Organization of American States or Ministry of American Colonies?

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (left) and O.A.S. Secretary General Luis Almagro (right). Photo by Freddie Everett.

“The United States has sought from the inter-American system 'the legitimacy of multilateralism’, or, to put it more simply, an O.A.S. label for her hemispheric policies.”

– Gordon Connell-Smith, 1965

On January 17th of this year, Secretary of State and former C.I.A. director Mike Pompeo delivered a speech to the Organization of American States, hailing the 72-year-old intergovernmental body’s “Multilateralism That Works.” After thanking the organization’s leadership and the United States ambassador to the body, Pompeo took a moment to recognize the O.A.S.’s roots in American political history:

“I’m reminded as I stand in front of this beautiful array of people and in this gorgeous place—I’m reminded that it was an American Secretary of State, a man named James Blaine, who first advocated for a closer union of the American states in the late 19th century. It was his vision that would become this institution, the O.A.S., in 1948.”

Pompeo then proceeded without discussing who James Blaine was or what his vision for “a closer union of the American states” actually entailed. Examining this legacy is vital not only for understanding the purpose of the O.A.S., but also for placing the Organization in the broader context of U.S. foreign policy.

Building an Empire

Before serving as Secretary of State under three different presidents, James Blaine was also a member of the United States Senate for five years, Speaker of the House for six years, a three-time presidential candidate, and one of the founders of the modern Republican party. His views on the world and the role of the United States are captured in a statement he made at the end of the 19th century:

“I think there are only three places that are of value enough to be taken… One is Hawaii and the others are Cuba and Porto Rico [sic]. Cuba and Porto Rico are not now imminent and will not be for a generation. Hawaii may come up for decision at an unexpected hour and I hope we shall be prepared to decide it in the affirmative.”

– James Blaine, 1891

The Census Bureau announced the “closing of the frontier” in 1890, and the desire for continued territorial and economic expansion turned the eyes of the U.S. from the West toward the South. James Blaine’s vision for the conquest of these nations, rich in natural resources and cheap labor to exploit, represented the foundation of a new era of occupation and dispossession.

Following the 1893 coup d’etat against Queen Lili’uokalani by American and European citizens living in Hawai’i, U.S. Marines were deployed to the island to secure the “provisional government” established by the settlers. The leader of the coup was Sanford Dole, a cousin of James Dole, the founder of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company which would later become known as Dole Pineapple. When Hawai’i was annexed to the United States in 1898, a journal run by American plantation owners declared Hawaii “The First Outpost of a Greater America.”

That same year, the United States entered into the Spanish-American War following diplomatic tension over the situation in Cuba. Largely aided by “yellow journalism” and calls to “Remember the Maine!”, this conflict would cement the United States’ imperial ambitions in the Americas and beyond. Noam Chomsky’s 1998 essay on the legacy of the Spanish-American War, “A Century Later,” provides essential context to the United States invasion of Cuba:

“Seventy years earlier, John Quincy Adams had described Cuba as a ‘ripe fruit’ that would fall into U.S. hands once the British deterrent was removed. By 1898, Cubans had effectively won their war of liberation against Spain, threatening ‘more than colonial rule and traditional property relations,’ historian Louis Perez notes, adding that ‘Cubans also endangered the United States’ aspiration to sovereignty.’ Cuban independence had been ‘anathema to all North American policymakers since Thomas Jefferson.’”

– Noam Chomsky, 1998

Rather than creating an authentically independent Cuban state, the invasion ensured that Cuba would merely transition from being a Spanish colony to being an American one—a colonial relationship that would persist until the Cuban Revolution of 1959. The same fate awaited Puerto Rico, which, as Chomsky notes, “was turned into a plantation for U.S. agribusiness, later an export platform for taxpayer-subsidized U.S. corporations, and the site of major U.S. military bases and petroleum refineries.”

Following the cession of the Philippines by Spain in 1899, Filipino independence fighters led by Emilio Aguinaldo fought against American occupation forces in a war that would result in the deaths of 200,000 Filipino civilians, 24,000 Filipino combatants, and 4,200 Americans. According to the U.S. State Department,

“U.S. forces at times burned villages, implemented civilian reconcentration policies, and employed torture on suspected guerrillas, while Filipino fighters also tortured and captured soldiers and terrorized civilians who cooperated with American forces. Many civilians died during the conflict as a result of the fighting, cholera and malaria epidemics, and food shortages caused by several agricultural catastrophes.”

Cartoon in Puck Magazine depicting racist caricatures of the Philippines, Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, and Cuba being taught “Civilization” by Uncle Sam, along with racist depictions of African-Americans, Asian-Americans, and Indigenous people, 1899. Cartoon by Louis Dalrymple.

The taking of these “ripe fruits” was a major harbinger of the United States’ continental ambitions. In the following decades, Presidents McKinley, Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson took turns doing their part to extend “gunboat diplomacy” across the hemisphere. Subsequent military interventions in Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Mexico, Panama, and Honduras revealed the extent to which Washington would go to project power over its so-called “backyard.” Reflecting on the first occupation of Haiti by the United States, Edwidge Danticat writes,

“One of the stories my grandfather's oldest son, my uncle Joseph, used to tell was of watching a group of young Marines kicking around a man’s decapitated head in an effort to frighten the rebels in their area… Of the time U.S. Marines assassinated one of the occupation’s most famous fighters, Charlemagne Péralte, and pinned his body to a door, where it was left to rot in the sun for days… During the nineteen years of the U.S. occupation, fifteen thousand Haitians were killed.”

