SWC’s Contract: A Win for Student Workers and the National Labor Movement

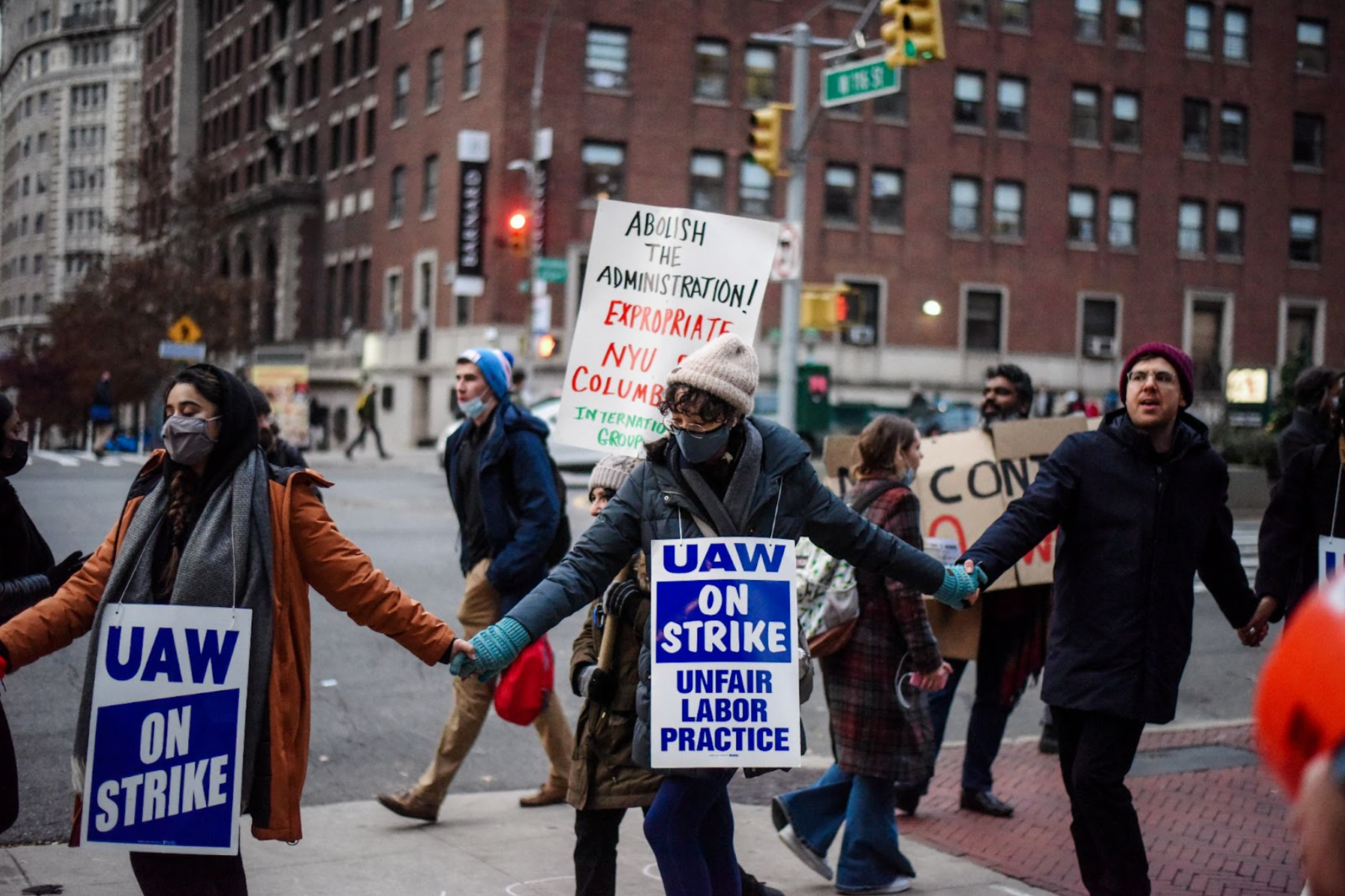

Student workers and strike supporters hold hands at the picket line. Photo by Madison Ogletree.

