Haitians homeless, and, almost a year later, hundreds of thousands of Haitians still dependent on aid. According to the Inter American Development Bank, the Haiti earthquake cost between $7.2 billion and $13.2 billion. The costs of the Pakistan floods just a month after they began were estimated to be $7.1 billion, according to a joint study by Bell State University and the University of Tennessee. However, even without having been updated since mid-August, the total estimates for the cost of the floods are as high as $15 billion.

Despite the comparable devastation in Pakistan, estimates of total damage did not immediately surface in the media. Whereas, in the case of Haiti, the numbers became readily accepted aid goals, the Pakistani floods did not receive such tangible benchmarks until later in the news cycle. Rather, the array of numbers presented-subdivided by types of aid and by duration, and different in almost every news source-were far from unanimous or clear goals.

The shifts and ranges in numbers do belie one fact-Pakistan faces a host of longterm repercussions from the flood, which will be hard to calculate and harder still to deal with on the country's minuscule budget. As detailed in the Atlantic Wire, challenges include:

loss of domestic infrastructure, faltering confidence in the government's competency, devastated agriculture causing future food shortage, exploitation of the situation by the Taliban, and vulnerability to future flooding.

But such wrap-up stories only came long after the initial flooding began. And while one cannot expect the full scope of any disaster to reveal itself immediately, the case of the Pakistan floods do raise questions of why such stories took particularly long to surface and why initial consensus on figures and fundraising goals were not reached earlier. Yet even those figures that were agreed upon early on and put forth by reliable actors resulted in a woeful showing-by mid-August, only one-fourth of the U.N.'s meager plea for $459 million in immediate aid had been met. Why was such a disaster, no more tragic but in many ways more severe and long-term than Haiti's earthquake, so hard to rally aid for?

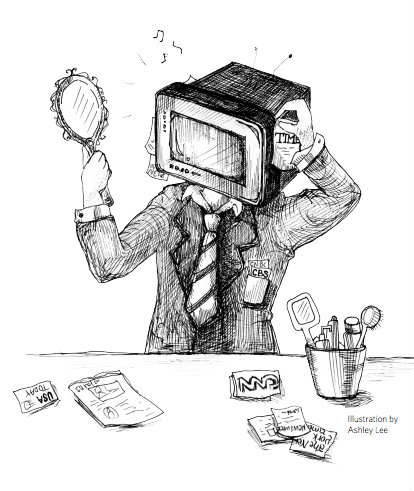

One can explain away this failure of humanitarian efforts in terms of donor fatigue, of caution towards the Pakistani government, of less visceral reactions to images of floods than images of other disasters, or other such excuses for Americans' hesitation hesitation in reaching for their pocketbooks. But ultimately the bulk of the blame must rest with the press-both in the initial coverage they gave to the crisis and in the timing and nature of their reflections upon the initial flooding.

In the wake of the Haitian crisis, American news was inundated with images of the aftermath. The New York Times alone reported over thirty stories on the earthquake within less than a week. In addition to these stories focusing on hard facts and vivid images, news organizations ran long and detailed lists of outlets for donations. One of many New York Times pieces devoted exclusively to helping Americans learn how to donate to Haiti listed over twenty verifiably sound and active aid organizations. In contrast, the New York Times ran less than a dozen articles on the Pakistani floods within the first week of the crisis. And within the week of the immediate outbreak archival searches revealed no lists of organizations to which Americans could donate like those released for the earthquake.

In February, a month after the Haitian earthquake, the headlines of USA Today still read "Jolie visits Haiti survivors in Dominican Republic," "U.N. Slams Haiti Hospitals for Charging," "Haitians Mourn Their Dead A Month After Quake," and "Haiti's Homeless Get Tarps, Want Tents." The content of the articles was concrete, quoting figures agreed upon in the past and building upon them with evolving and evocative pleas.

In mid-August, a month after a lull of coverage on Pakistan, a resurgence of articles on the floods came forward. But the nature of these articles differed greatly from those that appeared a month after the Haitian earthquake. An article in the Aug. 19 edition of the Christian Science Monitor claimed that "coming just 7 months after the Haiti earthquake, the Pakistani floods are coming at a time when the people who generally donate aid are feeling the pinch of a tougher economy.” Days later, on Aug. 27, Samuel Worthington, president of the humanitarian coalition InterAction, explained the dearth of giving to Pakistan to USA Today by Americans' view of the nation in terms of a small terrorist population. Even as recently as Nov. 10, the New York Times published a retrospective on the aid initially following the crises: "Five weeks after the Haiti earthquake, 48 aid groups polled by The Chronicle of Philanthropy had collected three-quarters of a billion dollars. Five weeks after the flooding in Pakistan, a similar poll found 32 aid groups had collected just $25 million." This lament was followed by a compilation of reasons for poor donation showings: mistrust of the Taliban, donor fatigue, and even self-implication of the press for not providing enough immediate media attention. But, notably, none of these articles engaged seriously in further reporting. None made an attempt to provide firm numbers or new data to match the style of reporting seen a month after the Haitian earthquake. And, most strikingly, even after some sources implicated their own inactivity in initial reporting as a detriment to aid efforts, they made no serious effort to remedy the situation by providing information that would compel donations.