– Edwidge Danticat, 2015

In a 1935 article written for Common Sense, Smedley Butler, who was the most decorated United States Marine in history when he passed in 1940, reflected on his own role leading military interventions in Latin America and elsewhere:

“I spent 33 years and four months in active service as a member of our country's most agile military force—the Marine Corps. I served in all commissioned ranks from a second lieutenant to a major general. And during that period I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street, and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism… Thus I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914, I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in… I helped purify Nicaragua for the international banking house of Brown Brothers in 1909–12. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for American sugar interests in 1916… During those years I had, as the boys in the back room would say, a swell racket. I was rewarded with honors, medals, promotion. Looking back on it, I feel I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three city districts. We Marines operated on three continents.”

– Smedley Butler, 1935

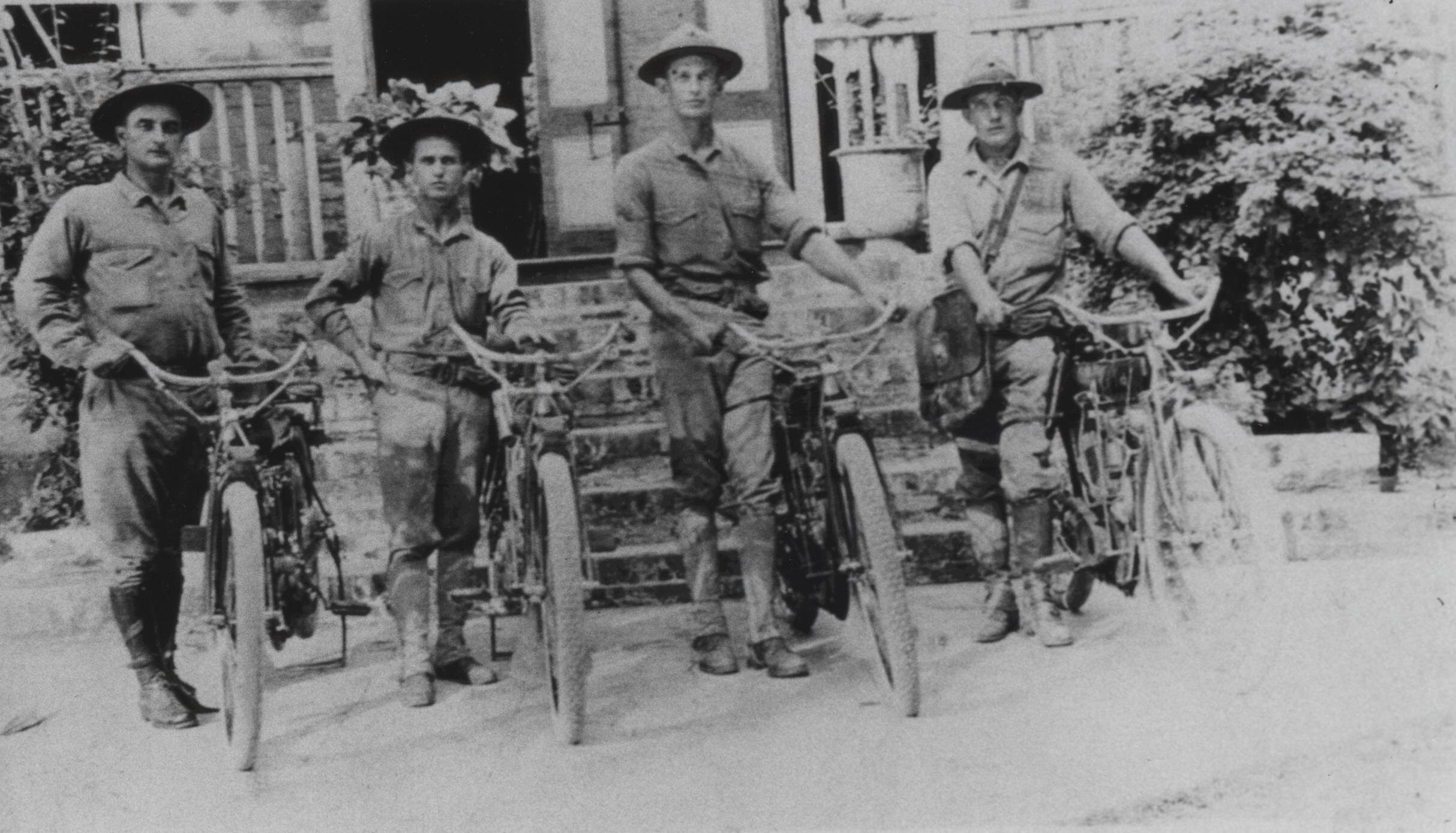

U.S. Marines stationed in Haiti pose with motorcycles, circa 1915. Photo from the U.S.M.C. Archives.

U.S. Marines pose with the captured flag of Nicaraguan revolutionary Augusto Sandino, 1935. Photo from the U.S.M.C. Archives.

Cold Warriors

This was the legacy inherited by the Organization of American States in 1948. With the end of World War II and the emergence of the United States as a hegemonic power in the West, there was a renewed call to assert U.S. dominance in the hemisphere for matters of both economic need and regional security. In response to the Soviet Union emerging as an industrial and military power after the war, U.S. diplomat George F. Kennan produced two major documents, the “Long Telegram” in 1946 and “Sources of Soviet Conduct” in 1947 (also known as the “X Article” due to his writing it under the pseudonym “Mr. X”). Kennan advocated for a hard-line strategy of anti-Communism and containment due to what he saw as the inherently expansionist nature of the Soviet Union. His vision informed what would become known as the “Truman Doctrine,” governing American foreign policy for years to come. In the “X Article,” Kennan writes,

“[The Soviets’] particular brand of fanaticism, unmodified by any of the Anglo-Saxon traditions of compromise, was too fierce and too jealous to envisage any permanent sharing of power. From the Russian-Asiatic world out of which they had emerged they carried with them a skepticism as to the possibilities of permanent and peaceful coexistence of rival forces.”

