US-China Power Play, and the Fiscal Play

China is slowly on the move to restore its political and economic success of yore. As an homage to the inland trade route traversing Central Asia that made China a major player in Eurasia from the 7th-10th centuries AD, President Xi Jinping has launched the “Silk Road strategy,” a series of agreements on trade and infrastructure development meant to engender free trade in the region. On November 8 of last year, the president announced that China would set aside the equivalent of $40 billion to fund the policy. This umbrella strategy primarily promotes infrastructural development through large-scale construction of ports, railways, and airports throughout both Central and South Asia. But it will also allow for investment, sale, and transport of energy goods, and the internationalization of the Chinese renminbi as a currency. There are no set standards structuring this strategy, other than “a vague idea of mutual interest and mutual respect” among China and its partner countries, according to Foreign Policy’s Min Ye. But by promoting intergovernmental collaboration of the highest level, China seeks to redouble the influence of governments and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which China has in scores.

The Silk Road strategy follows the trajectory of the increasing economic role China has sought to assume in recent years. Last November, China hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in Beijing. There, it has again pushed for the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP), which parallels United States’ Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a nexus of free trade agreements involving twelve countries. TPP seeks to cover sectors untouched by the World Trade Organization (WTO), such as service trade, agriculture, and the safeguarding of intellectual property rights, but also secures US influence in Asia. Excluded from TPP, China has created its own version of the program.

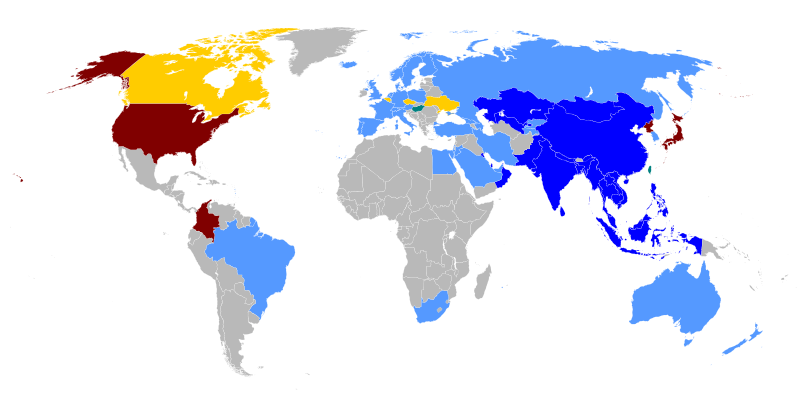

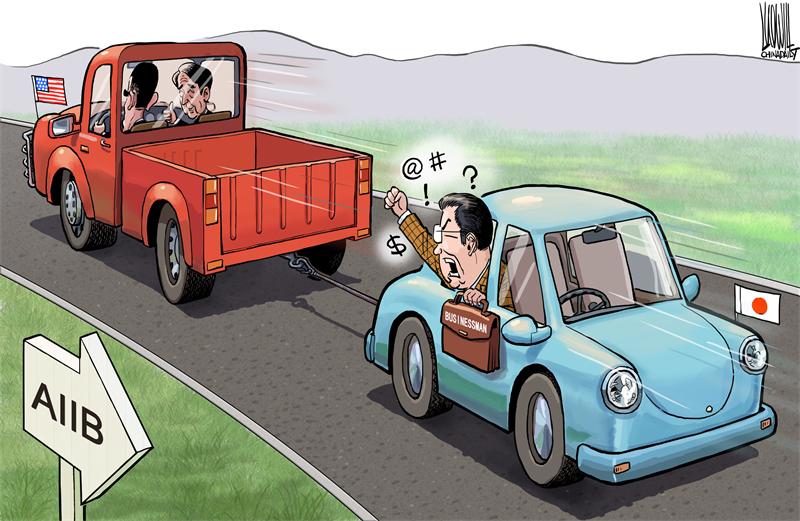

The much-discussed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), launched on October 24, 2014, is the latest item on China’s Silk Road agenda that reflects the country’s increasing willingness to establish financial instruments for itself and by itself. Headquartered in Beijing and with a starting capital base of $50 billion, AIIB is the Asia-Pacific sequel to the New Development Bank, also proposed by China and launched just last July to foster collaboration in multilateral economic development between Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). Incensed and leery of growing Chinese fiscal proactivity, the US has not only declined to join but also asked its allies to refrain from doing so. To its dismay, however, AIIB has successfully attracted American allies into its fold, now tolling more than 50 members, according to Reuters. New Zealand, Singapore, and Thailand, among others, have joined in on China’s venture. The article “The infrastructure gap” from The Economist puts their mindset in these words: “China was going to launch the AIIB anyway; better to be on the inside influencing its governance.” Countries like South Korea have reneged on their initial promise not to join, even Taiwan and Iran have teamed up with China, and Japan’s entrance is soon to come.

