Theorizing the Rogue State's Cultural Hegemony: An Analysis of Post-Cold War U.S. Foreign Policy

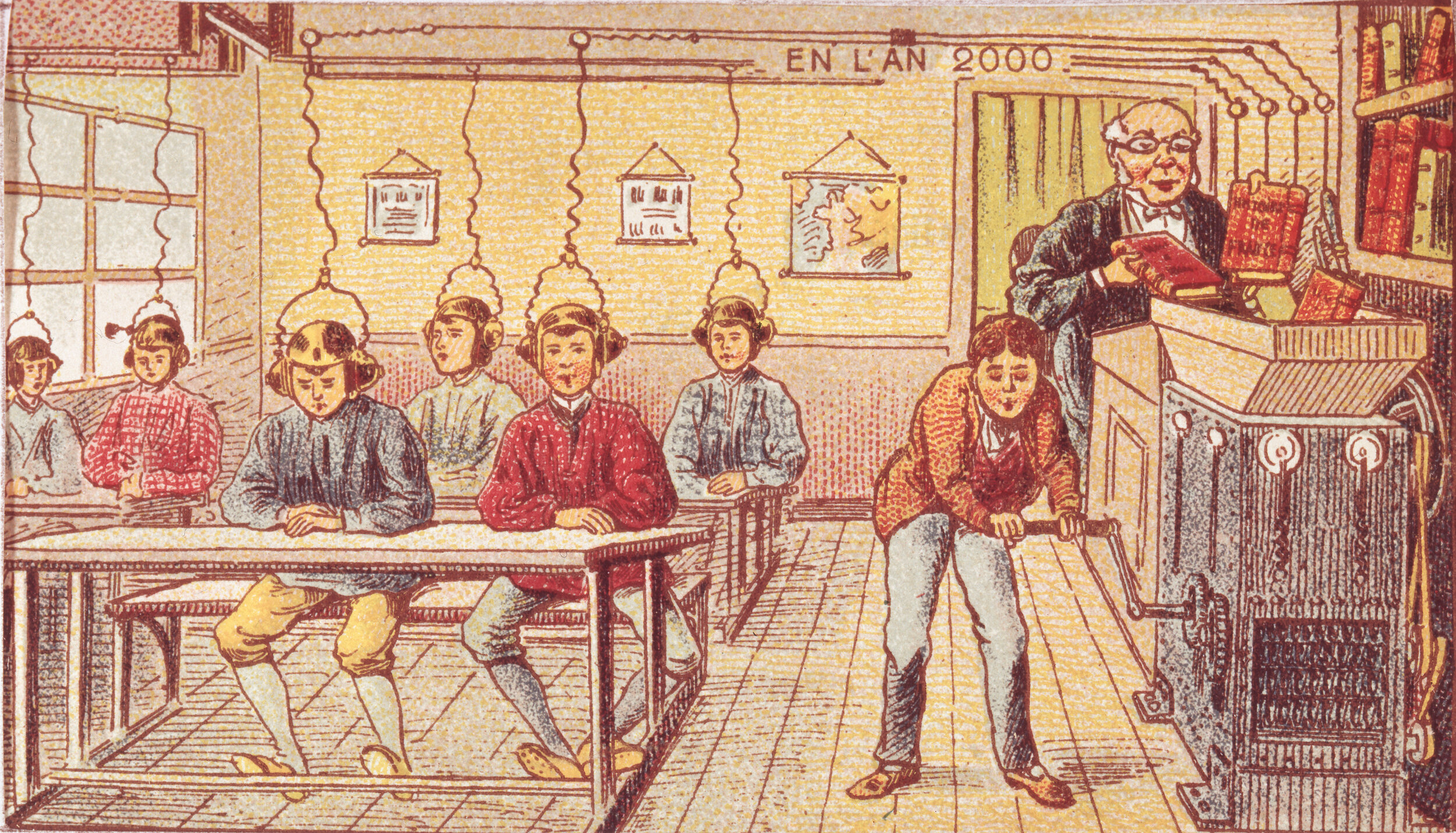

The “En L’An 2000,” or “Life in Year 2000” by Jean-Marc Côté depicts the futuristic culturization of humanity. Photo by Wikimedia France.

