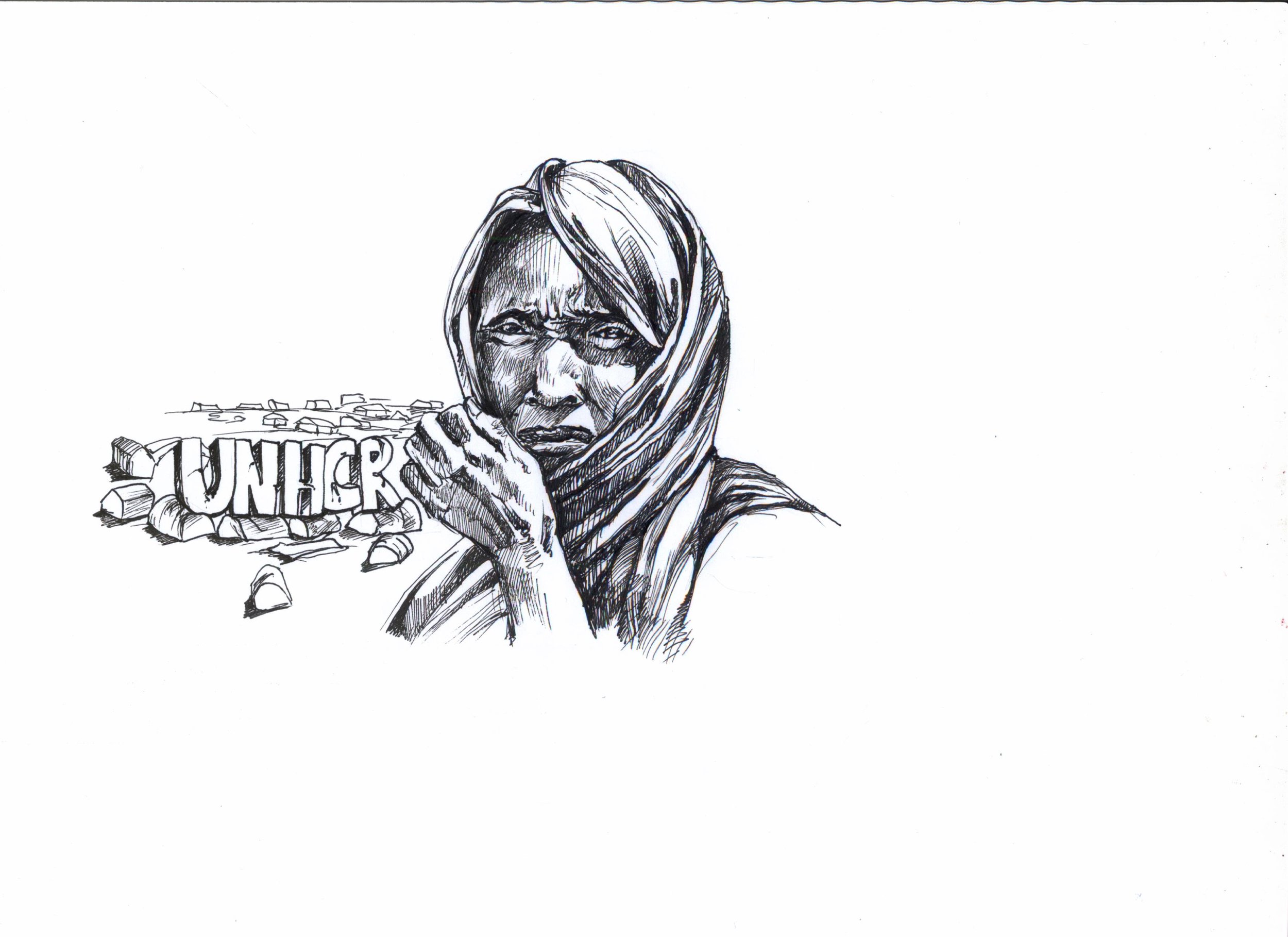

UNderserved Refugees: Systemic Failures of the UNHCR in Kenya

In some respects, the current Somali refugee crisis began when the sitting president and despot, Siad Barre, was toppled from power by a combined force of opposition rebel groups in 1991. Different factions of al-Shabaab militant groups started fighting each other for power, and the antagonism between Islamists of al-Shabaab and Somalia’s transitional government, backed by African Union peacekeepers, exacerbated the conflict. The first phase of the civil war took place between 1986 and 1992 when Barre was overthrown, and stemmed from the insurrections against his repressive regime. After his ousting, a counter-revolution took place to attempt to reinstate him as leader of the country. The country, especially the south, descended into anarchy. As the war continued, Somalia was devastated by a two-year drought, which caused reduced harvests, food inflation and a steep drop in labor demand and household incomes.The combination of mass starvation, terror from various warlords, and the prolonged drought forced people from their homes and fields, which exacerbated food shortages. Under these conditions, clan-based warlords competed with each other with no one controlling the nation as a whole. The result was a mass exodus of refugees to neighboring Kenya. The refugees mostly settled in one of Nairobi’s estates, Eastleigh, and due to the high rents some Somalis could afford to pay for houses, local Kenyans were soon driven out. Landlords discovered that the refugees were not averse to paying triple the rent each month, and this earned Eastleigh the name “small Somalia.” However, even though the Somali citizens had Kenyan identity cards, they were not considered “authentic” citizens by the host country. When the Somali refugees fled their country and came to Kenya, they lost their Somali citizenship rights, and even though they gained refuge in their host country, they lost certain human rights within Kenya.

Prior to the war, Kenya became a leading host of refugees from other East African nations. The roughly 12,000 refugees in Kenya at that time enjoyed the legal right to reside anywhere in the country, obtain a work permit and attain an education. It was not until the early 1990s, when nearly every country surrounding Kenya experienced political crises due to the instability in Somalia, that Kenya transitioned from a host to a hub for refugees, and refugees flooded the country in droves. By early 1993, there were 500,000 Somali refugees in Kenya. The government of Kenya became overwhelmed by the situation and, under pressure from xenophobic domestic citizens, decided to eventually withdraw from providing humanitarian assistance to refugees, citing that the refugees were an economic and environmental burden and a terrorist threat due to their links to al-Qaeda affiliates in Somalia.