The Student Workers of Columbia (SWC) reached a tentative agreement with the University in the late hours of January 6 and voted to formally call off their ten-week strike the next morning. The strike—a reaction to the absence of livable wages, pay parity, health insurance, and harassment recourse, among other issues for student workers—came at a time of surging strike action across the nation. With the SWC standing more than 3,000 members strong, their strike was the largest ongoing labor action in the country for the majority of its duration. In a stunning show of labor power, the union refused to back down from its core requests during negotiations. The contract was chock full of union victories and discussed in various town halls over a period of fifteen days before a formal ratification vote was conducted from January 22 to January 27. The contract’s ratification by a 96.7 percent majority reflects the strength of student workers on campus in the face of Columbia’s egregious retaliation and represents a hard-fought victory for the national labor movement.

The University’s administration conceded to several of the strikers’ demands despite its initially staunch opposition, a testament to strikers’ resilience and patience. Access to neutral arbitration in cases of discrimination and harrasment was granted, with the caveat that in certain cases, including Title IX cases, other avenues may need to be exhausted first. This concession came seven weeks into the strike, after the University had argued for years that such a process was unfit for academic working conditions. The union, however, maintained that a third-party arbitration process was necessary for student workers because no employer—universities included—can be trusted to investigate itself. Columbia met another hard-fought demand in the strike’s tenth week: the full recognition of the bargaining unit to include both graduate student workers on a fixed stipend and casual employees like undergraduate teaching assistants. The unit thus includes all student workers who the National Labor Relations Board certified it to represent in SWC’s 2017 union election. This victory was key because the membership of the bargaining unit, unlike other terms of the contract, is difficult to renegotiate in the future.

Other highlights of the agreement include a 40 percent increase of the minimum hourly wage, a pay parity policy that will bring wage increases of as much as 30 percent to some salaried workers, a minimum 12-month salary approaching the union’s initial salary demands, and guaranteed 3 percent annual raises for the duration of the contract. Student workers who are caregivers for children too young to enroll in kindergarten will be given a child care credit of $4,500 which will increase over time. Workers will have access to a fund for out-of-pocket medical expenses that increases over time, along with two weeks of guaranteed sick leave and partially subsidized dental insurance. Hourly casual workers will also see wage increases of as much as $6 per hour with slated yearly increases. These provisions are a far cry from the prior lack of adequate wage, healthcare benefits, or recourse against harassment for thousands of Columbia’s student workers.

There remains room for even more progress in future contract negotiations. Under this contract, the administration did not fulfill the union’s demand for what the union deems a livable wage for hourly and salaried workers. Alongside pushes for further wage increases, future negotiations might also attempt to obtain protection for student workers from ICE—a demand that other student worker unions have won—and the inclusion of health care protections in the text of the contract. Negotiations for the next SWC contract will begin before May 2025.

Retaliation by the University: A Historical Pattern

These demands were not won easily. Student workers at Columbia had gone on strike three times before in an attempt to win a fair contract. This time around, Columbia repeatedly attempted to circumvent federal laws on labor protections and stifle student workers’ ability to strike. Presently, there are two open Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) complaints lodged against the University for its behavior towards student workers. The first, submitted on September 27, 2021, pertains to a compensation freeze implemented by the University: before the tentative agreement was reached, wages were frozen at the rate of the 2020-2021 school year. The second complaint, submitted on November 18, 2021, is related to changes in the stipend disbursement schedule instituted at the start of the 2021-2022 school year. Rather than disbursing a significant portion of stipends at the beginning of the semester, Columbia’s administration changed the disbursement schedule to bimonthly. This modification made it significantly more difficult for student workers to strike as they became reliant on a stream of paychecks coming from the University throughout the semester.

