Bubba’s Playbook

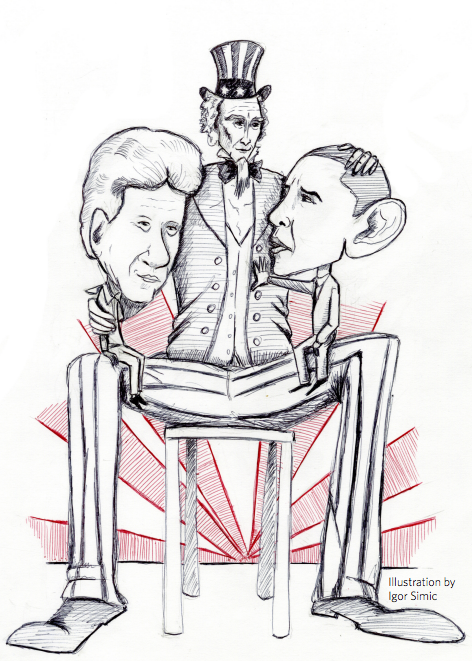

Just under two years ago, a young Democratic president took office after leading his party to majorities in both chambers of Congress, reshaping the political landscape after a period of conservative dominance. After enduring bruising legislative battles on top priorities like comprehensive health care reform, the Democrats stand to lose both the House and the Senate, and a new generation of Republicans is waiting to deliver on a much-hyped manifesto for change. To top it off, the president’s prospects for reelection aren’t looking particularly promising either. That this could be said of two Presidents—Bill Clinton in 1994 and Barack Obama in 2010—says two things. Mark Twain was probably right when he said that history doesn’t repeat itself; it rhymes. But given the points of similarity that do exist, Obama should expect the worst and make use of the lessons of 1994 to understand how he can thrive with a Republican-controlled Congress.

Clinton not only went on to be reelected, but even more remarkably, managed to spend most of the time after the Democrats’ 1994 midterm defeat outmaneuvering and outsmarting his Republican foes. How did he do it? More importantly, what lessons does the story of Clinton’s comeback hold for Obama?

Just under two years ago, a young Democratic president took office after leading his party to majorities in both chambers of Congress, reshaping the political landscape after a period of conservative dominance. After enduring bruising legislative battles on top priorities like comprehensive health care reform, the Democrats stand to lose both the House and the Senate, and a new generation of Republicans is waiting to deliver on a much-hyped manifesto for change. To top it off, the president’s prospects for reelection aren’t looking particularly promising either. That this could be said of two Presidents—Bill Clinton in 1994 and Barack Obama in 2010—says two things. Mark Twain was probably right when he said that history doesn’t repeat itself; it rhymes. But given the points of similarity that do exist, Obama should expect the worst and make use of the lessons of 1994 to understand how he can thrive with a Republican-controlled Congress.

Clinton not only went on to be reelected, but even more remarkably, managed to spend most of the time after the Democrats’ 1994 midterm defeat outmaneuvering and outsmarting his Republican foes. How did he do it? More importantly, what lessons does the story of Clinton’s comeback hold for Obama?

Sex scandals and impeachment trials notwithstanding, Clinton enjoyed enormous successes as President. The economy boomed. He presided over a federal government with a projected budget surplus for the first time since 1969. He signed a landmark welfare reform bill. Newt Gingrich was embarrassingly deposed as Speaker of the House just four years after taking office, reflecting the reversal of his party’s fortunes. President Clinton left the White House with high approval ratings and great goodwill. He has long been marked as one of the most gifted politicians in modern history, but his turning the tide so decidedly in his favor easily ranks as one of the most surprising and important comeback stories in American politics. Surprising because after losing Congress in 1994, Clinton was practically a lame duck. Important because as even casual political observers will note, Obama may very well find himself in Clinton’s shoes in just a few short weeks.

It is very rare for presidents of either party to pick up seats during midterm elections. What distinguished 1994 from many other midterm election years was the extent of the political damage done to the incumbent President. In 1994, voters rebuked President Clinton for overreaching on a mandate that was, in fact, much wobblier than Obama’s. By trying to advance a liberal agenda on issues ranging from the economy to gays in the military to his disastrous attempt at comprehensive health care reform, Clinton received backlash from a skeptical and uneasy electorate. The country had not turned its back on Reagan’s still-potent legacy; rather, voters put a moderate Southerner into office with under 40 percent of the national popular vote. Clinton made the mistake of attempting to make sweeping changes that were largely out of step with what the country wanted. This, paired with a sluggish economy and Americans’ time-honored convention of midterm reversals, resulted in a blowout that swung 54 seats in the House and 8 seats in the Senate to the Republicans.