From a legal perspective, the Kenyan government has been required to accept refugees because it is a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and ratified the 1969 OAU Convention pertaining to refugees. Although the government has legally abided by the above statutes, it has also created numerous informal and unwritten policies like the encampment policy, which is also standard UN High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) policy, and which affords no rights to refugees because it requires them to stay within camps at all times. Somali refugees and Kenyan-born Somalis have complained that both the government and the UNHCR constantly discriminate against them. The most fundamental of rights—their right to life—remains largely unassured. We therefore have to ask, how and why do we see human rights violations in the Kenyan camps that are under the humanitarian administration of the UNHCR?

The protection of the rights of a nation’s refugees depends largely on the willingness of the state to respect and protect the rights of its residents and, in the event of a state’s desertion of its duties, the will of outside powers to step in as a fallback. But the UNHCR has become a co-conspirator in perpetuating Somali refugee rights violations in Kenya. Any act of intervention, such as the humanitarian aid that is provided by the UNHCR, is also an act of control and governance, and with this control comes power. The simultaneous presence of care and control has created a state within a state.

The UNHCR thus violates refugee rights in two ways: first, through problems of accountability, as there is no check over the power that the UNHCR exercises over refugees; and second, through the temporary status of refugees. The UNHCR defines accountability as a commitment to deliver results to populations of concern within a framework of transparency, agreed feasibility, delegated authority, and available resources. From the beginning, the definition is problematic because the UNHCR gets to define its own version of transparency. Secondly, the definition of “feasibility” has a convenience tag attached to it. The fact that accountability is also related to availability of resources is problematic because doing so makes refugee rights flexible and subject to the convenience of the availability of resources. It is generally accepted that accountability is essential because it ensures more effective protection of rights by providing individuals with the opportunity to seek redress. Even though the UNHCR is largely checked by donors on whom they rely for funding, this method of checks and balances is insufficient because it takes a top-down approach and focuses on bureaucracy as opposed to looking from the bottom up, where the violations at the individual level that have the most impact on refugee rights actually occur.

