Fake ID

During a speech in Milwaukee in mid-April, Barack Obama brought his talk back to a common campaign theme: “Our incapacity to recognize ourselves in each other.” That was an especially poignant point to make in front of the mostly black audience. Obama’s authenticity as a black man has been questioned publicly by a number of people.

The New York Daily News’ Stanley Crouch was vocal about doubting Obama’s black identity. “Obama did not—does not—share a heritage with the majority of black Americans, who are descendants of plantation slaves,” he said. And Debra Dickerson, writing for Salon.com, echoed Crouch, “Not descended from West African slaves brought to America, [Obama] steps into the benefits of black progress (like Harvard Law School) without having borne any of the burden.”

During a speech in Milwaukee in mid-April, Barack Obama brought his talk back to a common campaign theme: “Our incapacity to recognize ourselves in each other.” That was an especially poignant point to make in front of the mostly black audience. Obama’s authenticity as a black man has been questioned publicly by a number of people.

The New York Daily News’ Stanley Crouch was vocal about doubting Obama’s black identity. “Obama did not—does not—share a heritage with the majority of black Americans, who are descendants of plantation slaves,” he said. And Debra Dickerson, writing for Salon.com, echoed Crouch, “Not descended from West African slaves brought to America, [Obama] steps into the benefits of black progress (like Harvard Law School) without having borne any of the burden.”

In part because Obama’s dark skin comes from a Kenyan father and not from ancestors who were slaves in America, his black credentials have come under intense scrutiny. The scrutiny also stems, though, from a seemingly self-conscious effort by Obama not to run as the “black candidate,” as Jesse Jackson did in 1984 and 1988 and as Al Sharpton did in 2004. Sharpton too has questioned Obama’s commitment to traditionally black causes.

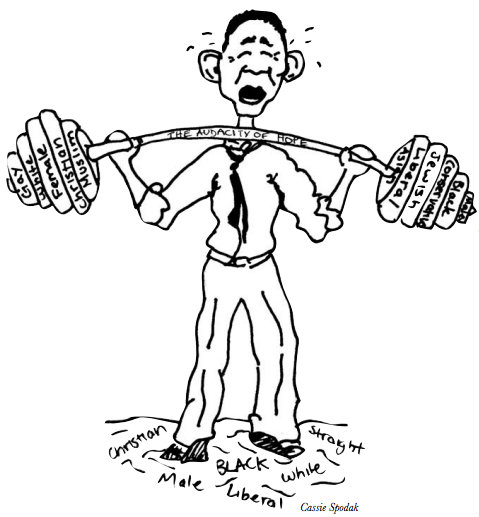

Granted, Obama eschews identifying exclusively as black, instead emphasizing his multi-racial and multi-cultural identity because by blood he is just as white as he is black. In doing this, Obama has become one of the most racial politics. Obama is exposing not only how simplistically Americans understand group identities, but also the extent to which the politics associated with those identities are overly touchy and intensely potent. Above all, he is asking Americans to look beyond the touchiness and the potency, to identify with him and thereby with each other.

Racial Geometry

American racial politics have long been dominated by a black-white divide stemming from America’s tortured (and tortuous) history of slavery and an ongoing hostility between the black and white communities. Fairly recently, though, notions of race in America have expanded beyond black and white to a new framework, what some call the “ethno-racial pentagon”: five categories that mark Americans as (1) white, (2) black, (3) Hispanic, (4) Asian, or (5) Native American.

While for many the choice is easy, the notion that everyone should fit neatly into only one category is illogical. It is especially so in the context of the five-sided framework’s origin: a somewhat obscure 1977 directive from the Office of Management and Budget intended to standardize Census statistics pertinent to enforcement of the Civil and Voting Rights Acts.

The categories were meant merely as statistical generalities, but they have become “so much the way [race] is constructed,” said Barnard Political Science Professor Raymond Smith. But in which category does someone belong when he or she can claim membership in all of them? This question led the office to revise the instructions in 1997. From then on, a respondent could check one or moreidentity boxes, making room for what Columbia Law Professor Patricia Williams calls, “A new-age Tiger Woods-ish formulation,” referring to the champion golfer—of black, white, Asian, and Native American heritage—who once classified himself as “Caublanasian.”

Obamerican?

Tiger Woods, though, was racialized—that is, racially identified, particularly by the media and public—as black. In part, such identification is based on appearance, which is a dominating factor in American racial identity. But it is also the legacy of the one-drop rule, which stipulates that if a person has one drop of black blood he or she is black. The rule was born of “white-supremacist, racist ideology, which in many ways permeates American history,” says Smith.