The voice of coverage a month after the Pakistani floods shifted dramatically from underreporting to pure analysis. The tendency became not to give updates, new views on the crisis, or new appeals or avenues for donations, but to provide stories justifying the poor showing of aid and the lack of initial coverage. American readers, having few other avenues to learn about the disaster in Pakistan than through the news, were provided with ready-made excuses for their own inactivity as donors. And rather than a call for more donations, the shift to an analytical, post-game voice in the news created for many the impression that the crisis in Pakistan, rather than unfolding as it was, had reached its conclusion-a point at which donations need no longer be entered. The story in the press had largely been written albeit implicitly: Showings in aid for Pakistan had been poor, and there were reasons for the deficiency. It was tragic, but it was also one of the few facts upon which all the news sources could soundly and consistently agree.

This should not imply that the gap in coverage and content between Haiti and Pakistan was a result of some press plot or pure laziness. The floods were not an easy story for the press to cover. Floods are gradual disasters by nature, and the effects come in subtle waves that, though building and compounding the crisis, can often seem like more of the same story. The press, seeking readership and ads, thrives on breaking news and shocking, jarring events. Since the press could not predict the weather, that is to foresee where the worst images and stories would come from, and found it difficult to paint terrible but similar tragedies in ways that made them seem fresh to readers, it is no wonder that they dropped the ball on the story.

The stories that do develop distinctly are more mundane than images of mangled bodies on the rubble. Crops were drowned and lands ruined and, as Pakistani farmer Maqbool Anjum told the New York Times, "it'll take three or four years until [they] can grow anything on [their] land again." But try to capture that concept-the gradual overwhelming of the land and resources-in a photo or a compelling article. As Kenneth Ballen, founder of Terror Free Tomorrow, told the Christian Science Monitor, "it is a less visual, less dramatic and immediate disaster, even if it threatens to be a far greater one [than Haiti]."

It is true that, in the end, "the images coming out of Haiti were highly compelling […] Children screaming for their mammas, people with awful wounds, these buildings just pancaked. With Pakistan you saw a few people wading through ankle-deep, maybe knee-deep water," as Randy Strash, strategy director for disaster response at World Vision, wrote in the New York Times. But this does not mean that there were not similar pictures to take in Pakistan. The rush of rains in their initial onslaught and the washing away of homes make for compelling footage. But the floods came suddenly, often too suddenly for reporters to appear, and the initial floods had almost completely blocked press access to most of the worst-hit locations.

Publishing stories as often for Pakistan as for Haiti, although the two involved comparable chaos and destruction, would have seemed a dogged and repetitive story for the reporter blocked from access and missing opportunities, for the editor, and for the reader.

The same features of changing and unpredictable conditions and limited access meant that, whenever they did report on the floods, their facts and figures were so wide-spread as to be questionable to readers. Even as late as Aug. 1, the New York Times reported that "estimates of the death toll […] ranged up to 1,100, although the national government put the figure at 730. The nation's largest and most respected private rescue service, the Edhi Foundation, predicted the death toll would reach 3,000." At such a late date, not to have reached closer consensus on figures robs the public of a clear sense of severity, of importance, or of a goal to reach for in donations.

But with little demand or capacity for daily thorough and definitive reporting on the unfolding disaster, the press lacked the volume of data to come to general consensus on the median figures. And as these figures slid about, it became difficult to tell whether the situation in Pakistan had grown worse or better over the course of the floods, as the higher estimate used for one week would be greater than the lower estimate used for the subsequent week, when the absolute magnitude of the disaster had definitively increased. The situation grew murkier and murkier until the coverage had passed and, when some numbers were agreed upon, the time had already come in the press to assess the failure of donations as opposed to the time for further reporting.

But the fact that reporting was difficult and the story hard to sell did not necessitate the response of the press. In fact, arguably, the turn towards analysis a month after the floods undermined the integrity of the press and raised serious questions as to the press's recognition of its own role in disasters.