The UNHCR also exercises great power over the lives of refugees. Accompanying this power is a lack of checks and balances from peer agencies. Humanitarian agencies do not “check” each other because they are allies in the humanitarian field. Checking an ally would draw attention to oneself and create powerful enemies, so the UNHCR is largely left alone by other UN agencies that have the potential to check its power. In this regard, it is accountable only in so far as it submits reports to donors; these reports are self-generated and biased in the UNHCR’s favor.

Further compounding the issue of accountability is that the authors of various reports and recommendations regarding the UNHCR are often the senior protection staff, the head of the sub office or the senior protection officer at the camp. These senior personnel are often submitting reports to their superiors, whom they depend on for promotions and reassignments. Self-promotion and self-preservation thus prevent them from candidly talking about their failures. This image management spills over to include misrepresentation of facts by glossing over failures and emphasizing achievements. For example, while I was a refugee in Uganda in 2010, we did not receive food rations for 10 days because the plane that brought in the rations had not yet arrived. However, journalists who came to visit the camp were accorded a lavish visit and dined like kings on food that was not made available to us. When budget cuts forced cutbacks, UNHCR staff prioritized provisions for visiting journalists over those for refugees.

Further compounding the issue of accountability is that the authors of various reports and recommendations regarding the UNHCR are often the senior protection staff, the head of the sub office or the senior protection officer at the camp. These senior personnel are often submitting reports to their superiors, whom they depend on for promotions and reassignments. Self-promotion and self-preservation thus prevent them from candidly talking about their failures. This image management spills over to include misrepresentation of facts by glossing over failures and emphasizing achievements. For example, while I was a refugee in Uganda in 2010, we did not receive food rations for 10 days because the plane that brought in the rations had not yet arrived. However, journalists who came to visit the camp were accorded a lavish visit and dined like kings on food that was not made available to us. When budget cuts forced cutbacks, UNHCR staff prioritized provisions for visiting journalists over those for refugees.

Complicating issues further is the temporary state of refugees in Kenya. The UNHCR keeps refugees in a temporary state because it gives the UNHCR power to act as a state within a state. By issuing identity cards to refugees in camps, deciding who is eligible for refugee status and who is not, they take on a role more akin to a government than a third-party agency. By acting as a state within these territories that are not quite theirs, but which they have been given by the state government to use for their humanitarian activities, they create jurisdictional ambiguity. This further reduces accountability for the UNHCR.

Because the UNHCR issues refugee permits, it decides the duration of refugee status. This duration is contingent on a number of factors that create a temporary situation that adds to the problem. How long or short is temporary? As the UNHCR posed, “when does the short term solution cease to be acceptable?” The war in Somalia has been going on for almost twenty-four years, and camps are no longer temporary solutions, but permanent settlements. Though the UNHCR began its efforts to protect refugees, it slipped into a state-building role. The very principles that had been designed to save lives now looked like excuses for inaction. No longer satisfied with keeping refugees alive, the UNHCR delved into post-conflict reconstruction, human rights, development, democracy promotion and peacebuilding. Finally, it found itself taking on the role of the state government. This displaced it from its original role. Unfortunately, its mutated form has been unable to cope with its original mandate and this is why we see so many violations, since the UNHCR was not created to act like a government in its taking care of refugees. Its evolution from temporary protector to established provider has forced it to take on new roles for which it is ill-equipped.

The UNHCR, as part of the its mandate, has the power to forcibly return displaced people to their previous lives. This idea disregards the fact that some refugees, who were previously nomads and farmers have now become urbanized and given birth to children in urban dwellings, do not have the skills to survive living in arid and dry lands because they have not adapted to such situations. By exercising these powers, there is completely unchecked impunity, but even more worrying is how privatization has entered the realm of humanitarianism through subcontracting of supplies required for day-to-day subsistence. Though the UNHCR is staffed by salaried professionals, they contract and subcontract tenders to service and goods providers and have effectively become part of networks that dominate and control refugee lives by selecting who gets rations and who does not.