Both of these actions violated Section 8(a)(5) of the National Labor Relations Act as the University modified critical aspects of wages—a mandatory subject of bargaining—without negotiating with the union. They showcase Columbia’s long history of hostility towards student workers organizing, a reality that is further evidenced by the University’s refusal to negotiate with the union over the summer in preparation for the fall semester. Despite reaching the tentative agreement in 2022, Columbia has yet to respond to either of these complaints. Instead, Columbia made it a priority during negotiations to dodge legal penalties by insisting that the formal ULP complaints be dropped as a condition of the agreement.

Columbia also threatened to replace the labor of striking students if they did not return to work. On December 2, 2021, Daniel Driscoll, the Vice President of the Columbia Human Resources department, sent an email stating that the only student workers who would receive appointments for the Spring term were “(a) student officers who are currently working as shown by their attestations, (b) students who are not currently on appointment, or (c) student officers who are currently on strike but return to work by December 10, as shown by their attestation for the current pay period.” This threat was illegal considering that Columbia’s student workers could not be permanently replaced or discharged by the University for striking under the National Labor Relations Act.

Scott Schell, a University spokesperson, responded to charges of illegality by stating that Columbia had the right to replace workers impermanently, or until the end of the strike. Yet, this threat to student workers protesting in accordance with labor law made it clear that Columbia’s administration has no desire to protect labor rights. Columbia’s resistance becomes all the more jarring when one considers that the administration hired Bernard Plum to represent the University in arbitration. Plum is an attorney from Proskauer Rose—a law firm notorious for taking on union-busting cases.

Columbia’s administration still found itself sensitive to criticism despite its inarguably inadequate policies for its student workers and overt, union-busting antics. On December 18, 2021, the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board published an article detailing the union’s compensation demands and what the University currently provides. Soon after, Provost Mary C. Boyce penned a response in the WSJ distinguishing Columbia student workers from employees under a private company, such as Kellogg’s, arguing that student workers were not full-time workers and received ample compensation as is. By suggesting that Ph.D. candidates were merely students rather than student workers, Boyce attempted to undermine the legitimacy of the campaign, suggest that student workers should not be engaging in collective action to win labor rights, and justify inadequate wages.

The University’s retaliation has extended to undergraduate students. Following a rally on October 27, 2021 in which protestors gained entry to President Bollinger’s class on first amendment law, the University identified undergraduates inside of the classroom through video footage posted online. These students were sent emails stating they had violated Rule 12 and Rule 14 of the Rules of University Conduct by disrupting university activities. As a result, they were required to meet with a representative from University Life to discuss their involvement. Instead of acknowledging the protest, President Bollinger voluntarily chose to end the class early and left with the accompaniment of his personal security detail. The reaction from President Bollinger and University Life was ironic given President Bollinger’s supposed dedication to “free speech,” the very content of the course he was teaching at the moment protesters arrived. Columbia, again, resorted to defense instead of addressing the protesters’ justified grievances. The administration’s behavior shows that it is more interested in attempting to silence students who disagree with its policies than to correct the ills of the institution.

Columbia’s history of strike busting spans decades, if not centuries. In 1936, a big year for elevator operator strikes in the city, operators at Teachers College staged a strike of their own. In response, Columbia threatened to replace striking workers permanently. A Spectator article written in its wake identified the University as a member of the Realty Advisory Board, a group apparently notorious for its strikebreaking action. Ten years later, elevator and janitorial staff at Columbia-owned apartments also went on strike. The recruiting firm in charge of Columbia’s hiring both threatened to replace strikers and began hiring strikebreakers midway through the three-day strike. Fifty years later, clerical workers at Barnard undertook a months-long strike over the institution’s refusal to cover medical insurance premiums. Students who participated in sit-ins to support the strike faced unwarranted disciplinary cases, including seniors being barred from full participation in their graduation ceremonies in the name of pending investigations.