“The issue of Soviet-American relations is in essence a test of the overall worth of the United States as a nation among nations. To avoid destruction the United States need only measure up to its own best traditions and prove itself worthy of preservation as a great nation.”

– George F. Kennan, 1947

Written just a year prior to the establishment of the O.A.S., Kennan’s words provide insight into how the United States evolved in its attempts to project power internationally. U.S. domination of the hemisphere was no longer a matter of “protecting commercial interests” or conquering valuable territory; it was now both an existential imperative and a national test. Having affirmed that peaceful coexistence with the Soviet Union and its allies was not on the table, the stated goal of U.S. foreign policy was to ensure the containment of “Communism” at any cost and to promote the expansion of “democracy and freedom” under U.S. leadership. The era of struggle with the old empires of Europe was dead and the so-called “Cold War” era had begun.

Following the signing of the Rio Pact in 1947, the 19th-century International Union of American Republics was transformed into a military alliance. This new group would then expand to include economic, social, and political matters, becoming the O.A.S. we know today. From its Charter, the stated goals of the O.A.S. are as follows:

To strengthen the peace and security of the continent;

To promote and consolidate representative democracy, with due respect for the principle of nonintervention;

To prevent possible causes of difficulties and to ensure the pacific settlement of disputes that may arise among the Member States;

To provide for common action on the part of those States in the event of aggression;

To seek the solution of political, juridical, and economic problems that may arise among them;

To promote, by cooperative action, their economic, social, and cultural development;

To eradicate extreme poverty, which constitutes an obstacle to the full democratic development of the peoples of the hemisphere; and

To achieve an effective limitation of conventional weapons that will make it possible to devote the largest amount of resources to the economic and social development of the Member States.

These purposes have remained largely unchanged throughout the O.A.S.’s 72-year history. As Peter J. Meyer wrote for the Congressional Research Service in 2018, “Today, the O.A.S. concentrates on four broad objectives: democracy promotion, human rights protection, economic and social development, and regional security cooperation… The United States is the largest financial contributor to the O.A.S., providing an estimated $68 million in FY2017—equivalent to 44% of the organization’s total budget.” By nature of this financial relationship, the O.A.S.’s commitment to these goals tends to vary depending on the United States’ relationship to the conflict at hand.

Secretary Pompeo provides his own reflection on the history of the O.A.S. in the 20th century:

“These have been landmark actions, and in taking these actions we’re returning to the spirit the O.A.S. showed in the 1950s and 1960s. We sent election monitors to Costa Rica in 1962. Two years later, we imposed sanctions on Cuba for attempting to overthrow the democratically elected Government of Venezuela by force.”

It did not take very long for the principles of “democracy” and “human rights” promoted by the O.A.S. to come into conflict with the foreign policy interests of the United States. In “The O.A.S. and the Dominican Crisis”, written at the time of the invasion of the Dominican Republic by the Marines, Gordon Connell-Smith provides a look at the development of this relationship:

“At the Tenth Inter-American Conference (Caracas, 1954), the United States endeavoured to obtain Latin American agreement to the proposition that: ‘the domination or control of the political institutions of any American State by the international communist movement, extending to this hemisphere the political system of an extra-continental power, would constitute a threat to the sovereignty and political independence of the American States, endangering the peace of America, and would call for appropriate action in accordance with existing treaties.’ This was, in effect, an endorsement of the Monroe Doctrine, which would be violated by the mere existence of a communist government in the Western hemisphere. The Latin Americans were not prepared to accept this, and most of them supported a modified version only with reluctance and in the face of great pressure; warm support came only from right-wing dictatorships. Argentina and Mexico did not vote for the Caracas anti-communist resolution; Guatemala, against whose government it was directed, opposed it.”

– Gordon Connell-Smith, 1965

Later that same year, the democratically-elected government of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala was overthrown in a military coup greenlit by President Eisenhower and supported by the C.I.A., ushering in an era of right-wing dictatorships that would last until 1985. The ensuing 36-year Civil War, fought between succeeding military regimes and left-wing guerilla groups, would claim the lives of 200,000 civilians, almost entirely at the hands of the state.

In 1960, following the overthrow of U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista and Cuba’s alignment with the Soviet Union, the Eisenhower administration failed to secure a condemnation of the Cuban government from the Seventh Meeting of Consultation of American Foreign Ministers when they met to discuss Communist activity in the hemisphere. As a result of this failure, the succeeding Kennedy administration supported an attempted invasion of the island organized by the C.I.A. and Cuban exiles, who were primarily trained in Guatemala, in 1961:

“‘Guatemala was the model,’ Michael Warner wrote in the C.I.A.'s historical analysis of the invasion. ‘In Guatemala in 1954 headquarters all but lost hope that the C.I.A.-trained invading force could overthrow the leftist government of Jacob Arbenez, when suddenly the Guatemalan army turned on Arbenz who stepped down and fled.’

The Bay of Pigs was not Guatemala.”

Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces counter-attack at Playa Giron during the Bay of Pigs invasion, 19 April 1961. Photo by unknown.

Another major shift occurred in 1963 when the government of Juan Bosch, who had won almost 60% of the vote in the Dominican Republic’s first free elections in more than 30 years, was also overthrown by a military coup supported by the Central Intelligence Agency. After a mass uprising in 1965 defeated the military junta and attempted to restore Bosch’s presidency and the 1963 Constitution, President Lyndon Johnson ordered the invasion of Santo Domingo, which led to a military occupation and the establishment of a “provisional government.” This series of events would allow Joaquín Balaguer, a right-wing collaborator of Rafael Trujillo’s dictatorial government (which had also been supported by the United States), to establish his own authoritarian regime which would murder and imprison thousands of dissidents. Perhaps most significantly, as noted by Connell-Smith,

“This was the first time the United States had taken such action since Franklin Roosevelt launched the Good Neighbour policy in 1933. Moreover, it was in clear violation of the O.A.S. charter which declares that the territory of an American State 'may not be the object, even temporarily, of military occupation or of other measures of force taken by another State, directly or indirectly, on any grounds whatever’ (Article 17).”