Since its formation in 1950, the mandate of the UNHCR has expanded. Because human rights are constantly evolving, the UNHCR has had to cope with these changes. It has been called upon to deal with emerging crises when signatory states have failed to live up to their obligations to uphold human rights. However, it has found itself in a very complex situation as the expansion of human rights begins to threaten state sovereignty. The UNHCR itself says that the organization “has been transformed from a refugee organization into a more broadly based humanitarian agency”. Even though its focus has expanded to cope with the exigencies of refugees, the concept of territorial sovereignty and a country’s integrity has not changed. Because international law does not clearly define the limits of territorial sovereignty, Kenya has used terrorist threats as a safe house that it retreats to anytime security is threatened, and the UNHCR is then powerless to act against Kenya’s territorial integrity. For example, when Kenyan-Somali terrorists carried out grenade attacks and butchered 147 high school children in the North Eastern province on April 2, 2015, the Kenyan government responded by giving the UNHCR a 3-month ultimatum to relocate the Dadaab refugee camp from Kenya to Somalia. In a speech that was aired on national and international media and with widespread support from Kenyans at home and abroad, Deputy President William Ruto said, “We have asked the UNHCR to relocate the refugees in three months failure to which we shall relocate them ourselves,” adding that “the way America changed after 9/11 is the way Kenya will change after Garissa.” Thus, under the guise of security dilemma and zero sum games, states give attention to notions of collective security at the expense of human rights, and the UNHCR is forced to play a compromised and secondary role in the advocacy of the very mandate for which it was created.

However, the UNHCR is not as toothless as it seems. Even as it presents an impression of humanitarianism, the UNHCR in Kenya forces the refugee to beg for refugee status. Refugees have to prove why they should be granted this status. In order to prove extenuating circumstances, they must bear the physical scars; only then are their stories believable and are they considered for identification cards. Even after they have been accepted into the camps, life there is grim. Refugees complain about the lack of education for their children and insufficient food. Guglielmo Verdirame, in his book Rights in Exile: Janus-Faced Humanitarianism, speaks of an account in April 1994, when a number of unidentified refugees started a protest to speak out against the injustices in the camp and in the process, destroyed enclosures. In order to punish them, food distribution was withheld from the camp for 21 days. When journalists and researchers went to investigate these incidents, the refugee camp leader abruptly told them that he was under instructions from the UNHCR not to allow any “outsiders” inside the camp unless the UNHCR had authorized them. This was despite the fact that they had documents and clearance from the Kenyan government to visit the camps. The UNHCR views the camps as their “space” where they are allowed to exercise territorial sovereignty and where they decide who gets in and who stays out.

Kenyan legislation is shaped by its territorial sovereignty and concerns about national security. However, one has to ask why the UNHCR does not challenge this legislation. It is against this backdrop that I make the claim that Kenya’s reaction to the Somali refugees is supported silently by the UNHCR, first because the UNHCR relies on the willingness of the Kenyan government to let it stay in the country and carry out its operations, and second because the UNHCR has assumed governmental powers itself by administering refugee camps and conducting refugee status determination. By taking on these roles, the UNHCR has repositioned itself in relation to the states, which have now become an ally and an accessory to its violations.

By states and the UNHCR pretending to be consensual, refugees are viewed as a form of excess by both groups. The Kenyan government sees them as a security threat that needs to be offloaded into Somalia, and the UNHCR sees them as undesirables that they have to deal with. In the interplay between states, the UNHCR, and refugees, the UNHCR are the idealists who advocate for humane conditions for mass refugees by citing tolerance and pluralism, states are the realists who prioritize collective security above human rights by citing protectionism and fear, and the refugees are the voiceless and stateless peoples caught in between.