Tiger Woods and Barack Obama are black enough to be subjected to the one-drop rule, but other enough to be criticized by blacks for their lack of black-American heritage. But why does that matter? The success of the Civil Rights Movement, in some ways, provides an answer, because to be sure, says Williams, there are “people who grumble about the piggy-backers.” She is referring to black people such as Dickerson and Crouch who practice a sort of reverse one-drop rule, under which the gains of the Civil Rights Movement should go only to the descendants of black slaves. But regardless of such insistence, the Civil Rights Movement has proven much broader, argues Williams: “Of course it should be expansive enough to encompass Barack Obama’s complex, maybe unusual, but in another sense really quite iconic American identity.”

Throughout his recent political career, Obama has played up the complicated background that gave birth to that complex identity: Kenyan father, Kansan mother; raised partly in Indonesia by his mother and her Indonesian husband, partly in Hawaii by his mother’s white parents. Obama also claims to have Native American ancestry, and in March it was reported that some of his distant forebears owned slaves. Such a genealogical trail is not in itself surprising, “many people descended from slaves have slave-owning ancestors,” says Paula Moya, former director of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity at Stanford. But it was a genealogical excavation that has been highly talked-about in light of the many questions regarding the ‘authenticity’ of Obama’s blackness. For those asking the questions, having slave-owning ancestors serves to high- light the fact that Obama does not have any slave ancestors.

“Part of what [those who question Obama’s blackness] are saying is that there is something about being black—as opposed to being an American of African descent—that has to do with a legacy and an experience that come down through your family, and part of that experience has to do with being the descendants of slaves,” Moya explains. In responding to the revelation of Obama’s slave-owning ancestors, though, Obama’s campaign hit a persistent note, saying that the candidate’s ancestry is “representative of America.”

Though sidestepping the concern about Obama’s having slave-owning ancestors but no slave ancestors, that response cut to the core of Obama’s relation to identity politics. Obama’s campaign has been almost entirely based on his individual identity. Other than questions of his support and identity within the black community, the most persistent critique dogging Obama has been his lack of substance. Much of this critique comes from a combination of his lack of political experience and the high-minded rhetoric about American politics he favors, but much of it also comes from Obama’s almost stubborn insistence on talking about his personal history.

And yet people respond to, and are inspired by, that history. As Obama said in his keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention: “I stand here knowing that my story is part of the larger American story, that I owe a debt to all of those who came before me, and that in no other country on Earth is my story even possible.” In a way, Obama is subverting the critique: his identity is substantive; it is as much a part of his appeal as a candidate as any position he might have on an issue. The Transitive Property of Barack Obama

Whereas campaigning on personal identity is about single words or phrases for many candidates—Vietnam for McCain and Kerry, Clinton woman for Hillary—Obama’s identity requires hundreds of words and phrases and articles. He often attacks the “smallness of our politics;” the groups Americans have created for themselves and for others are too small for Obama.

In that same speech in 2004, Obama spoke of his vision of social justice: “If there’s a child on the south side of Chicago who can’t read, that matters to me, even if it’s not my child… If there’s an Arab-American family being rounded up without benefit of an attorney or due process, that threatens my civil liberties.” Through this kind of rhetoric, Obama is not only enlarging American conceptions of racial identity, he is also using his own identity as a nexus through which Americans can connect to those with whom they otherwise might not identify—Obama is asking Americans to identify with him, and through him, with each other.

“He personifies, more than any other candidate, a diverse constituency of the US, and in that sense people are more easily able to identify with him personally,” says Columbia political science professor Dorian Warren. “He can take them there, and he can say, ‘Okay, now that you’re seeing through my eyes, let’s look around at these problems and see how they affect us,’ even if [those people] don’t seem to be connected at first glance.”

Obama, in his rhetoric and person, points out the fiction in the perceived simplicity of American racial identities. But Americans, in questioning Obama’s group identification, insist on the potency of those identities. Still, before there were questions about Obama’s blackness, some called Obama a “post-racial” candidate, a candidate who signaled the end of racial and ethnic group identity politics in America. But, Moya argues, “If race didn’t really matter, we wouldn’t be talking about this.” And all that talking, she remarks, “says a whole lot more about us as a country than it does about Obama.”

Obama is hoping Americans are ready for a leader who represents an America that has moved beyond simple racial identities. Most telling will be what American voters have to say.