The much-discussed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), launched on October 24, 2014, is the latest item on China’s Silk Road agenda that reflects the country’s increasing willingness to establish financial instruments for itself and by itself. Headquartered in Beijing and with a starting capital base of $50 billion, AIIB is the Asia-Pacific sequel to the New Development Bank, also proposed by China and launched just last July to foster collaboration in multilateral economic development between Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). Incensed and leery of growing Chinese fiscal proactivity, the US has not only declined to join but also asked its allies to refrain from doing so. To its dismay, however, AIIB has successfully attracted American allies into its fold, now tolling more than 50 members, according to Reuters. New Zealand, Singapore, and Thailand, among others, have joined in on China’s venture. The article “The infrastructure gap” from The Economist puts their mindset in these words: “China was going to launch the AIIB anyway; better to be on the inside influencing its governance.” Countries like South Korea have reneged on their initial promise not to join, even Taiwan and Iran have teamed up with China, and Japan’s entrance is soon to come.

Are these nations really striving to marginalize the US, overthrowing it in an economic coup in favor of the new kid on the block? That seemed to be the impression the White House conveyed when it publicly expressed displeasure at the UK’s decision to be not just a member but a founding member of the AIIB. One US official spoke to the Financial Times, saying, “We are wary about a trend toward constant accommodation of China, which is not the best way to engage a rising power.” Due to this concern, the US has asked UK to “use its voice to push for adoption of high standards” within the AIIB.

Yet this story is not as simple as a fight over hegemony, a story perhaps too familiar from the Cold War era. China, at least, has a very legitimate excuse (or explanation) to vindicate its outright, defiant invitation to compete against the US. Funds for infrastructure development in the Asia-Pacific region have been far less than sufficient in past years, and China’s skyrocketing economy has impelled the nation to take the helm to sustain its own growth in a region that previously saw support from the US-steered World Bank and Japan-steered Asian Development Bank (ADB), both of which were inadequate in sustaining the region’s rapid economic growth. In fact, the ADB estimates that $8 trillion will be needed in the coming ten years to feed the region’s telecommunications, transportation, water system, and energy sector, with current investment funds lacking $700 billion every year. The World Bank and ADB have capital pools that add up to $400 billion, so even if these institutions were to pour all their stores into this infrastructural investment gap in Asia, it wouldn’t be enough. The around $13 billion that private investors pour into this gap every year is not only grossly insufficient but also used mostly for “low-risk projects.” AIIB emerges onto this stage with an authorized capital pool that can raise up to $100 billion, and flaunting an annual funding capacity of $30 billion as opposed to World Bank’s $24 billion. Considering how the US Senate has shied away from allowing larger capital contributions from rising market giants like China in recent years—such revamping would have doubled the store of International Monetary Fund (IMF), but would also have given greater voting power on the Executive Board to these donors—the AIIB appears a savior to countries seeking funds.

According to a Washington Post article by Raj M. Desai and James Vreeland of Georgetown University, IMF’s Managing Director Christine Lagarde foresaw China’s pursuit of “alternative options" in response to America’s exercise of its blocking vote in an effort to stunt increased representation for China, India, and Brazil on the board. Though done in a reserved tone, existing institutions such as ADB and World Bank have welcomed the AIIB into the banking world, adding even more legitimacy to the startup America wanted to dismiss: “With the right environment, labour, and procurement standards, the AIIB and the New Development, established by the BRICS countries, have the potential to become great new forces in the economic development of poor countries and emerging markets,” said Jim Yong Kim, president of World Bank.

According to a Washington Post article by Raj M. Desai and James Vreeland of Georgetown University, IMF’s Managing Director Christine Lagarde foresaw China’s pursuit of “alternative options" in response to America’s exercise of its blocking vote in an effort to stunt increased representation for China, India, and Brazil on the board. Though done in a reserved tone, existing institutions such as ADB and World Bank have welcomed the AIIB into the banking world, adding even more legitimacy to the startup America wanted to dismiss: “With the right environment, labour, and procurement standards, the AIIB and the New Development, established by the BRICS countries, have the potential to become great new forces in the economic development of poor countries and emerging markets,” said Jim Yong Kim, president of World Bank.

One cannot blame China for groping for greater influence through such institutions as AIIB. Even if it had intended wholeheartedly to challenge US prerogative in the Asia-Pacific sphere, China has claims to a legitimate objective—who can prevent a rising nation from establishing the means for its own growth, especially if such means stand to benefit others in the global community? One also cannot blame the US for trying to check the Chinese economic juggernaut, because that is what any country would do to pursue its own interests—and because the US has a right to be concerned about the Chinese commitment to transparency. Interim head of the AIIB, Jin Liqun, made it clear at the Singapore Forum on April 11, 2015 that selection of top management personnel will be by merit-based appointment and that corruption will be met with “zero tolerance.” But the fact that Jin was specifically addressing these issues reminds us of the checkered history of Chinese transparency. The AIIB is, arguably, the nation’s first transnational attempt to bind itself to transparency. Then there’s the question of Chinese “dominance” at the AIIB. After all, President Xi Jinping did propose it, the institution is headquartered in Beijing, and it is a good chunk of China’s Silk Road strategy. It should also be noted that the New Development Bank, AIIB’s twin in the Silk Road family, is likewise headquartered in Shanghai, though its presidency rests with India for now. These misgivings Jin attempts to dissipate as well: “Leadership is not a privilege—it’s an obligation,” he says.