Drumming up aid for individuals in need after a humanitarian crisis is the norm for the press. The New York Times explicitly recognized this duty when, in November, it published an article stating that "attention from the news media, particularly television, is another crucial driver of donations [… and] Pakistan did not get nearly the kind of coverage that Haiti did." Their response to Haiti- the publishing of lists of viable charities-also underscores a recognized commitment for helping to raise and channel relief funds. And, needless to say, the American response in Haiti, as well as in the 2006 tsunami and a host of other disasters, demonstrates an expectation from the world, as well as from ourselves, that Americans should set a strong example in the initial response to humanitarian disasters. But even after recognizing their failure to fulfill this task in the wake of the floods, the media failed to correct its mistake and double-time to provide outlets and reasons for relief funds to come in.

Latching onto a sexy political story in the wake of the floods, like explaining away a lack of donations in terms of U.S.-Pakistan relations, is undoubtedly interesting. It is true that the disparity between the U.S. government's pledge of $1.15 billion in aid over two years for Haiti in addition to the $100 million pledged days after the quake by President Obama, and the mere $200 million promised by the U.S. to Pakistani relief may speak to tensions between the two governments. And it is true that these figures make for an interesting vehicle by which to explore accusations against the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence agency involving its complicity with the Pakistani Taliban, resurging violence, and anti-American sentiments and actions. The murky nature of the U.S.-Pakistan alliance needs serious scrutiny. But when the press recognizes its role in the aid process, it should recognize the inappropriate nature of latching onto a story that redirects focus for Americans thinking about Pakistan and casts doubt over whether or not Americans should support a humanitarian disaster.

The role of the press is to provide hard facts, and in the case of a humanitarian disaster these hard facts are all the more vital for rallying support and response. The press is aware of these duties and of its impact upon donors. If, as happened in the case of Pakistan, the press acknowledges its obvious and marked initial failure to provide enough concrete and compelling reporting on a major crisis, then the press should, in keeping with its mission, fill the gaps and correct its error post-haste. In the case of Pakistan, though, after the press recognized its own failure, it proceeded to scrutinize its own faults in covering the event and to explain away the lack of giving. The press lost sight of its purpose and of its lofty, ideal goals-it skipped hard reporting and calls for aid and moved directly into speculation and apology. The lack of continued reporting led to an incomplete picture of the floods, and even that picture was fragmented. Certainly the conditions the press used to explain low aid are valid-the timing was bad, the situation was hard. But they do not explain the full extend of the miserable showing and they do not excuse the way the press handled the event. Worse yet, these explanations may even have led to the misguided impression that the floods were too far in the past to warrant urgency and aid.

Perhaps there is a certain irony in using a press article to identify the press's complicity in the initial failure of aid efforts in Pakistan, especially when the analysis it provides of that failure cites a focus on analysis over reporting as a primary cause of the failure. But this is a reminder of what has happened: On Aug. 16, among the resurgence of analysis and articles bemoaning and explaining away minuscule donations to aid efforts, U.N. spokesman Maurizio Giuliano reminded the world that "there was a first wave of deaths caused by the floods themselves […] But if we don't act soon enough, there will be a second wave of deaths." Giuliano's predictions of death and destruction came true. And failing to fulfill the duties of the press-even the unofficial duties to present and muster support for unfolding crises-in favor of exploring and analyzing failures will lead to future deaths as Pakistan continues to go without adequate aid. The impact of the Pakistani floods will unfold over years, and though it may feel tired or stale, unsexy or inaccessible, continued coverage treating Pakistan as a source in need, not a finished issue to be picked apart, will be vital in preventing these continuing effects of decaying infrastructure, destroyed crops, and homeless populations from taking perpetual but invisible tolls upon an already haggard population for years to come.

The story continues to unfold. Pakistan continues to suffer. It is not too late to redirect our coverage to the hard facts-to making the disaster as fresh and important in the news as it is in reality on the ground. Nor is it too late to begin donating or simply raising awareness about the conditions in Pakistan. Rather, it is time for the news to end the practice of looking inward, of covering its own lack of coverage or explaining why interest has faded. Though this call may seem unrealistic, it is time for the news to return to hard reporting where it is needed, not just when it is convenient or sexy. It is time for us to start caring again about Pakistan-and for some to start caring for the first time.

For a list of charities active on the ground in Pakistan verified by the U.S. government and their contact information, as well as upto date cables and links to stories from the frontline of the relief effort, visit the U.S. State Department's "Pakistan Flood Disaster Relief" page: http://www.state.gov/p/sca/ci/pk/flood/ index.htm.