Warrants for Torrents

When H.R. 3261 was introduced in Congress in the fall of 2011, it generated relatively little commotion. The seemingly innocuous bill, intended “To promote prosperity, creativity, entrepreneurship, and innovation by combating the theft of U.S. property, and for other purposes,” was immediately referred to the House Judiciary Committee for discussion and further debate. On November 16, the one and only public hearing for the bill was held wherein a panel of witnesses, mostly supporting the bill, testified to its merits.

When H.R. 3261 was introduced in Congress in the fall of 2011, it generated relatively little commotion. The seemingly innocuous bill, intended “To promote prosperity, creativity, entrepreneurship, and innovation by combating the theft of U.S. property, and for other purposes,” was immediately referred to the House Judiciary Committee for discussion and further debate. On November 16, the one and only public hearing for the bill was held wherein a panel of witnesses, mostly supporting the bill, testified to its merits.

In the following months, however, the “Stop Online Piracy Act” (SOPA) became a household name. At its core, the bill threatened internet users and website owners alike by essentially nullifying so-called “safe harbor” provisions which protect users from criminal liability for uploading copyrighted material. By January 2012, major internet companies such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter had come out against the bill, while popular websites like Wikipedia even went as far as shutting down for an entire day in protest. Up until that time, no other piece of copyright enforcement legislation had received the amount of attention that SOPA did.

What made this even more astonishing was that almost identical bills had been introduced before and during SOPA’s life in Congress. The PROTECT IP Act (PIPA) was SOPA’s counterpart in the Senate, itself a rewrite of a bill from a year earlier called the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA), which also shared many of the provisions of these newer bills. Additionally, these bills shared the strong blessings of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), the lobbying arms of the entertainment industry and major players in the effort to combat online piracy. Although these bills were ultimately defeated, their combined lobbying efforts and close relationships with lawmakers have allowed the RIAA and MPAA to continue seeking stronger powers of enforcement over their copyrights. In fact, these organizations have already managed to create their own private system of enforcement that mimics many of the provisions proposed previously in legislation, but without any public oversight. The debate over copyright enforcement did not stop with SOPA’s defeat. In fact, a greater threat is emerging as a result.

The MPAA and RIAA are actually trade associations founded to advance the common business interests of their members and to promote technical standardization. Currently, membership in the MPAA consists of the “Big Six” film studios: Walt Disney Studios, Sony Pictures Entertainment, Paramount Motion Pictures, Fox Ent e rtainment Group, NBCUniversal, and Warner Brothers Entertainment. Similarly, the RIAA represents over 1600 record labels around the country, with a majority of its board of directors coming from the “Big Three” music companies: Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group and Warner Music Group.

Since Napster was sued in 2000, both associations have taken a frontline role in combating online piracy. Starting in the late 1990s, the RIAA began suing large file-sharing sites, including the infamous Napster, which the RIAA claimed “facilitated the piracy of music on an unprecedented scale.” Since then, the RIAA also took upon itself to sue the makers of Limewire and Kazaa, file-sharing sites that flourished in the absence of Napster during the mid- 2000s. During this time, however, the MPAA and RIAA increasingly started filing lawsuits against individual file-sharers. This was an expensive endeavor, as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) shielded the identities of many subscribers from subpoenas revealing their identities. Because of this, in the RIAA’s case, defendants were offered an average settlement of $3,000, payable to the RIAA directly, which could balloon up to $9,000 per song.

This approach continued until December 2008, when it was dropped due to its apparent ineffectiveness in stopping the growth of file-sharing activity online. According to the RIAA’s president at the time, the mass lawsuits had “outlived most of their usefulness.” But not all of the MPAA and RIAA’s tactics were focused solely on litigation; both associations invested heavily in publicity campaigns to convince people to stop willfully sharing copyrighted material. Among these campaigns is the famous “You Wouldn’t Steal a Car” video, which was played in many theaters before movies as well as on DVDs. The video likened piracy to petty thefts such as stealing a handbag and more serious crimes like stealing a car. While the effectiveness of these efforts was inconclusive, educational programs such as these were much maligned in the press and popular culture. Despite these minor setbacks, the media industry continues to spend time and money combating online piracy due to the apparent threat it poses to their industries.

Domestically, the movie industry generates just over $10 billion annually in revenue, while the music industry generates around $7 billion. With such large stakes involved and current methods appearing ineffective, the industry players are looking more and more toward Capitol Hill to alleviate their concerns.

