Short-term Shock or "New Normal": Oil's Impact on Saudi Policy

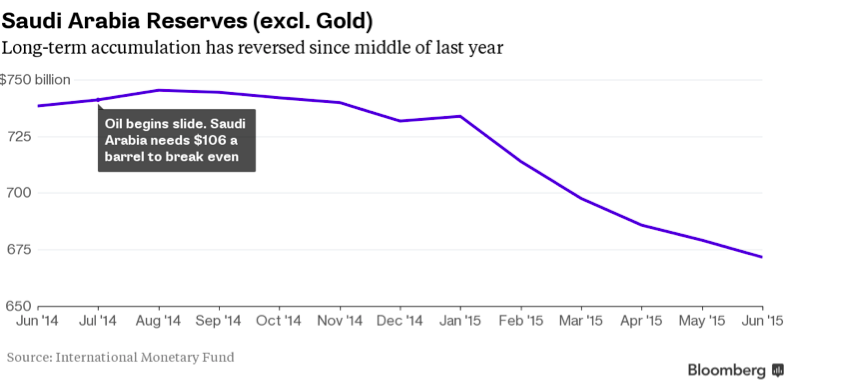

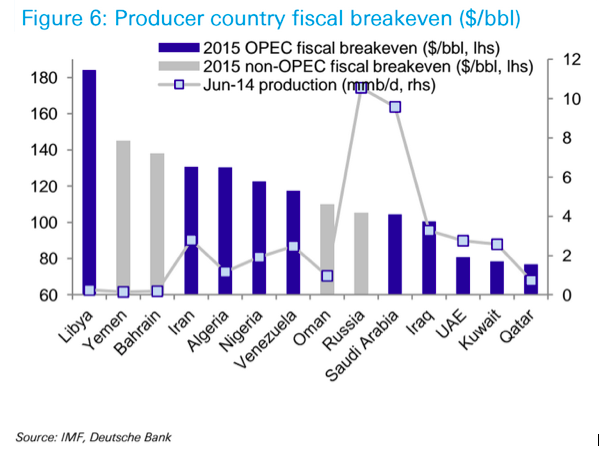

With oil hovering around $30 a barrel, investors are parsing the balance sheets of oil companies, separating the feeble from potential survivors. While (some) companies may be the first to reach insolvency, should prices remain suppressed the stability of entire nations may come into question as well: Russia relies on oil for 50% of government revenue, Venezuela 40%, and Nigeria 75%. The Gulf states are even more reliant -- Saudi Arabia’s figure stands at 90%. While many of these governments are unstable in the best of times, this environment may cause some to topple. Russia’s economy contracted nearly 4% last year and the government is rapidly spending its rainy-day fund. Venezuela is nearing a state of hyperinflation and sports a triple C credit rating. Nigeria’s economy is slowing and its budget deficit for the next year is projected to double. Oil prices are also beginning to rock Saudi Arabia, threatening a long-held reputation for stability and control. The government’s budget balances with oil at $100 a barrel. Accordingly, the government is now running $90 billion annual deficits, with hampered oil revenues worsened by increasing military expenditures. While the Kingdom prepared for this eventuality with massive central bank reserves, those have fallen from $732 to $623 billion over the past year, and without a rise in prices they will fall by at least another $90 billion over the next year. The projected 2016 deficit of $107 billion would give the nation less than six years of solvency with current reserve levels, and the IMF has predicted only five. Before that point is reached, there would be assaults on the riyal’s peg to the dollar and considerable cuts to many of the services on which citizens have come to rely. Economic troubles could even conceivably provide an Arab Spring-style spark that threatens the Saud family’s firm grip on power.

Like other OPEC nations and oil companies, the government is trying to prepare for continued difficulties. Prized oil and water subsidies have been reduced, the budget cut by almost 15% and the economy opened to new foreign businesses. The kingdom is even considering its first real system of internal taxation. A hinted Saudi Aramco IPO has been perhaps the most surprising step considered so far. While publicly offering a company that provides 90% of the government’s revenue would be drastic, the logic makes sense: even at a relatively conservative $3 trillion valuation, offering 5% of the company would raise $150 billion, more than enough to cover this year’s deficit.

