Paki-standing Alone

Over the last half-century, one of the few constants in both Pakistan and China’s ever-shifting political landscapes has been their intimate and unwavering relationship. In early 2011, Pakistan’s ambassador in Beijing, Masood Khan, vividly described the two countries’ alliance as “higher than the mountains, deeper than the oceans, stronger than steel, dearer than eyesight, and sweeter than honey.” Indeed, China has consistently championed Pakistan’s causes, whether by supporting its position on Kashmir or supplying engineers and aid to develop its economy. But why has China, a nation with a multivalent agenda and myriad of other investment opportunities, time and again poured its foreign reserves into sponsoring low-security and low-returns deals with Pakistan, an unstable economy that lacks a clear program for growth? And will Beijing continue its heavy political and economic engagement with Pakistan?

Over the last half-century, one of the few constants in both Pakistan and China’s ever-shifting political landscapes has been their intimate and unwavering relationship. In early 2011, Pakistan’s ambassador in Beijing, Masood Khan, vividly described the two countries’ alliance as “higher than the mountains, deeper than the oceans, stronger than steel, dearer than eyesight, and sweeter than honey.” Indeed, China has consistently championed Pakistan’s causes, whether by supporting its position on Kashmir or supplying engineers and aid to develop its economy. But why has China, a nation with a multivalent agenda and myriad of other investment opportunities, time and again poured its foreign reserves into sponsoring low-security and low-returns deals with Pakistan, an unstable economy that lacks a clear program for growth? And will Beijing continue its heavy political and economic engagement with Pakistan?