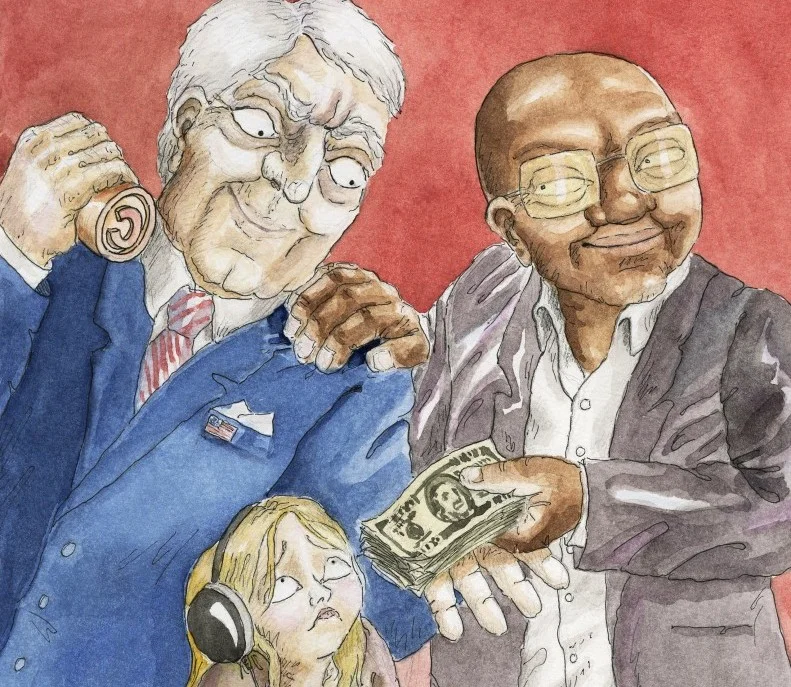

In 2012, the MPAA spent $1,009,744 on contributions to candidates, political action committees, and Section 527 organizations, as well as $1,950,000 toward general lobbying efforts. In the same year, the RIAA spent just $349,293 on contributions but a massive $5,068,287 on lobbying efforts. Both associations also rely heavily on the “revolving door” practice where former legislators and other government personnel take jobs lobbying in the same industries they were once charged with regulating. Most notably, the the MPAA president is Chris Dodd, the former chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, who assumed the role promptly after leaving office in early 2011.

Due to the media industry’s presence in southern California, a large amount of the direct contributions made to candidates on behalf of the MPAA and RIAA go to local politicians. In 2012, Senator Dianne Feinstein of California received over $16,000 in contributions from the two associations and former Representative Howard Berman of California’s 28th congressional district received just over $24,000 in the same period. During Representative Berman’s time in office he was sometimes known as the “congressman from Hollywood” due to his close ties with the media industry that resided mainly in his district. Berman was a key co-sponsor of SOPA when it was introduced and even sponsored his own piece of legislation in 2002, “To amend title 17, United States Code, to limit the liability of copyright owners for protecting their works on peer-to-peer networks.” Essentially, this would have allowed copyright owners to manipulate content-sharing networks to prevent further distribution of copyrighted content. The bill quickly died in committee, but his sponsorship helped further cement his strong connection to the media industry. In Senator Feinstein’s case, she was listed as a co-sponsor of PIPA and vocally supported it.

While the MPAA and RIAA contribute money under their own names, the constituent members of these associations also contribute significantly to candidates directly. Representative Lamar Smith of Texas, who introduced SOPA in the House, received a total of $147,050 from the media industry during his 2012 campaign, the highest amount donated from any one industry to his campaign. In the same period, Senator Patrick Leahy, who introduced PIPA and COICA in the Senate, received about $570,000 from the media industry, for his campaign and through his leadership PAC, making it his second-largest source of donations.

In recent years, many of the copyright enforcement bills proposed by lawmakers have contained a significant number of controversial provisions that give greater enforcement methods to copyright owners while dampening many of the protections that website users and owners have historically received. Most controversial are the provisions that hamper so-called “safe harbor” protections, which protect sites on the internet from liability for user-uploaded content, provided that the site removes the content in a reasonable amount of time. One of the biggest controversies regarding SOPA was its transfer of liability from content owners (who always need to request content to be taken down) to the content host, who under the new law would be required to actively monitor any user-generated content for copyright infringement and take proactive measures to remove the content in question.

If infringing content did indeed make it onto a site, a single complaint from the copyright owner could invoke the harsher provisions of the bill, which include the automatic takedown of the site as well as a freeze on all payment and advertising sites doing business with the site. These complaints can be challenged, but doing so requires proving that the copyright owner knowingly filed the complaint in error. While these tactics seem somewhat excessive given that most infractions were historically civil matters, the most dramatic might be the automatic takedown of websites from the internet.

For the technically unaware, a major component of the web’s infrastructure is what is known as the Domain Name System (DNS). DNS essentially functions as a phone book, translating human-readable names like Google. com into I n t e r n e t P r o t o c o l (IP) addresses which facilitate communication between computers. Currently the DNS infrastructure relies on a fair degree of trust that certain providers will always give back truthful responses. Extending the metaphor, SOPA allowed the government to control the master phone book, thereby giving it the ability redirect users away from sites thought to be hosting infringing content. This essentially functions as an internet blacklist, which in theory could block any website from being accessed domestically. Such tactics are already common in countries such as China, where the “Golden Shield Project” employs DNS redirection from censored sites that have been deemed controversial by the government.

