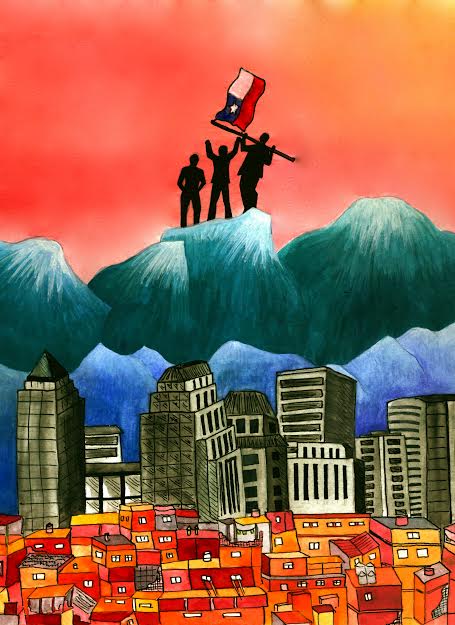

Red Hot Chile-crats

With its unique history, culture, and geographic diversity, Chile provokes the interest of observers and analysts. Yet, it is one of Chile’s more scarcely commented upon features − its outlandish political system− that has great potential to yield some truly valuable insights.

With its unique history, culture, and geographic diversity, Chile provokes the interest of observers and analysts. Yet, it is one of Chile’s more scarcely commented upon features − its outlandish political system− that has great potential to yield some truly valuable insights.

A function of its tumultuous recent past, Chile’s political set-up possesses many unusual features. The country remains the only one with a binomial electoral system, a strange mechanism designed such that every electoral district chooses two representatives instead of one. In any given election, both the winning candidate and the runner-up candidate win one seat each, except in the unlikely event that the winning party routs the second party by securing more than double its share of votes.

This bizarre set-up means that the two main (and only) political adversaries in the country, the Allianza and the Concertacion blocs, almost always occupy the same number of seats in the legislature. As a consequence of a very predictable political order that all but guarantees politicians their seats, Chilean leaders are insulated from large electoral shocks and have clustered into a tightly knit, elite community. Less constrained by populist pressures, Chile’s leaders feel free to appoint theoreticians and academics to posts of political power to manage the country’s affairs. This contributes significantly to a defining feature of Chile’s political landscape: the deep influence and prevalence of what political scientists would generally deem a technocratic class.

The hallmarks of such a class generally include a body of highly trained, specialized individuals who participate in the political system of a nation under the conviction that policy is better managed through exacting, scientific principles. Although technocrats are usually defined as being in staunch opposition to career politicians who manage everyday party politics, many of Chile’s elected leaders can nevertheless be included in this definition because of their academic preoccupation with policy minutiae, and the relatively small electoral and political duties they carry given the stability of Chile’s electoral set-up.

Though such technocratic features are relatively rare across the world, Chile is by no means the only nation to lay claim to such a political system. A variety of nations as varied as France and Singapore possess some elements of a technocratic government. What truly sets Chile apart is the degree to which its technocratic class has been influential, unfettered, and resilient. Chilean technocracy has enjoyed an unprecedented free reign within political institutions, enabling reformers to suggest and enact some truly revolutionary ideas. Furthermore, this group, with origins stretching back to the 1920s, can also claim the distinction of having survived under different constitutions ruled by both authoritarian and democratic regimes. These features of the Chilean technocracy make it an outstanding case to understand how the almost Platonic ideal of a highly trained political class handles the ground realities of managing a nation. The lessons to be learned offer wisdom on how countries around the world can reform their own institutions, and to what degree a positivist, non-political approach towards running a nation can succeed.

The Chilean political historian Patricio Silvia offers us valuable insight into the emergence of this type of polity, which can help us analyze and answer some of these questions. The true development of a body of influential economists and industry experts in policymaking occurred for the first time in the early 1930s under a government led by the political strongman Colonel Ibáñez. Presiding after a long stretch of political ineptitude, Ibáñez appointed a radical cabinet, filling positions with individuals who were completely new to politics, but were nevertheless prominent and well established in their own fields of public action. The idea was to create a new, modern Chile by eliminating government inefficiencies and replacing petty political rivalry with scientific management. To this end, Ibáñez then appointed the highest and most reputed Chilean engineers and technical experts to key ministries, in order to create the most conducive environment for a Chile that was now the site of a major renovation project involving rail, road, medical, and educational infrastructure.

