The People’s Constitution: How Shifts in Public Opinion Affect the Supreme Court

For some scholars (and many politicians) the independence of the judiciary is troubling in a democracy. Alexander Bickel argued that judicial review created a “counter-majoritarian difficulty” for American democracy because judges are unelected and by-and-large unaccountable, yet they have the power to overturn laws created by the duly elected representatives of the people. Of course, that was likely the Founders’ intent: as Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 58, “in a monarchy [the Judiciary] is an excellent barrier to the despotism of the prince; in a republic it is no less excellent a barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body,” precisely because it is immune to the pressures and passions of the electorate. Recent empirical evidence suggests that the Court’s decisions are responsive to public opinion – but relatively little research has explored why[1]. There’s more than one reasonable way for public opinion to affect the Supreme Court. The most obvious (and arguably most legitimate) way is that public opinion influences who’s elected to the Presidency and the Senate, and through them affects who is nominated and confirmed to the Supreme Court. There’s strong evidence for a “powerful link between constituency opinion and voting on the Supreme Court” – but other research suggests that changes in the Court’s composition might not tell the whole story (Kastellec, Lax, and Philips 2008; Giles, Blackstone, and Vining 2008).

This could also be because Justices are part of the public. As individuals, they can be influenced by the same events, arguments, and social movements that cause shifts in public opinion in the first place. As Justice Cardozo wrote in 1921, “The great tides and currents which engulf the rest of men do not turn aside in their course and pass the judge by.”[2] Supreme Court scholars refer to this as the attitudinal change hypothesis: the idea that Justice’s opinions and policy preferences are changed over time in tandem with shifts in public opinion.

The alternative, referred to as the strategic behavior hypothesis, is more intriguing. In Baker v. Carr, Justice Frankfurter wrote that the “Court’s authority – possessed of neither the purse nor the sword – ultimately rests on sustained public confidence in its moral sanction”[3]. Frankfurter suggests that justices recognize that the power of the Court rests largely on its institutional legitimacy, and may adjust their behavior accordingly. A Court that strays too far or too often from the public mood risks having its decisions rejected and under-mining the causes it sought to promote. This is precisely why Ruth Bader Ginsburg, one of America’s strongest voices for women’s and reproductive rights, argues that the Court “ventured too far” in Roe v. Wade[4]. By 1973 (the year Roe was decided) women’s rights advocates were securing key victories across the country – several states had adopted the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code approach, which allowed abortion at any state of a pregnancy to protest a woman’s physical or mental health. Only four states allowed first-trimester abortions without substantial restrictions, but public support for elective abortion was rising steadily and rapidly. Roe seemed like a decisive, game-changing victory for women, and it was. But Justice Ginsburg argues that “the sweep and detail of the opinion stimulated the mobilization of a right-to-life movement,” leading to “annual proposals for overruling Roe by constitutional amendment, and a variety of measures in Congress and state legislatures to contain or curtail the decision”[5]. By deviating so far ahead of public opinion, the Court created the organized opposition to abortion rights that ultimately undermined the policy goals they originally wanted to promote. That backlash went hand in hand with the Court’s loss of legitimacy in the aftermath of Roe as well, with conservatives arguing that judges had waded into the culture war and overstepped their authority – and as Justice Ginsburg’s essay shows, the justices are actively thinking about the backlash a Court sees when it’s misaligned with public opinion[6]. Obviously, in individual cases the justices do buck prevailing sentiments, but if this theory is true, we would expect a general trend in which Supreme Court outcomes are aligned with public opinion.

If justices are strategically responding to political pressure, or are adjusting their opinions out of fear of provoking a backlash, that has dramatic implications for how we understand the Court’s role in our three-branch democratic system and for how advocates approach impact litigation. So how can we differentiate between attitudinal change among the Justices, and a direct effect of the public opinion on the Court via strategic behavior?

The key is in the logic of the strategic behavior hypothesis, which doesn’t apply equally to every case. The Court might reasonably anticipate backlash in cases which the public is watching them closely – but in non-salient cases, to which no one is paying attention, a backlash seems much less likely. This suggests that, if the strategic behavior hypothesis is at play, we should have divergent expectations where the justices are more responsive to public opinion in salient cases; if the justices’ opinions are just shifting concurrently with the rest of the country’s, we they would be equally responsive in non-salient cases where they have reduced incentives to follow public opinion.

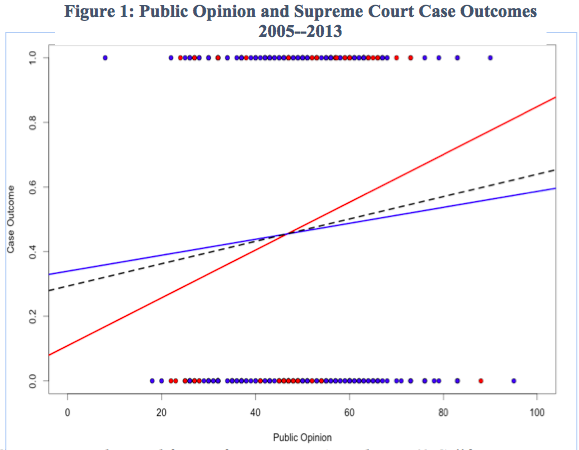

Empirical research testing the relationship between public opinion on the issues in Supreme Court cases to case outcomes shows a significant correlation between public opinion and case outcomes. But most notably, we see divergent results in salient and non-salient cases. As shown in Figure 1, we see a much higher correlation between public opinion and case outcome in high-profile cases (represented in red) with several appearances in the New York Times than to low-profile cases (represented in blue) with few or no appearances in the Times, and the full sample (represented in black). In fact, the correlation between public opinion and case outcomes in low-profile cases isn’t even statistically significant, suggesting that this relationship may only exist in high-profile cases. This strongly supports the strategic behavior hypothesis – justices appear to follow public opinion only in the cases where they have a strategic incentive to do so.

But these effects are not evenly split among the justices. A justice by justice analysis shows no correlation between public opinion and the votes of most justices. In the sample examined (all cases from 2005 – 2013) only two justices were responsive to public opinion: Justice Kennedy and Chief Justice Roberts[1]. On the Roberts Court, at least, public opinion has primarily impacted ideologically moderate Justices – the same Justices which are key swing votes on a sharply divided bench. At this stage, we can only speculate as to why that is. As likely decision-makers, they may be most acutely aware of strategic considerations; as Chief Justice, Roberts may be more concerned about his legacy and how future generations will perceive his Court’s decisions today. All of this adds up to mean that, as advocates pursue change through the legal system, trends in public opinion as a strong determinant of the high court’s final rulings, suggesting that victories for same-sex marriage, voting rights, and reproductive freedom depend not only on solid legal arguments, but also on sustained public pressure.

Notes:

[1] Justice O’Connor was excluded from analysis because of the relatively small number of cases she participated in during the sample timeframe.

Citations:

[1] Epstein, Lee and Martin, Andrew D., Does Public Opinion Influence the Supreme Court? Possibly Yes (But We’re Not Sure Why) (June 19, 2012). University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitional Law, Vol. 13, No. 263, 2010.

[2]Cardozo, Benjamin. 1921. The Nature of the Judicial Process. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

[3] Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 267. (1962) (Frankfurter, J. dissenting).

[4] Ginsburg, Ruth Bader. “Some Thoughts on Autonomy and Equality in Relation to Roe v. Wade” 63 N.C. L. Rev. 375 (1984).

[5] Ibid.

[6] See, e.g., Destro, Abortion and the Constitution: The Need for a Life-Protective Amendment, 63 Calif. L. Rev. 1250, 1319-25 (1975)