Beyond strike-busting, Columbia also has a long history of anti-union activity. In the 1940s, legislators modified New York state legislation to force Columbia to accept a union for residential facility workers. It was this union that held the aforementioned successful 1946 strike. In 1984, Columbia’s clerical workers went on strike for university acceptance of their union. Twenty years later, GSEU, the first attempted graduate student union at Columbia, went on their own strike for university acceptance. Columbia refused to bargain with student workers until the SWC—then called the Graduate Workers of Columbia—went on strike in 2018, despite the fact that the union had already been recognized by the NLRB. While Columbia has always had the option–and in some cases, the legal obligation–to voluntarily recognize unions, it has consistently chosen to oppose workers’ organizing efforts.

Strike Tactics: How SWC Won in the Face of Columbia’s Resistance

During the strike, SWC used a variety of tactics learned from prior strikes or other unions’ actions to build an effective, sustainable campaign. Each week, student workers organized physical pickets at different locations, a digital picket, delivery stoppages, and a range of teach-ins with other organizations. These efforts were accompanied by more innovative protest actions, such as the march from the Columbia Medical Center campus to the Morningside Heights campus, a week of protesting in Midtown directed towards the Columbia Board of Trustees, a picket of the yearly tree-lighting ceremony, the rally leading to a class held by President Bollinger, and a hard picket of the Morningside Heights campus on December 8, 2021. Walk-outs from class were equally encouraged to kick off the strike and rally against the University’s illegal retaliation.

Student workers and supporters march from the Columbia Medical Center campus to the Morningside Heights campus. Photo by Erick Andrade.

The union also made an intentional effort to build solidarity with a range of other groups. Columbia faculty and undergraduates each received a dedicated rally to encourage support from these populations and to thank them for their solidarity. During their hard picket, the SWC received support from unions, community organizations, and politicians across New York City, including state assemblyman Zohran Mamdani.

In addition to more traditional forms of protest, the union created initiatives to boost morale and ensure that striking workers’ needs were met. Organizers hosted social events with joyful music, including Strikechella, a series of live performances on the Morningside Heights campus, and Club Strike, an off-campus benefit concert. Those on the picket line and at rallies were encouraged to bring instruments and play them. For the first time ever, SWC organized “Pawlidarity” events where workers were asked to bring their pets along to the picket—yet another morale-boosting initiative.

SWC members held signs highlighting Columbia’s hypocrisy during picketing events and used other forms of signage across campus to bring awareness to their cause. Student workers posted anonymous testimonies along the lawns on College Walk for people to view as they passed by and drew chalk art on the ground and on the side of buildings near the picket line. This trend eventually culminated in a partnership with The Illuminator on December 20, 2021, where messages in support of the strike were projected atop Low Library.

To financially support strikers, SWC produced a robust fundraising campaign. As of January 8, 2022, the Hardship Fund raised over $350,000. The union disbursed proceeds to striking workers to cover rent and other basic necessities in the absence of University payment. To raise funds, SWC shared the hardship fund on social media, hosted a bake sale, and organized an online auction of artwork. The fund allowed workers to continue picketing even as the strike drew on for several months.

As they organized these actions, SWC’s organizers had weekly negotiation sessions with Columbia’s administration in hopes of having their key demands realized in a contract. Union members on the Bargaining Committee consistently evoked how the University was required to abide by the standards of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Columbia continually attempted to refuse recognition of all student workers covered in SWC’s NLRB certification in its negotiations. The steadfastness of both the rank-and-file members of SWC and of the Bargaining Committee ultimately resulted in the tentative contract reached in January of 2022.

How Columbia Fits Into the National Movement

Columbia’s student workers’ strike is one of the latest in a series of labor actions in academia over recent years. Student workers at some public universities have had unions for decades. However, workers at private universities only gained the right to unionize after a National Labor Relations Board’s (NLRB) 2016 ruling. This ruling, which followed the GWC’s request for a union election, over-ruled a prior decision by the NLRB in 2004 determining that graduate workers were not considered workers who were eligible to unionize.