– Gordon Connell-Smith, 1965

General Caamaño (left) and the “Constitucionalistas” march through the streets of Santo Domingo during the Revolution of 1965. Photo by unknown.

The United States was able to maintain control over the situation and secured a two-thirds majority vote from the O.A.S. to create an “inter-American peacekeeping force” on the island, despite protests from several Latin American governments and international condemnation. It was now clear that the “inter-American system” and its democratic principles only applied when and where Washington wanted them to.

In 1964, the United States would support another coup against the democratically-elected government of Joao Goulart in Brazil, which led to Brazil severing diplomatic ties with Cuba and the creation of a brutal military dictatorship which would stay in power until 1985.

This is the spirit of the O.A.S. which Mike Pompeo wistfully recalls. His summary of the O.A.S.’s history continues:

“But sadly, the O.A.S. drifted in the 1970s and 1980s. Military dictatorships in our hemisphere colluded to prevent concerted action to support freedom. Some Latin American countries were still in the thrall to leftist ideas that produced repression for their own kind at home and stagnation in this building. And even in the early part of this century, with the O.A.S., many nations were more concerned with building consensus with authoritarians than actually solving problems.”

Pompeo’s assertions run contrary to the reality of U.S. foreign policy during this time. The 1970s and 1980s coincided with what some consider to be the darkest years of United States involvement in Latin American affairs. Operation Condor, the Contra War, and the Salvadoran Civil War represent some of the most gruesome examples of the United States-sponsored violence that took place during this time period. Although Pompeo seems to regret the “collusion” of “military dictatorships” as an obstacle to “freedom”, he also seems to forget that the very institution he used to direct, the C.I.A., was instrumental in bringing most of those dictatorships into power and the government which he currently represents eagerly collaborated with these dictatorships as a matter of “regional security”—thwarting dangerous “leftist ideas”, by force if necessary.

Operation Condor was a program of regional cooperation between the authoritarian military governments of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay under the direction and aid of the United States government and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in particular. Through this program, these governments shared intelligence and assisted one another in the torture, murder, surveillance, and overall repression of political dissidents.

One of America’s key allies in Latin America at this time was General Augusto Pinochet, the military dictator of Chile who had carried out a 1973 coup against the government of Salvador Allende. Allende was a Socialist who had carried out the nationalization of several industries and allied himself with other left-wing forces, leading the Nixon administration to view him as a threat to the United States’ interests. Even before the coup, the U.S. government actively undermined Chilean democracy to prevent him from taking office:

“For example, our government intervened massively to prevent Allende from winning the preceding election, in 1964. In fact, when the Church Committee investigated years later, they discovered that the U.S. spent more money per capita to get the candidate it favored elected in Chile in 1964 than was spent by both candidates (Johnson and Goldwater) in the 1964 election in the U.S.!

Similar measures were undertaken in 1970 to try to prevent a free and democratic election. There was a huge amount of black propaganda about how if Allende won, mothers would be sending their children off to Russia to become slaves—stuff like that. The U.S. also threatened to destroy the economy, which it could—and did—do.”

– Noam Chomsky, 1994

Despite their best efforts, Allende won the election and formed a government. He called for the redistribution of wealth, nationalized Chile’s mineral wealth, and instituted programs to curb malnutrition and poverty. Allende’s government captured the spirit of Chile’s working class and brought it into the halls of power. This was, of course, unacceptable. Nixon declared they would “make the economy scream” and immediately began to plot against the Chilean government with the help of the C.I.A. and the State Department.

Supporters of Salvador Allende rally in Santiago, Chile, 1964. Photo by James N. Wallace.

Within two years of the coup, Pinochet’s junta had “wiped out 30,000 of the population, imprisoned another 200,000 and left 22,000 widows and 66,000 orphans.”

In 1976, well-known Chilean dissident, former diplomat, and former political prisoner Orlando Letelier was assassinated, in broad daylight, by a car bomb in Washington, D.C.

“The U.S. government knew, as the result of a report written by the C.I.A. in 1978, that Pinochet had been not only aware of the murder but had ordered the murder. And nothing was said or done in this respect during all these years, particularly when Pinochet was alive.”

– Juan Gabriel Valdés, former Chilean ambassador to the United States and assistant to Orlando Letelier at the Institute for Policy Studies, 2016

An act of terrorism against a resident of the United States, sponsored by a government installed by and allied with the United States, had taken place in the nation’s capital.

Earlier that year, Pinochet addressed the Organization of American States:

“[Pinochet] called on Latin America today to stand cohesively with the United States in an ‘ideological war’ against Communism.

Citing the ‘armed expansionism’ of what he termed Soviet imperialism, General Pinochet said at a meeting of hemisphere foreign ministers here that ‘there is no room for comfortable neutralism’ in the Americas, and he scoffed at peaceful coexistence.

The 60-year-old Chilean ruler, wearing his blue-gray general's uniform and flanked by an aide, accused Cuba and Mexico of violating the principle of nonintervention in the internal affairs of another American country.”

– Juan de Onís, 1976

Pinochet’s comments reflect both a stunning lack of self-awareness as well as a look at the underlying reality of United States involvement in Latin America. This is what the Truman Doctrine wrought: the justification of mass violence and repression for the sake of maintaining a paranoid posture of “anti-Communism.” Pinochet’s call for continued allegiance to the United States while simultaneously accusing the governments of Cuba and Mexico of “violating the principle of nonintervention”—knowing that his own position was heavily dependent on United States involvement in Chilean affairs—reveals the fundamental hypocrisy and cynicism of this relationship.