Still, these steps only temporarily extend the time the Saudi government can remain solvent. This reflects the government’s overall strategy -- shore up financially and wait for prices to rise. Many had assumed the latter would involve cutting production in conjunction with OPEC. While nine members of the organization seem to be strongly advocating this course of action, the four Gulf nations, led by Saudi Arabia, vehemently oppose. Not only are these four nations larger producers, OPEC also only works by unanimous vote. Instead, Saudi Arabia actually increased production last year by 300,000 barrels a day, second only to Iraq. The nation’s decision makers have clearly decided that cutting production will not have the desired effect. Instead, they have taken the opposite route, raising production to protect market share and help drive high-cost producers out of the market. The recent Saudi-led call for a new production freeze was only an extension of this strategy. With Saudi production already at an all-time high, the move is meant to slow down the world’s fastest growing oil producers -- Iraq and Iran -- both of which directly threaten Saudi market share. Unsurprisingly, both of these nations have balked at the plan.

While North American producers are struggling, there are flaws in this strategy. Even if prices rise once enough North American drillers are forced out, these nimble firms can quickly return to the market as soon as it becomes profitable again. The profitability benchmark may also not be as high as once believed. At a recent SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy event, Adam Sieminski, an administrator at the U.S. Energy Information Administration, suggested that most shale producers can survive on prices between $25-50 a barrel and can thrive with new exploration over that level. Furthermore, although Saudi Aramco’s chairman has optimistically predicted that “moderate” oil prices will be supported by growing demand, it is fear of demand stagnation, particularly from China, that is helping to drag prices down.

The question is ultimately whether the world is experiencing a short-term market disruption or an entirely new equilibrium over lower prices. This distinction will, of course, have huge effects on future Saudi policy. In the former case, the kingdom’s waiting game should work. This could be considered a two hikers and a bear scenario: when two hikers in the forest spot a bear charging towards them, one bends down to tie his shoe. The other protests, “you can’t outrun a bear!” As the shoe-tier takes off running, he turns around and explains that he doesn’t have to outrun the bear. “I just have to outrun you.” In this scenario Saudi Arabia simply needs to cut its budget, build up cash reserves (with moves like a Saudi Aramco IPO), and “outrun” the other oil producers.

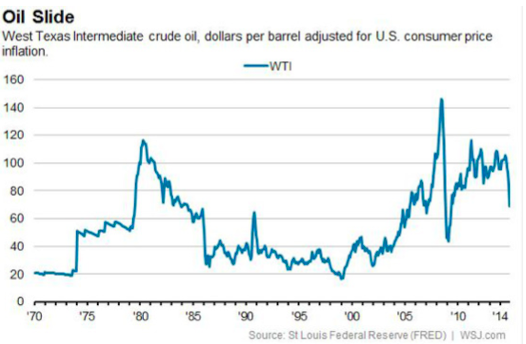

In a new equilibrium situation, Saudi Arabia, along with all oil-reliant nations, is in a far more precarious position. Recall the fiscal breakeven prices of oil for these nations. Saudi Arabia’s sits over $100 a barrel. Any situation in which oil prices remain far below this price will require more than just budget cuts. The system all the Gulf nations have enjoyed -- heavy government spending supported by massive oil revenue and a limited number of beneficiaries -- will be fundamentally threatened. While falsely imagining a “new normal” in the midst of an ongoing crash can be easy (for example, believing that tech companies deserved their astronomical valuations in 2001), history validates this possibility. Between 1975 and 1985, oil prices spiked considerably, spending five years above $80 a barrel (inflation-adjusted). A twenty-year period then ensued during which oil rarely passed above $40 a barrel. While oil prices have now been above $80 a barrel for ten years (excluding during the financial crisis), there is no reason to believe oil cannot return to a much lower equilibrium price driven by technological advancement, sluggish global demand growth, and an increasing number of price-insensitive suppliers (most notably, Iran and Iraq). Perhaps the “new normal” was to believe that oil would remain at a permanently higher price.

The Saudi government has announced that a plan will soon be released in conjunction with McKinsey to develop a domestic economy and decrease oil dependence. Still, this type of transformative plan has been on the table for decades in all of the Gulf nations -- and never fully enacted. Even if the plan does go forward, building an economy essentially from scratch is neither a quick or simple task. Other nations may be more vulnerable, but in a new equilibrium situation, even the Saudis are threatened.