Having lost both chambers of Congress and virtually all of his political momentum in this “Republican Revolution,” the President was faced with a choice between lame-duckhood and handing Newt Gingrich and the Republicans “carte blanche.” Obviously, neither was acceptable, so Clinton went back to his Southern Democratic roots—he triangulated. Rather than taking a left turn to rally the Democratic base (historically a bad move, since the true balance of power in American politics lies with independent voters and moderates), Clinton co-opted Republican prescriptions like welfare reform and a pro-growth stance on economic issues while at the same time using the art of compromise to institute incremental, moderately progressive programs like the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. The net effect of Clinton’s Third Way politics was to move the country forward in ways that attracted bipartisan support, both in Congress and the electorate.

President Obama will have to learn very well from 1994, as it now appears that he will lose the House and retain the senate by a razor-thin margin. The key to Clinton’s recovery was his understanding, at the most basic level, of the political dynamics of the country, and his ability to put those insights to effective use. It has been argued that Clinton possesses truly unique assets that Obama does not, such as his noted ability to empathize with the American people and the slipperiness that so many still associate with his political persona. These traits line up exactly with two of Obama’s perceived weaknesses as a politician: his often aloof persona, professorial style, and ironic inability to talk his administration out of trouble. But such critiques of Obama’s political ability are misplaced. It is important to note that Obama came to national prominence on the basis of a powerful personal narrative and soaring rhetoric, and that throughout his political career, from the Jeremiah Wright controversy to his alleged status as a closet Muslim to the health care debate, Barack Obama has shown prodigious ability to rise to the oratorical occasion.

Speeches alone will not be enough, of course. The Republicans will benefit from the continuing fallout from the sluggish economy and the government’s bailouts of big business.

And increasingly the GOP has countered its label as the “Party of No” by moving a set of young, articulate intellectuals like Eric Cantor of Virginia and Paul Ryan of Wisconsin to center stage. The latter’s budget plan, while debated in policy circles, has drawn praise for being clear-sighted and reality-based in its approach to America’s fiscal problems. The fact remains, however, that while the Obama administration is bruised, the president’s opponents doubt his ability to recover at their own peril. Barack Obama has the weapons to get back up and start fighting; he just needs to know how to use them. For that he needs to pick up a copy of Bubba’s playbook.

“I disagree with you, but I don’t think you’re Hitler.” That comedian Jon Stewart is holding a Rally to Restore Sanity at the end of this month based on this sentiment speaks volumes about the popular appeal of centrism and civil, moderate discourse. One of the basic facts of American political life is that elections are won in the center. Both Clinton and Obama took note of this early on in their presidential campaigns for the presidency and used it to their advantage. Interestingly, however, both lost the center ground (and thus political momentum) during their first two years as president, contributing to their losses in the midterms.

In general terms, both Presidents tried to effect sweeping “generational” liberal reforms on questionably robust mandates, such as comprehensive health care reform. And they did so in ways which ultimately hurt their standing with a majority of voters. The minutiae of these political battles are not of direct concern to the midterm elections; there are too many factors involved to make sweeping statements about the effect of a few particular bills. What is clear is that after losing in 1994, a politically chastened Clinton moved back to the center (to his roots as a founding member of the Democratic Leadership Council) as a matter of necessity—it was the only way to remain relevant with the GOP in control of Congress. The Clinton who declared that the “era of big government is over” and pronounced an “end to welfare as we know it” was not the President Clinton who tried to pass HillaryCare or allow gays to serve openly in the military. Signing the Defense of Marriage Act and advocating for free trade (one of Clinton’s few early successes) might have been anathema to some on the left, but they were supported by a country that was, and remains, largely center-right.

