The Wright Stuff

Frank Lloyd Wright had a useful hint for the contemporary urban planner: “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.” As sentimental as this advice might sound, the role of nature in the context of the built environment is no light concern in the minds of policymakers and planners today. In a nod to the spirit of these “green” times, two current New York exhibitions are exploring the realities and potentials of this role—and in so doing offer two contrasting ways of approaching an understanding of the relationship between the built form and its underlying ecosystem.

In a show whose scope stretches across a century of architectural history, the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibit In Situ: Architecture and Landscape explores the sprawling variety of attitudes towards nature expressed in modern building design. The models and designs on display—among which are two of Wright’s own plans—serve as a catalog of 20th century architectural fancy, from its most starkly functional to its most beautifully flamboyant.

Frank Lloyd Wright had a useful hint for the contemporary urban planner: “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.” As sentimental as this advice might sound, the role of nature in the context of the built environment is no light concern in the minds of policymakers and planners today. In a nod to the spirit of these “green” times, two current New York exhibitions are exploring the realities and potentials of this role—and in so doing offer two contrasting ways of approaching an understanding of the relationship between the built form and its underlying ecosystem.

In a show whose scope stretches across a century of architectural history, the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibit In Situ: Architecture and Landscape explores the sprawling variety of attitudes towards nature expressed in modern building design. The models and designs on display—among which are two of Wright’s own plans—serve as a catalog of 20th century architectural fancy, from its most starkly functional to its most beautifully flamboyant.

For all their variety, the projects and designs gathered in In Situ tend to express a monolithic, top-down approach towards nature and the landscape, an approach based around an unchanging physical plan which, while it may express a degree of attention to the site’s natural context, fails to acknowledge complexity and flux. When it comes to building construction, the static plan has primacy over the dynamic, living site.

This is problematic even in purportedly ecologically-conscious design. Incorporating cookie-cutter “green” improvements into plans without concomitant attention to the specific natural habitats and relationships in any specific site poses the threat of ecological interruption, a threat left unexplored by MoMA’s exhibit. Closer to campus, a collaboration among Columbia and Barnard Architecture students, members of the Urban Landscape Lab at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, and the graphic design studio MTWTF has produced an imaginative new project called Safari 7. Through a variety of media, Safari 7 provides an interactive approach to understanding the dynamic set of habitats and ecosystems that weave through New York City’s unique built environment. This imaginative undertaking comes closer than almost any In Situ installment to answering Frank Lloyd Wright’s call.

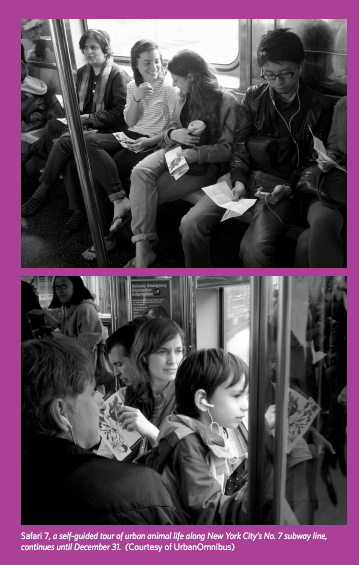

The project consists of a self-guided tour, aided by maps, signs, schedules, podcasts, and social networking tools, of the complex set of ecosystems that thrive in the urban landscape along New York City’s no. 7 subway line. While the exhibit at MoMA offers visitors a glance at the ways in which the architectural profession has historically interpreted, embraced, or rejected an often generalized view of the natural in building plans and designs—often to the detriment of the existing environment—Safari 7 facilitates an expansion of urban planning discourse, allowing city residents outside of the planning field to understand the complexity, diversity, and potential present in their own urban ecosystem. Such an expanded discourse—inclusive of the informed voices of those whose lives are embedded in a particular site’s set of ecologies, even ecologies as often overlooked as those of New York—might enable more flexible and site-responsive plans.

“We were interested in doing a guerrilla project,” explained Kate Orff, co-director of the Urban Landscape Lab, in reference to the project’s aim of engaging ordinary New Yorkers. “Reframing the Number 7 line as an urban safari forces you to experience the urban environment differently. ... This way, you’re not just on the receiving end of concepts brought to you by experts.”