As American democracy saw agential depletion over the past decade, scholars like Noam Chomsky pointed to the backlash the United States would face prospectively. The reason they cited for this prediction was the United States’ overman instincts of egotism and creation of self-prophesied value systems, something Nietzsche candidly captured in his “Last Man.” In such an anarchic setting, in which there is no world government or sovereign power exerting authority over all nation-states, the United States has established hegemony to exercise sovereignty over the affairs of others. The United States’ egoism promotes a power-driven dynamic globally, and its actions have influenced other states to take up a similar Last Man view as their diplomatic outlook—Russia has annexed Crimea, China has doused Thailand’s autonomy, the Indo-Pacific has been ravaged with conflicts, and other events of such candor no longer remain black swans.

When considered collectively, Foucault and Chomsky’s theories provide a didactic and interpretive narrative to describe the hegemonic tendencies that have dominated Post-Cold War international politics. The two philosophers critique the Westphalian world order, which has overseen the tides of political change all too long. Today, this world order best fits a neo-realist framework, which also acknowledges that anarchic power struggles defined by state egoism have the tendency to swivel out of control. Since the end of the Cold War, such "control" has been maintained by the United States, but lately the nation has steered the ship of the American Foreign Policy into the torrential waters of volatile relations and failures in diplomatic quid pro quo. Indeed, its expansionism continues and has made peace a radical concept in the 21st century, an example being the nuclear race between India and Pakistan which stops war only to proliferate more fear in the two nations. Order, thus, must be established to ensure that the diplomatic failures of one state in the realpolitik do not force other nation-states into a difficult position.

AN ANALYSIS OF U.S. FOREIGN POLICY USING THE CHOMSKYAN ROGUE & SAID’S DISCURSIVE STUDY

In his book Rogue States, Chomsky polemically calls out the bedrock of U.S. Foreign Policy on its ultra-realism, or its excessive self-centered focus, which is hidden beneath the veneer of the puddled idealistic principles of safeguarding human rights and democracy overseas. He builds a framework to delineate the “rogue-ness” of the United States, a term that was popularized after the Cold War to describe states which used terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, and despotism as instruments of power politics in their respective nations and regions. The U.S. State Department designated Iraq, Iran, North Korea, Libya, Indonesia, Vietnam, Kosova, Colombia, and Croatia as the primary "rogue states.” The United States used arguments of moral superiority to pursue scorching military and political intervention in these countries and beyond, oftentimes prompting war and instability. In doing so, the United States ignored, bashed, and battled various resolutions of the United Nations, disregarding international law and norms to gain leverage within the aforementioned countries, such as the support provided to General Suharto for the murderous continuation of Operation Clean Sweep in East Timor.

While the United States typically deemed countries in the East “rogue states,” Chomsky turned the tables, called out the Eagle's policy goals, and termed the United States the rogue one. With the realist intention of perforating its interests, the United States leveraged the cultural hegemony it had established through McDonaldization and westernized discourse of democratism and liberalism while asserting moral superiority across the spectrum. Knowing the reactions such imposition would prompt, the West fostered a narrative that the Oriental world was backward, lacking organic intelligentsia or a civilized construct of society. In 1978, Edward W. Said contested the eponymous description of “The East” and the cultural representations that Western nations attached to it. His analysis reveals how Western thought has tried to mirror constructed inferiority at the lands of Aladdin. Employing a Gramscian approach, he portrayed the arbitrariness with which Western versions of the East have categorically come to dominate political thought, and he described the East’s internalization of its depiction as the non-progressive, fanatically dogmatic, irrational side of the world. The United States disproportionately benefited from the East's internalization of this narrative.