As Ibáñez’s rule came to an end in 1932 amidst the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, the effect of the technocratic class persisted. The experts of the Ibáñez period continued to propose many ambitious projects long after the colonel’s fall, despite the prevalence of a shifting political climate that saw more governments fall in and out of power than any point in modern Chilean history.

As the decades rolled on, a new kind of expert appeared on the Chilean scene. The focus on competing economic systems brought about by the Cold War, as well as the emergence of developmental economics, meant that economics had become the latest field of technical proficiency that promised decision makers an efficient way to direct government. As Chile took a turn towards socialist government in the 1960s and 1970s, an assortment of pro-state intervention economists from a UN think-tank called the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Carribean, led by the Argentine economist Raul Prebisch, gained tremendous credibility within the ruling regime. His group’s academic justifications for protectionism and nationalization became incredibly influential in the new government’s manifesto of the “Path Towards Socialism.” The ruling Popular Unity government attempted to overhaul labor relations and the crucial mining sector, and reorganize market forces, but soon found its efforts stymied by stiff political opposition. When neither the government nor the opposition relented, a crippling political and economic paralysis engulfed the nation for three years.

It was against this political backdrop that the watershed event, which has come to define Chile’s recent past, came to pass. Led by General Augusto Pinochet, the heads of the Chilean armed forces staged a quick, but bloody, coup that toppled the socialist government of President Salvador Allende in September 1973. Along with many other important changes, the coup brought about a drastic transformation in the political status and influence of Chile’s technocrats. It is this legacy that continues to affect Chile directly up to the present day, and serves as a powerful lens through which we view the operations of Chile’s government. Pinochet’s junta highlighted the role of technocrats as never before, granting these experts prominent positions within the regime’s policy organs. During these years, they became a crucial instrument of political control and legitimacy, also taking on the roles of government ideologues and power brokers.

The group of elites that came to play this role initially stumbled on the path towards influence after a little known event in 1955, when the Economics Department at the Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) in Santiago signed a long-term partnership with the University of Chicago. The program came at a fortuitous time for PUC, just as its American counterpart was making waves for a radical new brand of economic neoliberalism. Within a few decades, the elite batch of students who were all pursuing advanced degrees in economics at PUV had fallen under the direct or indirect tutelage of the celebrated free-market champion Milton Friedman. When Pinochet overthrew the Allende government, it was this group of academics, vehemently opposed to socialism, which was elevated to the regime’s most trusted ring of advisors.

Well aware that the legitimacy and survival of his highly repressive rule depended on financial stability in Chile, Pinochet was alarmed by a series of economic setbacks that developed just as he took power. He quickly granted these new experts – or the “Chicago Boys,” as they proudly identified themselves – a sweeping range of policy powers to take whatever course of action was required to rectify the situation. Under Pinochet’s aegis, these academics rapidly turned the State Planning Agency (ODEPLAN) into their bastion, occupying key positions and leadership roles.

In 1975, they successfully advocated for a radical program of privatization, absolving the government of responsibility over health care, infrastructure, utilities, and social security. Schools were made independent from the state, and the government withdrew its hand over industry. Tariff rates and protectionism, traditionally high in the region, were rapidly reduced. The Chicago Boys took over top government positions in the Cabinet and other agencies dealing with agriculture, labor, health, social security, mining and unsurprisingly, finance, budgeting, banking, and taxes. Whatever the reality may have been, the group imagined itself as impartial guardians overseeing the free markets and preventing the manipulation of rules by vested interests. The influence and visibility of the Chicago Boys grew to such an extent that they were even able to organize for Pinochet to meet Friedman, after arranging his attendance at a conference presided over by many other neoliberal notables.