Participants in this “guerrilla project” encounter the animal and plant populations that have adapted or become transformed through human intervention, from the estrogen-pumped fish ecologies of the East River to the swarms of Canada geese who seasonally congregate around the polluted man-made lakes in Flushing Meadows Park. The consequences of urban planning are made unusually palpable. “Safari 7 presents nature not as something pure and untouched,” explained Safari 7 Research and Design Associate Lisa Ekle, “but rather something that is constructed and constantly changing.” The project provides a channel through which members of the public can explore and engage with the specific set of diverse ecological relationships embedded in their own urban landscape. In doing this, it encourages a nuanced understanding of this relationship that holds the potential to challenge the at times unwittingly destructive approach taken by the projects and designs at In Situ.

The destructive implications of twentieth-century architecture and planning’s historical top-down approach are at their most jarring in a display at In Situ entitled “The Continuous Monument,” a shining, globe-spanning prism conceived in 1969 by the radical Italian architecture firm Superstudio. “The glass and steel monster would have extended ad infinitum across the earth, totally overriding the landscape, paying no attention to nature or even the existing man-made structures that might have stood in the way of its path,” explained Jennifer Gray, a specialist in architectural history who lectures at MoMA. As speculative as it was, the massive, and grimly monotonous, project can today be seen as nothing short of terrifying.

But the shortcomings of this articulation of man’s exertion of his architectural will over nature, evident even in purportedly ecologically-minded projects, signifies the need for an expansion in sustainable planning discourse of the type that Safari 7 makes possible. Take as example one drawing on display, entitled SITE, which envisions a big-box store rendered environmentally sound by the grass and shrubbery planted across its massive roof. “But the drawings are misleading,” Gray noted. “When you see the complete model, you see how massive the heat-trapping parking lot is.” Even in supposedly sustainable projects, the architectural field tends to marginalize ecological concerns for the sake of marketability to investors.

With its broad range of media tools available to anyone, Safari 7, by contrast, enables a grassroots, bottom-up engagement with the complex set of natural and man-made forces that operate across the urban landscape. “Growing awareness of habitats [fits with] a growing understanding of the less superficially technical and more emotional and compassionate side of the sustainability question,” explained Kate Orff to the Architect’s Newspaper. As architects and planners have “modified the globe to create human habitat all over the world. … People are beginning to expand their view and see that in some cases human habitat excludes animal life.”

“Most city infrastructure is constructed in a brutal way because government didn’t really understand how interconnected environment, health, and commerce were and are,” said Safari 7 collaborator Glenn Cummings, founder of the design studio MTWTF, in the same Architect’s Newspaper story. “It is the overlaps and intersections between these infrastructures, housing fabrics, human, animal, and plant habitats that tell the story.”

A note of concurrence with Safari 7’s egalitarian and interactive approach is struck by In Situ’s multimedia display “Non Stop Sprawl: McMansion Retrofitted,” by the San Diego-based urban research and design firm Estudio Teddy Cruz. A film clip to one side of a scale-model McMansion first queries: “Because of high gas prices the ‘supersize-me’ urbanism of the exurbs is coming into question. Will the tactics of adaptation determine the future of this oil-hungry urbanism?” The clip, filmed in front of a number of pristine San Diego homes, proceeds with a series of statements—all in Spanish—by the maids and gardeners who tend to the homes, regarding how the properties and the surrounding neighborhood might be improved. “These houses should have mixed uses. I think that would make for a more sustainable future,” says one interviewee. Other respondents suggest tearing down the fences separating the yards to allow for playgrounds and other collective activities, while others advocate infilling the space between the houses with commercial functions. The additional display screen, which at the beginning of the clip shows a diagram of a typical McMansion, responds to the ideas proposed by the interviewees, morphing and changing in accordance with their suggestions.

Incorporating the ideas of Safari 7, though, is fraught with economic and political complications. However, Estudio Teddy Cruz’s flexible and responsive approach to crafting socially and ecologically-responsible plans, as manifested on his exhibit’s second display screen, offers a possible vehicle through which the public understanding fostered by Safari 7 might be channeled into modern urban design.

“In terms of design and planning, I think the project supports the idea of specific and local interventions and how those then connect back to the greater urban environment,” said Lisa Ekle. “Ideally, city and park planning organizations would implement more policies supporting informal or less controlled borders between what we perceive as nature and the built environment.” But if the designs at In Situ offer any lesson, it is that informality and flexibility, when it comes to the relationship between construction and nature, offer challenges that, for developers, offset their benefits.

A broadened public understanding of the complex reality of the natural environment’s relationship with man-made construction, along with a concomitant responsiveness on the part of the fields of architecture and planning, is necessary for any positive change. The Safari 7 team hopes to take the project to schools, museums and libraries in Queens to further raise awareness of the habitats that exist within and throughout the urban environment. Only through a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of this relationship by all members of the community can sustainability become a recognized, clearly defined, and practical target at the urban scale.