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (center) and General Augusto Pinochet (right), 1976. Photo by Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile.

Similar crimes were committed by the other “Operation Condor” governments. Two years before the coup in Chile, U.S. intelligence agencies financed and supported another military coup in Bolivia. They would bring the new regime of Hugo Banzer into contact with Nazi war criminal and “Butcher of Lyon” Klaus Barbie, who acted as a torturer for the regime and helped orchestrate the murder of civilian dissidents. After the 1976 military coup in Argentina, Kissinger told the foreign minister of far-right dictator Jorge Rafael Videla: “We want you to succeed. We do not want to harass you. I will do what I can.” The military dictatorship would be responsible for the “disappearance” of more than 30,000 civilians who were tortured to death, thrown out of airplanes, and machine-gunned at the edges of mass graves. This terror was spread throughout South America by the United States and right-wing collaborators, and the O.A.S. did nothing to impede the widespread violation of the human and political rights of Latin Americans. Overall, Operation Condor is estimated to have claimed between 60,000 and 80,000 victims.

In the 1980s, the United States backed right-wing death squads throughout Central America, many trained at the infamous School of the Americas (now known as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation or WHINSEC):

“On September 20, 1996, under intense public scrutiny, the Pentagon released the S.O.A. training manuals, which advocated torture, extortion, blackmail, and the targeting of civilian populations. The release of these manuals proved that U.S. taxpayer money was used to teach Latin American state forces how to torture and repress civilian populations.”

Banzer and Videla were also School of the Americas alumni.

In Nicaragua, the C.I.A. armed and financed the “Contras”, right-wing paramilitaries fighting against the left-wing Sandinista government, named for anti-occupation revolutionary Augusto Sandino, which had overthrown U.S.-backed dictator Anastasio Somoza in 1979. As a member of the Reagan administration, Oliver North actively worked with cocaine traffickers to secure financial support for the Contras, who would become notorious for widespread human rights abuses and massacres. When the International Court of Justice ruled that the United States should pay reparations to Nicaragua for its support of the Contras, the United States refused to acknowledge the ruling and called the Sandinista government a “Soviet puppet.”

Sandinista fighters of the “Sócrates Sandino” Irregular Combat Battalion during the Contra War. Photo by Stephanos Westgoten.

Elliot Abrams, another major Reagan official and proponent of “Hemispherism,” fiercely defended U.S. policy supporting the right-wing government of El Salvador in its war against the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (F.M.L.N.), a left-wing guerilla organization named after the Marxist-Leninist peasant revolutionary. A UN report later concluded that, “of 22,000 reports of human rights abuses (including extrajudicial killings, disappearances and torture) committed during the twelve-year civil war, 85% were perpetrated by the U.S.-backed state forces.” The military was also responsible for the murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was recently canonized by the Catholic Church.

In 1982, General Efraín Ríos Montt, another School of the Americas alumnus who had participated in the 1954 coup against Jacobo Arbenz, took power in Guatemala via yet another military coup. As Ríos Montt carried out a campaign of violence against Ladino peasants, Indigenous Maya communities, and suspected leftist guerillas, President Reagan argued he was “getting a bum rap on human rights...I know that President Ríos Montt is a man of great personal integrity and commitment...I know he wants to improve the quality of life for all Guatemalans and to promote social justice. My administration will do all it can to support his progressive efforts.” Ríos Montt was sentenced to 80 years in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity in 2013.

In 1983, after the assassination of left-wing Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, the United States military invaded Grenada and bombed a mental hospital, killing 12 civilians.

In 1989, the United States invaded Panama to oust former C.I.A. asset and drug trafficker Manuel Noriega from power. The Commission for the Defense of Human Rights in Central America estimates between 2,500 and 3,000 people died in the process.

Turn of the Tide

Luckily, Secretary Pompeo notes, all of this came to an end in the 1990s:

“But the good news is—and I’m so proud of what you all have accomplished—that’s all changed. Yes, we enjoyed a resurgence of the democratic values in the ‘90s. But these days—more than ever—our values drive actions that support a hemisphere of freedom.”

Pompeo is partially correct. In 1994, the Clinton administration carried out another invasion of Haiti under the name “Operation Uphold Democracy” to reinstall the elected government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide after it had been toppled by a military coup. However, as Chomsky notes, “It was overlooked that the restoration was conditional on acceptance of the socioeconomic programs of the U.S.-backed candidate in the 1989 elections, who had received just 14% of the vote. State Department spokesperson Strobe Talbott assured Congress that after U.S. troops left Haiti, ‘we will remain in charge by means of USAID [United States Agency for International Development] and the private sector.’” In 2004, another coup was launched against Aristide. CNN reported that “[Congresswoman Maxine] Waters said that Aristide told her the chief of staff of the U.S. Embassy in Haiti came to his home, told him that he would be killed ‘and a lot of Haitians would be killed’ if he did not leave and said he ‘has to go now.’”

The Pink Tide of the 2000s would usher in yet another period of conflict between the United States and the left throughout Latin America. Starting with the election of Hugo Chávez as President of Venezuela in 1998, the left would soon take power through elections in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, Nicaragua, Peru, Haiti, Honduras, and Paraguay, presenting a major threat to the neoliberal “Washington Consensus” that had been established in the 1990s.