Landmark pieces of legislation like the Recovery Act and health care reform may have reached Barack Obama’s desk, but they have become a rallying cry for those who see a federal government growing too big, too fast. The raw political power of fiscal conservatism in the current environment cannot be underestimated. A less ambitious federal government, and by necessity, a less expansive progressive agenda, will be the price of Obama will have to pay in his second term. Just as Bill Clinton did the unthinkable and compromised with Republicans on welfare reform, Barack Obama will likely have to settle for cuts in discretionary spending and retain the Bush tax cuts for all income brackets, at least until the economy has recovered. The key for the President is to counterpunch the Republicans effectively. If he can co-opt parts of their agenda in the same vein as Clinton’s welfare reform gambit (tax and budget reforms come to mind here), he can score points with the electorate, throw the GOP off balance, and improve his political position, ultimately resulting in better, more measured policy solutions to the problems facing America.

The Congressional Republicans during Barack Obama’s first two years in office have been nothing but consistent. They have attempted to obstruct every major initiatives (and most minor ones) of this administration and the result has been gridlock. It could be argued that the kind of centrism espoused by Clinton would simply be met with continued opposition as the Republicans try to position themselves to retake the White House in 2012. But key domestic problems like the economy, tax policy, energy and immigration, all demand realistic, substantive policy prescriptions crafted by both parties. Such compromises may seem unattainable given the bitter partisanship that currently grips the political arena, and indeed, they probably are. The essential factor that will break the gridlock is a president who will find a way to force the Republicans to become a part of his government. Moderating his approach is only the setup for this more important, but riskier, step.

It took a shutdown of the federal government for Clinton to gain the upper hand over Republicans in 1995. An impasse in negotiations over the 1996 budget forced the shutter of nonessential services for several weeks in late 1995 and early 1996. While Republicans blamed Clinton for the debacle, he argued that their proposed cuts would harm the country, and more importantly, allowed Newt Gingrich’s behavior during the episode to severely harm his standing with voters. By deftly handling the Republicans and allowing them to make unforced errors, Clinton ultimately backed the GOP into a corner. The 1995 shutdown was the high-water mark of the Republican Revolution, and while the partisan bickering continued, the Republicans had pushed the outer limits of the public’s tolerance for such antics. After that point, with the Republicans as partners in delivering major pieces of legislation, such as the welfare reform bill in 1996 and the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Clinton made real progress.

Barack Obama should expect obstructionism from Congressional Republicans in the wake of their midterm gains, but he need not be resigned to it indefinitely. With unemployment at 9.6 percent, the Republicans will have no choice but to work with the President, and vice versa. Whether they do so willingly or due to their own mistakes is ultimately irrelevant, but Clinton’s example is instructive: It would be best for Obama to wait until an opportune moment and call the Republicans’ bluff rather than try to appear conciliatory right away.

Appeasement would weaken his negotiating position, and worse, could make him look ineffective if he is rebuffed. The best place to corner the Republicans, just as during the Clinton years, will be on the inevitable confrontation over the budget. Predictably, Obama will be opposed to the fiscal plans of the Republicans, which will likely include austerity measures of some kind. The prospect of cuts in popular programs naturally works to Obama’s favor, but the key will be for Obama to strike the right balance between political expediency and prudent policy, as Clinton did to great effect.

The way back for Obama is fraught with difficulty, given the depth of the anger in the country and the damage done to his political “hope” branding. There is also some suggestion that the departure of Clinton-era players like economic adviser Larry Summers and outgoing Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel will increase the influence of less pragmatic voices within the administration and drive Obama further left. That would be a fatal error. Such a shift cannot be ruled out, but the factors involved weigh heavily against it. President Obama’s tight-knit inner circle of advisers is filled with brilliant strategists, and this must be extended to include interim Chief of Staff Pete Rouse, who brings a wealth of experience, contacts, and perspective to the job.

As students of political history, Obama’s advisors are well aware that ceding the mantle of centrist, common sense governance to the Republicans would put a gun to the head of the Democrats’ future electoral prospects. And fighting for election in 2012 on the basis of President Obama’s uneven and unpopular record would pull the trigger. The two rules which guided President Clinton paved the way for his eventual comeback—take and keep the center ground, and force the Republicans to take ownership—are directly applicable here. If the President takes note of these lessons of recent political history, then his—and the country’s—chances for success will improve greatly, perhaps beyond what would have been possible if his party wins the midterms. If he does not, then chances are we’ll have to say goodbye to Obama in 2012 and throw Barry’s playbook onto the trash heap of history.