Film Review: Foreigners Out! Schlingensief’s Container

"Amnesty International would have done it differently,” German artist Christoph Schlingensief says of his political art project in the 2002 documentary Foreigners Out! Schlingensief’s Container, alternately named Please Love Austria. He is right on the mark. Inspired by the reality series Big Brother, Schlingensief’s project is gruesome: take twelve asylum seekers from across Austria, place them in a makeshift container home in central Vienna, and film them for six days. Then invite the country to vote online to deport two of the migrants each day, until only one remains. Throughout the project, Schlingensief fancies himself neither fully an artist nor fully a politician. He is, rather, a self-proclaimed truth-teller. In 2000, when he launched the project, Austria’s center-right party had just announced a coalition with the Freedom Party (FPÖ), a xenophobic group formed from Nazi remnants. Schlingensief’s project is a criticism of the coalition, and while the film leans liberal, that is not the focus of the work. Schlingensief places honesty above politics: he is less bothered by the xenophobia in Austria than by the denial—on both the right and the left—that such xenophobia has come to define the nation.

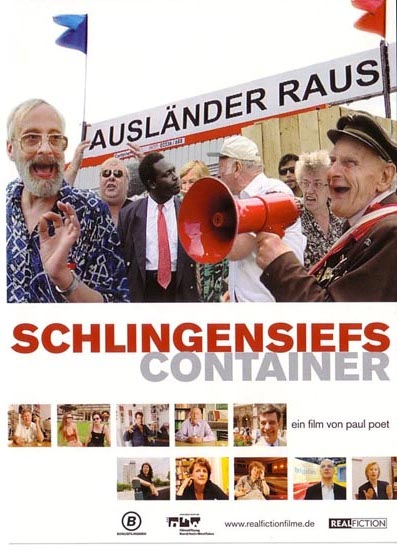

The beginning of the film, a crowd gathers around the container homes, and we learn Schlingensief’s designs: “Please take many pictures of this place. Take them home with you, show all your relatives and friends what is going on in Austria,” Schlingensief says. The camera cuts to his assistant, but he does not pause. “Show them the future of Europe! Tell them: This is the truth! This is Austria!” The assistant tears off a panel of construction paper, unveiling a massive plastic banner. “AUSLÄNDER RAUS”, it reads. “Foreigners out.”

The sign looms above the city center and the migrants. It is the third and final element of the project: There are the xenophobes and their Ausländer Raus sign; the migrants and their liberal supporters; and Schlingensief himself, a sort of interlocutor and provocateur. As tourists and residents alike pass by the project, Schlingensief speaks with them. He hands them his megaphone, he asks them questions. Sometimes he just affirms their beliefs. Both the project and Schlingensief become objects of ire: “You are an enemy to Austria and you need to be deported,” one liberal elderly man tells Schlingensief.

The sign looms above the city center and the migrants. It is the third and final element of the project: There are the xenophobes and their Ausländer Raus sign; the migrants and their liberal supporters; and Schlingensief himself, a sort of interlocutor and provocateur. As tourists and residents alike pass by the project, Schlingensief speaks with them. He hands them his megaphone, he asks them questions. Sometimes he just affirms their beliefs. Both the project and Schlingensief become objects of ire: “You are an enemy to Austria and you need to be deported,” one liberal elderly man tells Schlingensief.

But Schlingensief loses neither composure nor focus. The declaration that he should be deported ties into his thesis that the problem in Austria is that no one can agree on what Austria is. For the liberals, it is a free and tolerant democracy; for the xenophobes, it is a proud nation, under threat from foreign influence, be that influence a German artist or a Middle Eastern asylum seeker. In any case, migration proves a critical test for Austria, as the decision of whether to admit a migrant must depend not only on who the migrant is but also on what the state is.

In defining their country, Austrians look to their history—not as a means of learning from the past, but as a means of defending their conception of the nation. “At that point, [the Freedom Party] pledged that Austria is no immigrant country, despite the fact that this completely contradicts the country’s history,” Burghart Schmidt, a cultural philosopher, notes in the film. “So this broke with the Austrian tradition through the very same politicians who were talking about historical commitment.”

Schlingensief, for his part, plants the Ausländer Raus sign by the opera, Vienna’s most famous attraction. “Here you can see what country Austria really is! We are a country of culture,” one onlooker shouts. “Listen to Mozart! Go to the opera!” But so too, Schlingensief suggests, is Austria a country of intolerance. Before his project, few would shout it so loudly, so publicly.

Though Schlingensief appears more interested in provocation than politics, he has one clear target in the film: the media. “It doesn’t fucking matter if it’s the [Social Democratic Party] or [Freedom Party] or [People’s Party]. The Krone is the Krone and thus the main party of the country,” he says, referring to Austria’s major daily, which reaches 43 percent of the public, with one million copies distributed daily in a nation of 7.4 million. It is, according to the film, the largest print monopoly of any paper worldwide.

“Whoever buys that paper in the morning, votes for that party,” Schlingensief argues. “And there is nothing to stop that process. Who we believe to be the ruling party usually is not. Yellow press is the only real political party out there.” The asylum seekers, in a brilliant irony, planned or unplanned, are ushered in and out of the container homes with newspapers and magazines covering their faces, protecting their identities—and hiding them.

Never in the film does Schlingensief comment on these moments of irony. Never does he mention the word satire. He does explicate his method: “You don’t need to comment to articulate criticism. It is enough to simply quote what you criticize. The quotes just need to be placed in the right time and place. Then suddenly a simple citation becomes self-revelatory.”

Shockingly few Austrians take his project as art; too many of them identify with its message for it to be simply satire. “I thought this [project] would be too obvious, too intended,” Carl Hegemann, chief dramaturg at the Berliner Volksbühne, recalls in the film. “Everyone would feel preached to, ‘cause everybody would know what this whole thing really is about. And then those would just say, What the heck! We love foreigners! And it all would have puffed into hot air.... But all of a sudden the whole Austrian population seriously took part in that play.”

Austrians may have bought into the project, but that is not to say it succeeded. At one point, Schlingensief appears on TV with the FPÖ spokeswoman. The session devolves into a shouting match, a scene all too familiar in the film. Schlingensief’s work is cathartic, but it is also incendiary. “The one truly surrealist act possible is to randomly shoot into a crowd. If this is a form of radicalism, it has worked in the end,” he tells us. “You could not hear the shot, but an incredible lot of people were stumbling around and heavily wounded.”

But who, exactly, did he wound? Maybe the xenophobes, maybe the whole nation. But certainly the migrants, who are evacuated out of danger, forced to seek refuge from the same country where they once sought refuge.