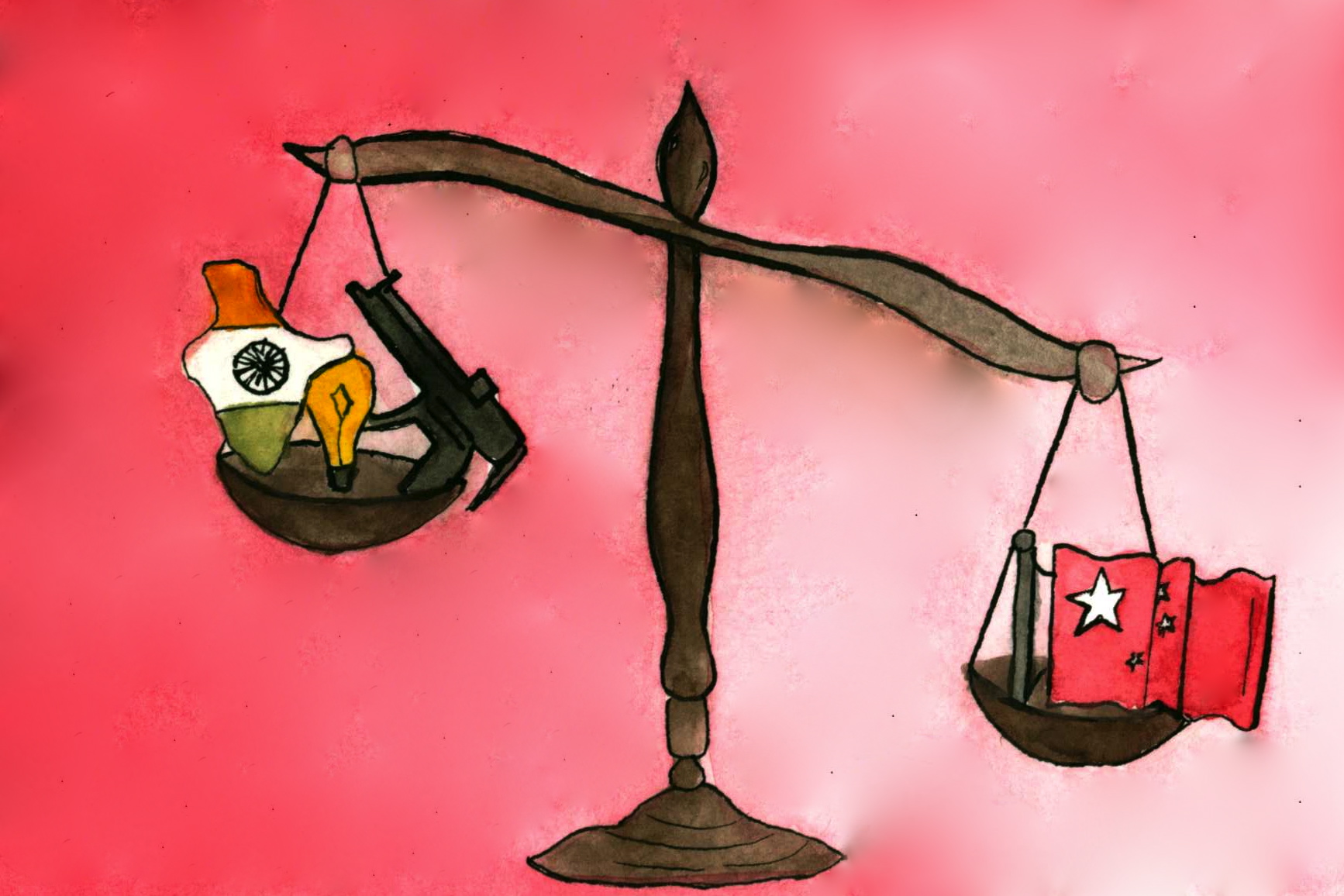

Some arguments point to increasing the distance between Beijing and Islamabad. Mutually rewarding trade partnerships between India and China have thawed the two countries’ historically frigid relations, so there is a decreasing need for Islamabad to help Beijing balance New Delhi. On the domestic level, recent violence and unrest in Xinjiang, a northwestern Chinese province, is traced back to Taliban-run camps in Pakistan where Uighur separatists are said to have trained. Moreover, the last few decades have seen China increasingly constrained by nationalistic sentiment, and less inclined to continue its famous no-strings-attached developmental aid.

Despite these new considerations, China will continue its close relationship with Pakistan as part of its security strategy. Today, a close relationship with Pakistan is valuable to China with regards to three geostrategic considerations. First, Pakistan is necessary for balancing India as it becomes more economically, politically, and militarily powerful. Second, Pakistan may play a critical part in preserving China’s energy security interests in its western territories and Central Asia. Third, Pakistani cooperation is critical in combating domestic unrest and Islamic terrorism in Xinjiang.

Without strong ideological or cultural affinities, Pakistan and China’s closeness has been largely governed by geostrategic security considerations alone. The Sino-Indian War in 1962 made New Delhi and Beijing hyperaware of each other’s proximity and ambitions for strategic dominance in Asia. Shared enmity towards India, their common neighbor, led Pakistan and China to form a ready-made alliance, beginning a multi-pronged policy of containment. First, the threat of defending two long borders in the event of a war (as opposed to one) constrained Indian military ambitions: China has been Pakistan’s largest defense supplier, and, in the words of arms-control advocate Gary Milhollin, “If you subtract China’s help from Pakistan’s nuclear program, there is no nuclear program.” Second, China’s political support of Pakistan on issues such as Kashmir prolonged the South Asian conflict, thereby slowing New Delhi down in its pursuit to become a major international player. “The Chinese government and people firmly support the righteous stand of the Pakistani government and the just struggle of the Kashmiri people for their right of self-determination,” said President Liu Shaoqi during a visit to Pakistan in 1966.

As time wore on, however, China’s notoriously elastic foreign policy did not leave Pakistan unscathed. Sino-Pakistan relations cooled in the wake of the Cold War as Beijing sought rapprochement with New Delhi. China’s Kashmir rhetoric seemed more diluted - in 1996, when then-President Jiang Zemin advised Islamabad to “put the thorny issues aside and develop cooperative relations with India in less contentious sectors like trade an economic cooperation.” In 1999, the Kargil War saw Pakistan and India skirmish in Kashmir. Rather than maintain its usual support for Pakistan, China was critical of Islamabad’s violation of the Line of Control and adopted a deliberately neutral position on the conflict. It seemed as if Sino-Pakistani relations were losing their durability.

Other considerations have also tempered Beijing and Islamabad’s allegiance. Pakistan plays a significant role in the domestic unrest and instability of western China. Xinjiang, China’s largest and most energy-rich province, is home to a majority Uighur population, a predominantly Turkic Muslim people. Ethnic assimilation by migrating Han Chinese, diminishing political autonomy, and socioeconomic marginalization led to major discontent in the 1990s as Uighurs violently protested. After the opening of the Karakoram Highway, which links Kashgar, the historical and cultural center of Xinjiang, and Pakistan’ s capital Islamabad, many Uighurs travelled to Pakistan for religious instruction. Actually , some of these Uighurs trained at Taliban-run camps, and returned back to Xinjiang with plans to fight the perceived Chinese oppression with terrorist tactics, targeting civilians and detonating suicide bombs. Consequently, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), a militant separatist organization with strong links to Al-Qaeda, was founded, though the CCP has ruthlessly tried to squash it. Suspicious that Pakistan has been sympathetic towards such Uighur quasi-Islamic separatist movements, Beijing has punished Islamabad accordingly. In 1992, after a failed Islamist uprising in a town near Kashgar that saw 22 people killed, China closed its road links with Pakistan for several months and tapered the aid it had been sending.

Beijing’s direct development also may no longer be so forthcoming due to emerging constraints on Beijing’s foreign policy. Domestic nationalist pressures forced the Chinese government to launch a large-scale evacuation of tens of thousands of Chinese citizens from Libya in 2011. Chinese nationals in Pakistan have also come under heavy attack in recent years. In 2004, a bombing in Baluchistan killed three engineers, and more recently Chinese workers have also been kidnapped increasing frequency. Pakistan has high hopes for China to back the construction of rail and road links from Kashgar down to Gwadar, a port by the Arabian Sea, but it is difficult to see whether China will take on the heavy risks of construction in Baluchistan, Pakistan’s most unstable and ungoverned province. Similarly, in September 2011, China Kingho Group, a mining behemoth, pulled out of a $19 billion deal that would have been Pakistan’s largest ever direct foreign investment. In 2008, Pakistan was even forced to turn to the International Monetary Fund when China did not deliver the comprehensive bailout package it had attempted to solicit.