Despite the ostensible success of the Chicago Boys, actual economic conditions in Chile barely improved after Allende’s fall. By the early 1980s, the Chilean economy entered a painful period of transition as it struggled to adjust to the “shock-therapy” of sweeping reforms imposed upon it from the top by the Pinochet leadership. Financial institutions went under, foreign lenders thinned, and year-on-year output tumbled by 14 percent in 1981. Pinochet quickly restocked his cabinet with more pragmatic economic mangers. Hernan Buchi, a Columbia-educated economist, was chosen for the job of finance minister. Despite his similar, heavily academic background, Buchi rose to the occasion by using a less radical mix of laissez-faire policies in what has since been labeled pragmatic neoliberalism. He succeeded marvelously, and was able to place Chile firmly on the path of stable and impressive economic growth it has sustained for over 30 years since. Regardless of Chile’s long-term recovery, Pinochet was forced by the 1981 crisis, as well as stricter global scrutiny over human rights, to concede more and more political freedoms to a nation he had once run with an iron fist.

As the former underground opposition to the Pinochet regime grew in visibility and strength, not only the General, but also his advisors, came under fire. Quite notably, one of the first types of subversive activity carried out by the opposition was actually the establishment of rival think tanks and academic institutions that challenged, officially, the Chicago Boys’ claims of economic success. The most renowned of these, CIEPLAN, continues to operate today and advises the Center-Left Concertacion coalition. The opposition (later to become the Concertación) used grassroots movements and human rights issues to win over support, but it is telling that they first formulated their opposition to the regime as an academic challenge.

Ultimately, Pinochet was forced to bow down to growing public pressure and face a negotiated settlement that would determine the future of his regime. In 1989, he lost a referendum held to decide whether his rule would be prolonged, with 56 percent of the general population voting against him. The new democracy that had been brokered saw the governing left-wing Concertación face up to the daunting task of reconciling a Chile polarized into pro- and anti-Pinochet camps. One problem it did not face, however, was overhauling economic policy. Despite the radically right-wing stance taken by the Chicago Boys, Chile has remained a place where the principles of free market and private enterprise enjoy broad support across the political spectrum and the public. For the most part, the differences between the Chilean left and right do not concern broader economic policy. Mostly, they reflect minor technical differences between different versions of the same measure. Years after the transition to democracy, government spending in Chile remains among the lowest for its income level, and most of the economy lies in private hands.

Given the absence of significant, radically-opposed policy issues across political parties, it is unsurprising that another feature of Chilean politics to survive the authoritarian regime would be the prominence of the technocratic class. Although Chile’s political rulers must now either be elected or appointed by elected officials, little has changed with regard to the rule by experts. Graduates from Ivy League schools and other top global institutions occupy the upper-echelons of the political classes. Democratic Chile’s first finance minister was none other than the head of the think tank CIEPLAN, and the President’s small economic team was filled with alumni from leading institutions in the United States such as Harvard, MIT, and the “Oxbridge” colleges in the United Kingdom. Despite recent and occasional rumbles about a more representative and less technocratic government that would encapsulate the majority of Chileans, it seems that little has changed in Chile.

Among its successes, Chile’s technocracy can count a dazzling economic track record, lifting it from the ranks of impoverished countries to a high-income economy in just a few decades. Economic growth has hovered consistently around five percent for the past two decades or so, Chile’s public finances are in shape, and its monetary system runs smoothly. Educational enrollment has seen a meteoric rise across all categories, with high school participation on par with nations like France. Absolute poverty has been eradicated, despite being over 30 percent in the 1990s, and relative poverty is on a path of steep downward decline. On the whole, government officials are considered scrupulously honest and generally efficient.

Chile’s apolitical economic oversight has also meant that it was able to gradually create a framework of stabilizing reforms and savings that isolated the country from financial turmoil and the collapse in commodity prices during the financial crisis of 2008. These countercyclical measures were enacted despite vested interests that stood to gain from riding the pre-recession boom and would have likely had the clout to block such reforms in most other countries. The government’s brainy group of advisors has also allowed Chile to succeed where many other nations have tried and failed – particularly in the development of increasingly successful and viable innovation hubs. The aforementioned CORFO now deals specifically with the purpose of stimulating innovation through a market system, and has proven incredibly adept at the task, becoming the envy of many other aspiring governments.