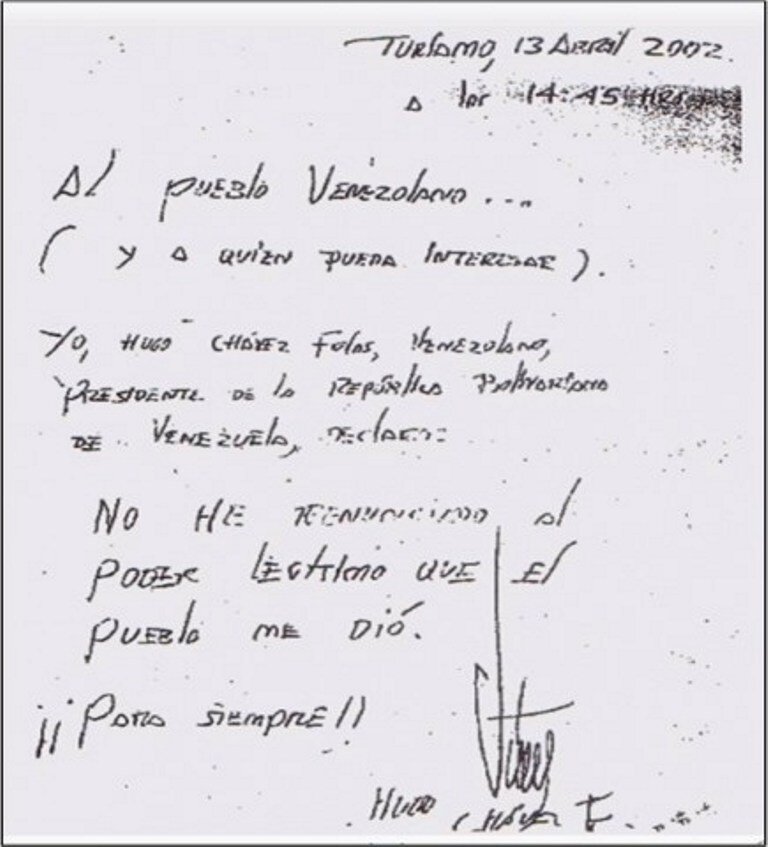

In 2002, the Bush administration supported an attempted coup against the democratically-elected government of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. The officials implicated were mostly familiar faces. According to The Guardian’s reporting on the coup, “all of [them] owe their careers to serving in the dirty wars under President Reagan.” Elliot Abrams was implicated once more, alongside Otto Reich, who had reported directly to Oliver North while serving under the Reagan administration and had been appointed U.S. ambassador to Venezuela in 1986. Abrams himself was the “crucial figure around the coup” and had been serving as “senior director of the National Security Council for ‘democracy, human rights and international operations’.” U.S. ambassador to the UN John Negroponte was also implicated in the coup. Negroponte, “was Reagan's ambassador to Honduras from 1981 to 1985 when a U.S.-trained death squad, Battalion 3-16, tortured and murdered scores of activists.” The coup against Chávez would ultimately fail as his supporters in the streets and in the military successfully retook the Presidential Palace, but it set the stage for wider conflict over the future of the hemisphere and contributed to the further radicalization of the Bolivarian left.

Letter from President Hugo Chávez to the Venezuelan people stating that he did not resign the presidency, 13 April 2002.

Text: “To the people of Venezuela...(and whoever else may be interested), I, Hugo Chávez Frías, Venezuelan, President of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, declare: I have not resigned the legitimate power that the people gave me. Forever! Hugo Chávez Frías”

As other left-wing governments set out to chart an alternative path for regional integration, free from dependency on the United States and its interests, they also came into conflict with Washington. One such example came in 2005, when a bloc of left-wing Latin American governments including Chavez as well as Presidents Evo Morales of Bolivia, Lula da Silva of Brazil, and Nestor Kirchner of Argentina defeated the Free Trade Area of the Americas, a major trade initiative of the Bush administration which would have created the largest free trade area in the world. Morales called the F.T.A.A. “an agreement to legalize the colonization of the Americas.”

Left to right: Presidents Fernando Lugo of Paraguay, Evo Morales of Bolivia, Lula da Silva of Brazil, Rafael Correa of Ecuador, and Hugo Chávez of Venezuela at the World Social Forum in 2008. Photo by Agência Brasil.

It was not long before another Latin American government fell into Washington’s crosshairs. In 2009, the government of Manuel Zelaya in Honduras was toppled by the military. According to a report by The Intercept, President Obama initially stated “the coup was not legal” and his administration pledged to “cut off contact with those who have conducted the coup.” However, the administration soon faced immense pressure to support Zelaya’s overthrow:

“A retired U.S. military intelligence officer, who helped with the lobbying and the Honduran colonels’ trip, told me on condition of anonymity that the coup supporters debated ‘how to manage the U.S.’ One group, he said, decided to ‘start using the true and trusted method and say, “Here is the bogeyman, it’s communism.” And who are their allies? The Republicans.’

A network of former Cold Warriors and Republicans in Congress loudly encouraged Honduras’s de facto regime and criticized the newly elected Obama administration’s handling of the crisis. Zelaya, so his critics alleged, was simply an acolyte of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, public enemy No. 1 of the U.S. in the hemisphere.”

The State Department, under the leadership of Hillary Clinton, resumed contact with the regime and ultimately determined that the ousting of Zelaya was “not a ‘military’ coup.” During the process of negotiating new elections, U.S. officials blocked an O.A.S. resolution calling for Zelaya’s return to the presidency as a precondition and the subsequent election was won by military-backed, right-wing candidate Porfirio Lobo.