So yes, the White House did well to point out to UK that it should be on the lookout to check the seeds of Chinese dominance at this new institution, should they sprout. But it is now the general consensus that the US made a mistake in staying out of the AIIB fold. If it is that concerned about rising Chinese economic hegemony, shouldn’t it have striven to be the insider, privy to any and every step China makes within the AIIB? New Zealand, Singapore, and Thailand had prescience in deciding to join, whether their true purposes lay in self-interest or in assuming the role of insider rivals (but then again, the two goals are highly intertwined with one another). Regardless, it is clear that the US would have been able to exercise far greater power within the AIIB had it chosen to join it. Its sense of dignity and importance aside, the US should have made a strategic decision—one that seems like forfeiting oneself to one’s rival but is in fact a calculated strategy meant to co-opt its rival, an insightful appropriation of soft power under the cover of good will and idealistic cooperation. In the world of politics, strategic voters often cast their ballot to less preferred candidates in order to see more preferred candidates be elected in less-than-ideal circumstances. This is precisely what the US should have done: act as a strategic voter in the unpalatable world of reality.

So yes, the White House did well to point out to UK that it should be on the lookout to check the seeds of Chinese dominance at this new institution, should they sprout. But it is now the general consensus that the US made a mistake in staying out of the AIIB fold. If it is that concerned about rising Chinese economic hegemony, shouldn’t it have striven to be the insider, privy to any and every step China makes within the AIIB? New Zealand, Singapore, and Thailand had prescience in deciding to join, whether their true purposes lay in self-interest or in assuming the role of insider rivals (but then again, the two goals are highly intertwined with one another). Regardless, it is clear that the US would have been able to exercise far greater power within the AIIB had it chosen to join it. Its sense of dignity and importance aside, the US should have made a strategic decision—one that seems like forfeiting oneself to one’s rival but is in fact a calculated strategy meant to co-opt its rival, an insightful appropriation of soft power under the cover of good will and idealistic cooperation. In the world of politics, strategic voters often cast their ballot to less preferred candidates in order to see more preferred candidates be elected in less-than-ideal circumstances. This is precisely what the US should have done: act as a strategic voter in the unpalatable world of reality.

Nevertheless, there is a more practical side to this misstep beyond the most observable issue of Uncle Sam refusing to give a nod to China’s undeniable ascendancy. Desai and Vreeland in their Washington Post article invoke the loss American private investors will suffer thanks to this “intransigence.” Infrastructural investments are special in the sense that they have higher initial fixed costs than regular investments, though they come with longer maturities. Unexpected turns in the political sphere that suddenly render the financial system unstable in the course of these long periods of maturity, then, harm infrastructural investors far more than other private investors. Financial intermediaries, including multilateral banks like the AIIB, are thus indispensible in infusing mutual trust and stability to this inherently unstable, unpredictable system through involvement in funding the infrastructure project itself, risk guarantees, and other mechanisms that are together called “additionality.” Although the AIIB is not yet equipped with such tools of additionality now that it has just been established, it is likely that these will be forthcoming. Unfortunately, American investors looking to fund infrastructure projects in China and other developing nations will be unable to benefit from the stability the AIIB’s additionality will provide, simply because the US is not a member of the bank.

In short, America’s decision to stay out of the AIIB qualifies as a miscalculated step both in political and economic terms. Even if China’s obtrusive headway into market economics had chafed the US’s self-esteem and sense of dignity as the world’s capitalist hegemon, the US should have masqueraded as the artful accomplice because we all know that countries around the world, whether they like it or not, face the challenge of same nature and respond as artfully: ugly reports on child labor and environmental pollution put aside, China is the rising star that cannot help but be respected, recognized, and responded to. And the US should be subtler about checking this power, if it decides to, for blunt attempts will backfire in the absence of the rest of the world’s cooperation. Checking China from within the AIIB will be far more effective and also far more feasible, considering how difficult it would be for the nation to hide information from its fellow members, especially given its recent pledge of transparency. And then there’s the logistical side of the issue as well. Any investment into these developing countries holds high prospects. In the context of recent economic doldrums, no opportunity can sound better: if you are developed and if your heyday has already passed, profit from the heyday of others. The AIIB stands to remove the only disconcerting aspect of these investment projects, acting as an intermediary that will impart stability to systems that inherently lack it. Membership in the AIIB would have boosted the prospects of American investors, opening up a hitherto-closed door to continued economic growth of the US in the future. Much theorizing and evaluation of this latest miscalculation abound. But all this discussion should have come before Washington made its decision.