Many of these mechanisms give content providers judicial powers when it comes to combating internet piracy. Instead of needing to send a court order directly to a website owner, content providers would merely need to file a complaint with the appropriate agency for immediate effect. Such heavy-handed tactics may benefit the media industry, but impose a rather significant cost on users and website owners alike. Provisions such as the stricter “safe harbor” rules would make running small user-content sites almost impossible due to the legal need for self-policing, which can be extremely resource intensive. Additionally, there would be a persistent fear of liability if a mistake were to be made in the censoring process. It can also be a liability to investors who might be wary of or otherwise choose not to invest in smaller companies out of fear that complaints could quickly sink the business.

Going beyond economic costs, these new provisions threatened to undermine freedom of speech online. SOPA and PIPA were heavily criticized for the provision that made it illegal to even link to sources of infringing content, essentially opening up every user on the internet to liability if they were to knowingly or even unknowingly share a link to a piece of content that was deemed to be infringing. Even ignoring all of these apparent problems, a heavy-handed approach to policing content may not be the most beneficial given the uncertainty regarding economic losses that piracy actually causes. An expert interviewed in the Government Accountability Office reported in 2010 that the “effects of piracy within the United States are mainly redistributions within the economy for other purposes and that they should not be considered as a loss to the overall economy.” This is not to say that piracy should be condoned, but rather the scale of the problem is not as large as proponents make it out to be. In fact, many studies put out by the media industry have been consistently debunked and shredded by outside organizations. But despite the opposition, the media industry is still very much set on moving forward with its agenda.

While many of the bills backed by the media industry were defeated, there is still a risk posed by the possibility of their re-emergence. A significant reason why these provisions are struck down is a lack of precedent or comparable situations. In the previous decade, very little copyright legislation was proposed and it was not until 2010 that many of these new, controversial copyright bills started to emerge. Slowly legislators are starting to treat these controversial provisions as the “new normal” in proposed copyright legislation, rather than the exception. Future legislation is more likely to include these provisions in one form or another because of the precedent set by their constant presence in other bills.

A shift in focus is occurring from the problem itself to specific, allowable enforcement methods. But what is left out of the debate is the essential question of what are the fair and equitable punishments for copyright infringement. RIAA settlements frequently hover around $750 per song, but according to US copyright law, the fine can be up to $30,000 per infringement. This massive cost seems unreasonable in light of the crime committed, but, to the benefit of copyright owners, remains the status quo. The fairness of such repercussions should be discussed, lest users be exposed to potentially huge liabilities. In normal situations, charging large fines might be an equitable solution to the problem, but online piracy is unique in that it is widely practiced and is generally looked upon by those who participate as a crime without victims. Online piracy is arguably a different beast than other forms of theft, but lawmakers have shown that they would rather give away the powers of enforcement directly to the copyright owners than deal with the underlying problems head-on.

Given the defeat of recent anti-piracy bills, copyright owners are looking to obtain many of the powers through other, more opaque procedures. In February, five of the top internet service providers (ISPs) joined together with copyright owners such as the RIAA and MPAA and created the Copyright Alert System (CAS), which allows the direct punishment of internet subscribers who commit copyright infringement. From the perspective of copyright owners, the system is much more efficient than the mass lawsuits of the previous decade since none of these cases are required to go through the judicial system. Instead, users who choose to appeal a ruling are forced to confer in private with an arbitrator chosen by the ISPs. It is the arbitrator’s responsibility to decide whether a given subscriber is responsible for the infringement or not.

Possible punishments for those found guilty of an infringement are warnings, bandwidth throttling, and even mandatory education programs that will re-activate a user’s connection upon completion. It is through the inaction of policy makers that such systems are allowed to exist. The perpetual avoidance of creating a proper system for dealing with online piracy means that average internet users are increasingly subject to unfair private systems that are not required to be transparent about their actions. The neutrality of these mandatory arbitration meetings have also been called into question, considering they are set up and paid for by the participants of the system. What would have historically been a judicial matter involving a judge and attorneys is now handled in private without any third-party oversight and or additional appeals process.

The media industry has continually shown that they still view such powers as essential to their fight on privacy. Their relationships with lawmakers have created a culture of inaction that allows them to assume these powers through the use of private agreements. What is lost in the process is a certain sense of fairness now that users are beholden to arbitrary rulings without public oversight. SOPA and other copyright bills may have been struck down, but the MPAA and RIAA still represent a threat to the internet-using public. As long as these relationships continue, it might be the case that these practices become enshrined in law, or that even stricter enforcement methods are implemented. Online piracy is an important global issue that needs to be handled by public legislators, but must be treated differently from other forms of theft.