Honduras is now governed by right-wing President Juan Orlando Hernández, who took power through elections marked by fraud and political repression in 2013 and again in 2017. The O.A.S. itself called for new elections, but they never came. Despite this, the United States immediately recognized Hernández’s government. Even though much of the aid supplied to Honduras by the United States is supposed to depend on the government’s compliance with human rights, Hernández’s government has continued to receive tens of millions of dollars in support even as U.S.-trained army units have been implicated in the murders of dozens of anti-coup activists and social leaders, including world-renowned Indigenous leader and environmental activist Berta Cáceres. According to the United Nations Human Rights Council, “impunity is pervasive, including for human rights violations, as shown by the modest progress made in the prosecution and trial of members of the security forces for the human rights violations committed in the context of the 2017 elections.” President Hernandez’s brother Tony was, “found guilty on counts of ‘Cocaine Importation Conspiracy’ and ‘Possession of Machine Guns and Destructive Devices’,” and his sister Hilda was, “the subject of a major drug trafficking and money laundering investigation by U.S. authorities.” Fabio Lobo, son of former President Porfirio Lobo, “received a twenty-four-year sentence in U.S. prison following a guilty plea of ‘conspiring to import cocaine into the United States.’” The coup in Honduras, supported by the United States as a result of the same “anti-Communist” drive which led it to support vicious tyrants in the 20th century, transformed a democratic nation with a center-left government into an authoritarian, right-wing narco-state.

This does not appear to be a problem in Secretary Pompeo’s eyes:

“As I said in Santiago last year, in 2019, people of the Americas have brought a new wave of freedom, freedom-minded governments all throughout our hemisphere. Only—only in Cuba and Nicaragua and Venezuela do we face stains of tyranny on a great canvas of freedom in our hemisphere.”

Secretary Pompeo appears to be referring to the recession of the Pink Tide in recent years through the election of right-wing governments in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay. This has been compounded by Venezuela’s economic and political crisis and the coup against Evo Morales’ government in Bolivia. He employs the same Cold War-era strategy of describing left-wing governments, even if they are democratically elected, as “tyrannical” while right-wing governments, which are often themselves deeply authoritarian and guilty of human rights violations, are described as “freedom-minded.”

One of the most well-known representatives of this “wave of freedom” is Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, winner of the 2018 election after former President Lula da Silva, who left office in 2010 with record-high approval ratings, was barred from running. Bolsonaro has called Brazil’s aforementioned military dictatorship “glorious” and stated that, “the error of the dictatorship was that it tortured but did not kill.” He has also praised the genocide of Indigenous people, telling the Brazilian Congress in 1998, “the Brazilian cavalry was very incompetent. Competent, yes, was the American cavalry that decimated its Indians in the past and nowadays does not have this problem in their country.” Bolsonaro was also recently linked to the individuals accused of murdering Afro-Brazilian activist and politician Marielle Franco.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (left) at Jair Bolsonaro’s (second from left) inauguration ceremony in 2018. Photo by U.S. Embassy Brasilia.

Another friend of Pompeo’s is Chilean President Sebastian Piñera. As protests spread throughout the country in response to austerity measures and social inequality, Piñera’s government forces have been found responsible for “133 acts of torture and mistreatment, 24 cases of sexual violence and isolated cases of psychological torture, including simulated executions, threats of forced disappearance and threats of rape” as well as “thousands of detentions and injuries” as they violently repress demonstrations.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (third from right) meets with Chilean President Sebastian Piñera (fourth from left) in Santiago, Chile, 2019. Photo by Ron Przysucha.

Chilean protestors gather in Plaza Baquedano, Santiago, Chile, 25 October 2019. Photo by Hugo Morales.

Secretary Pompeo likely knows all of this. The problem is that to him, just like to so many of his predecessors, hypocrisy is simply part of the game. The underlying goal is decidedly not to secure the self-determination and well-being of the peoples of the Americas; rather, it is to preserve the ongoing domination of the hemisphere by the United States.

For this reason, Pompeo thanks the O.A.S. for its role in “helping the Venezuelan people, they who are so downtrodden and starving because of Maduro’s cruelty,” and “bolster[ing] Juan Guaidó’s legitimacy in the international community, despite Maduro’s best efforts to undermine him.” The reality is that, due to United States sanctions on Venezuela, there are “more than 300,000 people who are estimated to be at risk because of lack of access to medicines or treatment because of sanctions on the country. That includes 16,000 people who need dialysis, 16,000 cancer patients and roughly 80,000 people with HIV, according to a report published in April by the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research.” Guaidó, who proclaimed himself “Interim President” of Venezuela, has been linked to far-right Colombian paramilitary groups and his staffers have been accused of embezzling millions of dollars in humanitarian aid funds. Guaidó’s representative in the U.S., Carlos Vecchio, has been accused of committing $70 million worth of fraud in CITGO, the Venezuelan state-owned oil subsidiary which had its assets frozen by the United States government.

Similarly, Pompeo praises the O.A.S. for its role in facilitating the coup against Evo Morales in Bolivia:

“More recently, the O.A.S. honored the former Bolivian government’s request to conduct an audit of the disputed election results. The probe conducted uncovered proof of massive and systemic fraud. It helped end the violence that had broken out over the election dispute. It helped the Bolivian Congress unanimously establish a date and conditions for a new election. And it honored—importantly, it honored the Bolivian people’s courageous demand for a free and fair election, and for democracy.”