However, the United States’ assertion of moral superiority was merely the first step in establishing its legitimacy in international realpolitik. Subsequently, the United States bestowed Kissingerian legitimacy upon only those states which it considered deserving of existence, a strategic gunpoint it used for decades. In addition to this, it has manipulated Weberian legitimacy—or, as sociologist Max Weber called it, used legitimalaise—in order to ensure that its power and might can sufficiently tilt the balance of power in any region across the world, examples of which include the United States’ interference in Indonesian politics in 1965. Dominating the seas, the lands, the world culture, and thus, the minds of people, the U.S. government used its power to nurture animosities that spiraled out of hand one after another.

The United States also installed inferiority into the discourse about the East to further its own economic interests. This manufactured inferiority was injected by the West into cultures of only a select basket of nation-states using constructed narratives like the “American Dream” as superior alternatives to the so-called traditional lifestyles that dominated the East. Such nation-states were primarily those which had black gold in their womb—oil, large markets, and all that America needed to raise its profits above its glass ceiling. As Chomsky outlines in his Propaganda Model, a wave of vetocracy spearheaded by large corporations painted the canvas of foreign policy. This strategy helped the United States install puppet regimes across the Middle East, which reinforced its discourse-based subjugation of these regions, elicited economic benefits out of the mineral and oil-rich lands, and dethroned Russia's hold throughout Asia.

MAINTAINING THE ‘SAVIOR’ THROUGH FOUCAULDIAN CULTURAL PRODUCTION

Mainstream media in the United States either calculatively ignored these gruesome interventions in the East or portrayed them in a good light. The portrayal of the United States as the “Savior” prevented its policymakers from facing adverse national public opinion for their disastrous foreign policy. This carefully engineered, mutually-beneficial interface among political leaders, businessmen, and other middlemen built a superstructure that continues to dominate popular understanding in the United States even today. This quid pro quo among various groups caused the internal agential decay of the only superpower that positioned itself at the pinnacle of the world order.

The United States choreographed moral superiority over the psyches of about five billion peoples, reflecting a Foucauldian power hierarchy with legitimation and ‘regimes of truth’ patenting the ‘common sense' of the masses. According to author and activist Naomi Klein, discourses constructed using Hollywood movies, portrayals of the Californian lifestyle, and so on fuel the legitimacy that politically conducive conceptions are able to gain. As such legitimacy is advanced, it eventually turns into truth, the length of time taken depending upon the severity of discourses that are set into force. Over time, the manufactured truth travels from the upper notches of the intelligentsia to the layman. In this way, cultural power is produced by the hegemon. Such power embraces social, political, and economic functioning and behavior, which eliminates any chance of unfavorable reaction by the masses unless this reaction is propelled by an organic and vehement deconstruction of the discourse thus accepted as truth. The West installed this Foucauldian discursive practice into the annals of the East's history. From Western education to economics, the Western discourse ignored the natural glory of the East to benefit its perceptions and economic interests. Nietzche would be proud of this Superman, if not for long.

Attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City, in 1993 and 2001, were the diabolical reactions that many scholars see as a consequence of the depletion of the superiority the West had tried to coerce upon the East. In the article De-Facing Power, C.R. Hayward suggested that extremism resulted from the West's constant tampering of the cultural contingencies of the East. These consequences reveal the need to review the current realpolitik of the anarchic international order.

PROGRESSION TOWARDS THE NON-PROGRESSIVE

The rogue-ness of the United States’ foreign policy for its self-indulgent interests in the vetocracy remains. In the 21st century, the so-called “Clash of Civilizations” has transformed into a clash of cultures. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict, which has been deepened beyond measure by Western and now Chinese interference, exemplifies this clash. Meanwhile, the United States’ rogue-ness has been diminished by its excessive economic dependence on intertwined global supply chains that dominate the neoliberal world order, and the nation faces a challenge from the rising economic power of China. The rise in nationalism across the globe hides the element of cultural protection and security that have started dominating popular culture. China and Iran, for example, have claimed superiority over other cultures different from theirs, and the future holds the answer to their whims. Perhaps the new Rogues hold a better tomorrow in store.

Zinnia Aurora is an undergraduate student at University of Delhi (St. Stephen’s College ’22) pursuing a double major in Economics and Political Science. She can be reached at zinniaaurora7@gmail.com.