In 2018, Brandeis University served as the catalyst for a revived academic workers movement. Their graduate student workers were the first to negotiate a contract after the NLRB ruling and won up to a 56 percent increase in workers’ compensation. Thereafter, student workers at eight other private institutions, including Tufts University, American University, the New School, and Harvard, began their fight for unionization. Over the past six years, this wave of labor organizing at private institutions has occurred in tandem with tremendous wins at public universities. By 2019, over 80,000 graduate workers across public and private institutions had unionized. That number soared to even greater heights when the University of California’s (UC) administration voluntarily recognized a student researchers’ union, a decision made immediately after 10,622 UC workers voted to strike in December of 2021.

Student worker organizing has also extended beyond graduate student workers. In the spring of 2020, faced with job loss at the beginning of the pandemic, students at Kenyon College organized virtually and formed the first student union that demanded recognition for both undergraduate and graduate student workers. Despite pushback from Kenyon College administration, which hired one of the nation’s most notorious union-busting lawyers from Jones Day, K-SWOC student organizers secured signed cards from 60 percent of student workers and are pushing to have a union election. On the heels of the Student Workers of Columbia’s success, Dartmouth student workers announced their union drive and sent a letter to their administration demanding recognition, garnering momentum amongst their student body and supporters across the country. As worker organizations grow in size and militancy, university administrations are forced to sacrifice the economic power and legal authority they had grown all too comfortable using and abusing to exploit their laborers.

Academic workers aren’t just asking for higher compensation. They’re also winning radical demands that extend beyond working conditions. In the spring of 2021, student workers at NYU ratified a contract that removed ICE and CBP from campus and prevented the university from giving either agency information about NYU community members’ immigration statuses. It also forced the recognition of NYPD as a “health and safety concern that the union can bargain over.” The win revealed the importance of using workers’ power to improve broader campus conditions.

The years-long wave of academic organizing is also a reflection of the national political atmosphere, which is charged with union action. Between 2018 and 2019, teachers across the country went on strike to advocate for increased salaries and more funding for students’ education. In October, 2021, over 10,000 John Deere workers went on strike after 35 years of dormancy. They won demands for higher wages after rejecting a poor contract offered by the corporation. In December, 2021, after striking for nine months, nurses at St. Vincent Hospital won a contract to reduce understaffing at their hospital. As essential workers in industries like education, logistics, and healthcare recognize and wield their power, they disrupt workplaces across the country until their voices are heard. This wave of militancy is a culmination of a progressive presidency, new federal policy from a liberal NLRB, and years of organizing by leftist groups that have made the labor movement their priority.

While academic organizing may seem siloed from organizing across other industries, the opposite is true: a win for workers in one workplace is a win for workers across others. Universities are some of the most powerful employers in the regions they inhabit, making their working conditions the standard for other employers. Similarly, according to some researchers, union action in one industry can create a “moral economy,” wherein all employers are obligated to recognize the rights of workers in sectors beyond the industry in which a union action occurred. In these ways, the win at Columbia is a win for both the national labor movement and for campus workers who have remained resilient in their organizing for over seven years.

Moving forward, advocates must keep the lessons learned from the movement in mind. Columbia’s egregious union-busting is not an isolated incident. Rather, it reveals a broader pattern of resistance by an administration that increasingly exploits workers. As the University’s President, Provost, and Board of Trustees lose their grip on power over Columbia’s workers, they attempt to pit student workers, faculty, and staff against each other.

Yet, over the past months, we have learned that workers will enact nothing less than lasting change when united. The militancy and success of SWC is also not an isolated incident—it is a reflection of the growing national movement for labor rights that we must support. The struggle at Columbia and across the country is far from over: all workers, student and non-student alike, can win even greater change so long as we commit to fighting alongside one another.

Arpita Kanrar is a sophomore in Columbia College studying physics.

Pooja Patel is a junior in the Dual BA program between Columbia University and Sciences Po studying political science and philosophy.

Leena Yumeen is a junior in Columbia College studying political science and a member of Columbia and Barnard’s Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA) chapter.