The O.A.S.’s claims of “massive and systemic fraud” were undermined by a statistical analysis conducted by John Curiel and Jack R. Williams, two scientists from M.I.T.’s Election Data and Science Lab, which concluded that, “The statistical evidence does not support the claim of fraud.” However, the claims made by the O.A.S. following the election facilitated the ousting of Morales and his allies by the military, allowing the de facto government of Jeanine Áñez to take power as Morales went into exile. Widespread demonstrations in support of Morales, who was the first Indigenous president in the country’s history and oversaw the nationalization of the hydrocarbon industry to fund investment in social programs, were met with violent repression by the new regime. The regime itself has been marked by open anti-Indigenous racism. According to an open letter released by dozens of public figures including Noam Chomsky, Angela Davis, and others,

“Shortly after Áñez was declared President, she thrust a massive Bible into the air and proclaimed ‘The Bible has returned to the palace!’ Three days earlier on the day of Morales’ ouster, Luis Fernando Camacho, a far-right Santa Cruz businessman and ally of Áñez, went to the presidential palace and knelt before a Bible placed on top of the Bolivian flag. A pastor accompanying him announced to the press, ‘The Pachamama will never return to the palace.’ Opposition activists burned the wiphala flag (an important symbol of Indigenous identity) on various occasions.”

They also discussed ongoing human rights violations:

“Thousands of largely unarmed protesters, mostly coca-leaf growers, gathered peacefully in Sacaba, a town in the department of Cochabamba, on the morning of November 15. After unsuccessful negotiations to march to the town square, protesters tried to cross a bridge into the city of Cochabamba, heavily guarded by police and military troops. Soldiers and police fired tear gas canisters and live bullets into the crowd. During the two-hour confrontation, nine protesters were shot dead, and at least 122 were wounded. Most of the dead and injured in Sacaba suffered bullet wounds. Guadalberto Lara, the director of the town’s Mexico Hospital, told the Associated Press it is the worst violence he has seen in his 30-year career. Families of the victims held a candlelight vigil late Friday in Sacaba. A tearful woman put her hand on a casket and asked, ‘Is this what you call democracy? Killing us as if we counted for nothing?’”

Once more, in the name of upholding democracy, the will of the public was subverted and the will of the United States was imposed. Innocent people would again pay with their lives and the social advances made by marginalized groups would once more be rolled back.

Despite harsh opposition from subsequent presidential administrations in the United States and the subservience of the O.A.S. to these administrations, Pink Tide governments were able to make large strides in reducing poverty, economic inequality, and illiteracy while expanding access to education and healthcare: “as Gini scores bear out, Pink Tide countries became the most equal countries in the region, with Venezuela and Argentina leading the way. Even Bolivia, which in 2000 shared with Brazil the distinction of being the region’s least equal country, pushed its coefficient from .6 to .47 during Morales’s first five years in office, a drop few societies have ever experienced.” According to the World Bank, more than 70 million Latin Americans escaped poverty between 2003 and 2011. Now that many Pink Tide governments have been ousted and the longest-serving and most radical government of the group, Venezuela’s, is facing an ongoing economic crisis that has devastated the standard of living of its people, it remains unclear how many of these advances will survive the coming years.

Supporters of Evo Morales rally in Cochabamba, Bolivia, 4 July 2013. Photo by Cancillería del Ecuador.

However, the Pink Tide is not over. In Mexico’s 2018 presidential election, left-wing candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador broke decades of right-wing rule while calling for the “Fourth Transformation” in the country’s history, referring to previous revolutionary periods. In Colombia, a staunch U.S. ally whose politics have been dominated by the anti-Communist right for decades, progressive Senator and former mayor of Bogotá Gustavo Petro was able to secure a place in the 2018 presidential runoff election, the first time a left-winger had done so in generations. The winner of the runoff, right-wing candidate Iván Duque, has faced mass protests against his government’s austerity measures as well as the continued violence committed by far-right paramilitaries against social leaders. Right-wing governments in Ecuador and Haiti have faced similar mobilizations. In Argentina, left Peronist candidate Alberto Fernández recently won the presidency with former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as his running mate, defeating right-wing incumbent Mauricio Macri. The resurgence of the left, including in countries which were not originally considered part of the Pink Tide, demonstrates that this process is very much ongoing; the Latin American left should not be counted out just yet.

Pro-Morales mural in Villazón, Bolivia, 2012. Photo by Randal Sheppard.

Text, from top to bottom: “Bolivia in Action. To live better. Bread-Shelter-Work. Evo-lution.”

Anti-imperialist mural in Caracas, Venezuela, 4 October 2011. Photo by Erik Cleves Kristensen. Text: “Imperialism Out. Only the people can save the people.”

Looking Backward and Moving Forward

This is the ongoing legacy of the United States in Latin America. In the name of democracy and freedom, innocent people are murdered and imprisoned. In the name of self-determination and integration, communities are subjugated and fractured. Then, when the victims of these crimes flee from their homes and arrive at our borders or on our shores, our government does not hesitate to smear them as “illegals.” When the people of Latin America elect governments which recognize and denounce the bloody past and present of American foreign policy, our media will denounce them for succumbing to “populism” and “anti-Americanism.” Perhaps now one can see why Simón Bolívar, known throughout the continent as “El Libertador”—The Liberator—once lamented, “the United States appear to be destined by Providence to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.” His prescient words, spoken in 1829, carried more truth than he knew.

But, as Secretary Pompeo reminds us as he concludes his speech, “it’s up to each of you, it’s up to each of us to protect dignity and rights. It’s up to us to conduct diplomacy as brothers—and sisters—of the citizens that we each represent. It’s up to us—it’s up to us to sustain a multilateralism that truly works.”

If we are to believe him, if we are to believe that each of us does have the responsibility to stand up in the name of dignity and rights, to foster friendship and diplomacy across the continent and the world, perhaps we can take a moment to look in the mirror and understand how the United States has impeded these same goals over the past two-and-a-half centuries. Until then, and until the United States is able to accept a truly independent Latin America, it is likely that the O.A.S. will remain, as Fidel Castro dubbed it in 1962, the Yankee Ministry of Colonies.

Christian Pichardo is a staff writer at CPR and a sophomore in Columbia College studying Political Science and Latin American and Caribbean Studies. He was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic and grew up in South Florida.