Despite this apparently growing schism, Hu Jintao still described Pakistan as an “indispensable partner” during his presidential visit to the country in November 2006. In December 2010, Premier Wen Jiabao remarked that Beijing would “never give up” Islamabad. What drives such exclamations of solidarity and loyalty? Since the turn of the 21st century, Pakistan, in exchange for diplomatic and economic support, has performed three functions that are crucial to preserving China’s national security.

Pakistan’s role as a balancer has gained new vigor since 9/11. Previously, Pakistan and China had simply drawn mutual benefits from a military balancing maneuver against India, but after 2001 Pakistan became crucial in balancing both the United States and India’s strengthening relationship with them. In retaliation for the US-India Next Steps in Strategic Partnership (NSSP) in 2004 and the US-India Civil Nuclear Agreement that soon followed, the China National Nuclear Corporation signed an agreement with Pakistan for two new nuclear reactors, in addition to the two it is already working on. This move was in clear violation of the Nuclear Suppliers Group guidelines involving NPT non-signatories, but China justified its action on the basis of “compelling political reasons concerning the stability of South Asia.” Moreover, from a Chinese perspective, US intervention in Afghanistan post-9/11 was a preliminary step in its long-term strategy in Central Asia. This may not be far from the truth: The Pentagon’s 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review identified Central Asia as a “new strategic crossroad,” and the US already has a military base in Kyrgyzstan and is pushing development efforts there as well. For China, Pakistan may be crucial to halting further US advances into the region as a bridge between the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Persian Gulf countries. If Sino-US interests clash more directly in the region, a future military base in Pakistan will match proposed US military bases in India.

Maintaining energy security is a core feature of China’s larger security endeavors. China is the world’s largest energy consumer and producer in the world, and Pakistan serves its larger ally’s energy objectives in two ways. First, Pakistan’s coast lies close to the Strait of Hormuz, and could be the location of a future naval base to protect China’s energy supplies, especially given the presence of US Navy patrol ships in the region. Second, Pakistan could function as an alternative energy corridor channeling oil and gas from the Middle East to western China.

This second role is most apparent in China’s heavy investment in Gwadar, a constructed port city at the mouth of the Persian Gulf. Gwadar’s strategic importance is so cons i d e r a b l e that the US report e d l y “tried to out-price the Chinese to take over the entire facility.” Pan Zhiping, Director of the Central Asian Studies Institute at the Xinjiang Academy of Social S c i e n c e s , describes Gwadar Port as “China’s important energy transfer station” and “China’s new energy channel.” A Pakistan-based oil and gas passage to western China would be a quicker and safer route than the passageway through the South China Sea, where China has recently sparred with the United States, the Philippines, Vietnam, and India over territorial disputes. As the Karakoram Highway is expanded and Qinghai-Tibet railway is constructed, an energy corridor starting from Gwadar seems more and more likely.

The advancement of an energy corridor through Pakistan would also serve another of Beijing’s goals: the development and restraint of Xinjiang as part of the larger effort to control western China. Although Pakistan’s inability, if not reluctance, in fighting ETIM contributed to the instability in Xinjiang, Pakistan’s cooperation in combating this real and potent threat to stability in economically important western China is critical. ETIM members are both trained in Pakistan and funded by sympathetic groups, and China has pushed for the Pakistan government to crack down hard. In 1997, 14 Uighur students were deported and in 2001, then-President Musharraf told then- Vice President Hu Jintao, “Pakistan will wholeheartedly support China’s battle to strike against the East Turkestan terrorist forces.” These efforts have gained results: In May 2002, the Pakistani military was reported to have detained Ismail Kader, a major Uighur separatist leader, and Hasan Mahsum, founder and leader of ETIM, was also killed in a Pakistani military sting operation in December 2003.

China’s calculus in Pakistan may be continually evolving, but long-term geostrategic security remains the objective on which China cannot and will not compromise. Rather than reacting to a weakening, unpredictable Pakistani state by severing ties, Beijing will probably scale up its efforts and institute “tough love” policies to meet its needs. Of course, China is still extremely cautious in its efforts to balance US-Indian relations as it does not want to overtly aggravate either party— previously, Pakistan suggested China could use Gwadar as a naval military base, a proposition that Beijing immediately rejected.

Pakistan’s strategic importance to China does not guarantee harmonious relations—Beijing has the power to waggle the carrot or wield the stick. In early March, eight men and women attacked the central train station of Kunming, the capital of the southwestern province Yunnan. Armed with knives, these people slaughtered 28 civilians and left 130 injured in what the Chinese media have dubbed “China’s 9/11.” As pressure mounts on Beijing to react swiftly, Islamabad must do all it can to ensure that Beijing, its most powerful ally, does not lose faith but remains, in the words of former President Pervez Musharraf, a “time-tested and all-weather friend.”

Zan Gilani, CC `15, is from Karachi, Pakistan and double majoring in Political Science and East Asian Studies. He is also the president of the Growth and Development Project at Columbia University. He can be reached at: shg2113@columbia.edu