But the Chilean political class must also face up to its shortcomings. Chile has been staggeringly ineffective or unwilling to deal with the tremendous inequality generated by rapid growth and free markets, and is behind only a handful of other large nations by GINI coefficient, a statistical measure of income inequality. Problems associated with distribution of wealth stem largely from the state’s inability to ensure high education standards for the masses, and the absence of large state-welfare programs. The legacy of education privatization and municipalization under the Pinochet years lives on to haunt a Chile unable to lift its most impoverished communities to a level playing field. Ironically, because of the domination of and malpractice within the large private sector in education, Chile’s disadvantaged end up paying far more for a college education than wealthier communities while earning a less prestigious degree. College loans add a massive burden to the lives of students who struggle to find high paying jobs. These inequities have often led frustrated students out into the streets of Santiago in protests that have brought the nation to a standstill repeatedly in the past decade.

Accompanying this outrage is a troubling decline in public confidence in Chilean leadership. Turnout at the polls, especially amongst the youngest generation, has been steadily falling. The last presidential poll in 2009 saw a dismal 9.1 percent turnout of 18-to- 29 year olds registered to vote. The common perception on the street and amongst the youth is that the elite, political-technocratic class governs the country from an ivory tower and fails to understand the plight of ordinary Chileans. The incredible wealth and close connections of members of the tiny political elite are scorned as signs of perpetuation of self-serving system. Disillusionment with the binominal system and similar institutions that benefit Chile’s two electoral blocs and favor incumbents further add to Chileans’ weariness.

Chile’s most recent major political event – the just concluded first round of the presidential race for 2014 – offers a breath of fresh air, short though it may be. After cruising to victory in the preliminary stage, socialist ex-President Michelle Bachelet of the left wing Concertación is all set to rout her right-wing opponent Evelyn Matthei in the December runoff race. Bachelet previously rose to the presidency in 2006, on the back of promises of deep social reform of the free markets, “no a los technocratos,” and the rare charisma of a people’s person in otherwise staid political circles. Despite embarking on bold socioeconomic reforms, such as state-guaranteed basic pensions and child support for the poor, Bachelet was unable to fulfill her larger promises to upend the elite political order and slash poverty and social inequality.

Furthermore, public frustration also erupted during her first term (2006-2010), when the now infamous student protest movement first gained its foothold. When Bachelet left office in 2010 (Chile has a single presidential term limit), she was neither able to do away with the technocracy, as much of her team was composed of a Chile-centric, Harvard-based think tank, nor keep her promises of deep socio-political and economic change. Although the minority of Chileans who voted were and continue to be overwhelmingly dazzled by her charisma and resolve, Bachelet’s real popularity challenge lies with the protestors on the street who believe her to be just another politician in a highly manipulative and unresponsive system. To add to the wellspring of dissatisfaction, many political analysts believe her promises to bring change to Chile will once again be stymied. Even if her stated policy to raise corporate taxes to 25 percent is passed, her proposal on free higher education will face a stiffer battle, and her dreams of constitutional overhaul will likely remain unattainable in the face of a conservative polity. Whatever Chilean voters may think, the viewpoint of the disenfranchised masses is loud and angry, summed up by a banner outside one of Bachelet’s rallies “Change is not in La Moneda [the presidential palace] but in the streets.”

A cursory glance at Chile’s political history has much to offer, detailing the breathtaking capacities of a government run on scientific principles by able experts. The promise of technocracy to deliver policies that operate seemingly free of partisan consideration and in the face of vested interests presents a refreshing vision of government. Seductive as rule by philosopher-kings might appear, we must be aware that technocrats are only as good as their ideas. Today’s brand of Chilean technocrats face defeat if they do not morph to address the challenges of contemporary Chile: inequality and exclusion. And the frustrations of the Chilean electorate must be better represented amongst the governing upper classes to ensure that their voices are not forgotten in treating governance as a theoretical economic problem. Perhaps, for a change, this corner of the world might actually fare well with a small dose of populism.