With Arms Wide Open: The Threat of Iranian Arms Trafficking

In February, the United States Navy and Yemeni security forces seized a shipment of allegedly Iranian-made shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles heading to Houthi insurgents in Yemen. Far from a one-time incident, it is symptomatic of a larger and more disturbing trend in the region. Through the Quds force—a mix of an intelligence agency and special forces— Iran has begun providing significant support to various groups across the Middle East. The immediate origin of Iran’s renewed attempts to export its revolution lie in its rather awkward and precarious strategic position.

In February, the United States Navy and Yemeni security forces seized a shipment of allegedly Iranian-made shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles heading to Houthi insurgents in Yemen. Far from a one-time incident, it is symptomatic of a larger and more disturbing trend in the region. Through the Quds force—a mix of an intelligence agency and special forces— Iran has begun providing significant support to various groups across the Middle East. The immediate origin of Iran’s renewed attempts to export its revolution lie in its rather awkward and precarious strategic position.

During the American occupation in Iraq, Tehran faced the reality that “the Great Satan” had military forces on both borders. Across the Gulf lies Saudi Arabia, another ideological and geopolitical rival. In Afghanistan, the Taliban are enemies of the United States yet also enemies of Iran. Indeed, Afghanistan is one of three countries—including Iraq and Pakistan—that could potentially destabilize, inundating Iran with refugees and threatening its overall security. Arguably, Iran’s civilian nuclear program, and their alleged nuclear weapons program, is one strategy of ensuring their own security. Nevertheless, since the start of the new millennium, Iran has also provided varying levels of financial and military support to both state and non-state actors in the region in an effort to create a network of alliances that will secure its national security and preserve Tehran’s regime.

Historically, Iran’s biggest threat has been Iraq, and that continues to be the case today. Saddam Hussein’s regime undoubtedly caused more damage and inflicted more loss of life in the Islamic Republic during the Iran-Iraq War than anything inflicted by the United States. The loss of life was in the hundreds of thousands on both sides, and the psychological scar this war inflicted on Iran has important policy considerations. Despite being, like Iran, a majority Shiite country, Iraq has a demonstrated ability to cause significant harm to its eastern neighbor. Thus, Iranian national security policy will do all it can to prevent a powerful Iraqi government. In the 1990s, this was easy: Saddam suffered a tremendous blow from the 1991 Gulf War and throughout the period, the United States and its allies were enforcing a no-fly zone and sanctions. Iraq was, from Iran’s perspective, neutered.

When the US military toppled Saddam’s regime in 2003, all bets were off. Operation Iraqi Freedom changed everything, and assuming Iraq would no longer be a threat was no longer an acceptable policy. At worst, the United States could have completely succeeded: it could have created a functioning democratic government with a strong US-equipped Iraqi military force. This would be an incredibly powerful, likely pro-western state, right on Iran’s border. The potential for a second, more destructive Iran-Iraq war existed, at least in the long-term. At best, the United States would completely fail: the Iraqi government would either simply collapse or be so corrupt and inefficient as to not matter anyway. The resulting chaos would threaten Iran’s security. No state likes it when their neighbor is in the throes of a deadly civil war; refugees and armed rebel groups both have their own unique security challenges. Not to mention Iran had already been dealing with this exact issue on their eastern border with the Taliban.

Even before the US military invaded, Iran had started preparing to confront American forces. Up to that point, the Iranian Quds force had already been sheltering various Iraqi Shiite resistance groups in Iran, the largest of which was the Badr Corps. Iran also hedged their bets by backing another new Shiite militia, the Mahdi Army, led by Moqtada al-Sadr. One of the ways Iran militarily supported these groups was by providing training in Iran, often in conjunction with Hezbollah. Groups of new recruits, brought together into a cohesive unit called a Special Group, would learn how to use explosives and conduct intelligence, sniper, and kidnapping operations. According to Dr. Michael Knights at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, these groups focused on anti-US operations, directing mortar and rocket attacks against US bases and using advanced improvised explosive devices (IEDs) with explosively formed penetrators (EFPs) to blow up coalition vehicles. Special Groups were also involved in planning and executing assassinations against key Iraqi leaders. In today’s Iraq, these special groups continue to exist and operate. As asserted in Knights’ report, “If Iraqi government policy crosses any ‘red lines’ (such as long-term US military presence in Iraq, rapid rearmament or anti-Iranian oil policy), the Special Groups could be turned against the Iraqi state in service of Iranian interests, showering the government center with rockets or assassinating key individuals.”

These Special Groups have allowed Iran to accomplish its security goals by preventing nationalist forces within the Iraqi state from fully developing, thus preventing the Iraqi state’s total resurgence. However, Iran is also attempting to gain influence through the legitimate Iraqi political process. The Shiite militiamen that participated in the Mahdi Army and Badr Corps now make up a large part of the Iraqi security forces, and leaders of those organizations, such as Moqtada Al-Sadr, have turned their resistance against US forces and protection of Shiite communities into political capital. Further, Iran has repeatedly attempted to unite Shiite Iraqis (roughly 60 percent of the population) into one cohesive political party, and while this might difficult to achieve, success would mean Iran would have incredible influence in the Iraqi political process. Essentially, it would turn Iraq into an ally, if not a vassal, of Iran, although it remains to be seen how this strategy turns out.

This dual strategy is also appearing in, of all places, Afghanistan, where Iranian weapons have been discovered and, in 2010, NATO forces captured a Quds force operative. Further, the US military has attributed the influx of EFPs, money, and other advanced weapons systems in Afghanistan to Tehran, although they point out that the support has been measured. That Iran would even provide support to the Taliban is puzzling, given their less-than-amicable history. The most obvious reason for their support would be to bog down NATO forces, with the natural result being a faltering and ineffective Afghan state. The US policy of regime change is certainly a threat to Tehran, and limiting NATO influence in the country would help assure the survival of the regime. On the other hand, a failed Afghan state means the resurgence of the Taliban, a dangerous situation for Iran. The key to understanding this paradox, according Dr. Sajjan Gohel, Director for International Security at the Asia-Pacific Foundation, is looking at Iranian investment in Afghanistan. Tehran has put significant sums of money in one particular Afghan province, Herat. Today, it is one of the more stable and economically booming places in the country, precisely because of Iranian investment in infrastructure projects such as roads, bridges, power generation, and telecommunications. It is becoming an integral part of Iran’s economy, and Stephen Carter at the Gregg Center for the Study of War and Society posits it may even be necessary for a future natural gas pipeline connecting Iran to countries such as Pakistan and India. Because Afghanistan does not have a majority Shiite population, the risks to Iran of it becoming a collapsed state are far greater. The return of Sunni militants may become as much a threat for Tehran as for the United States, but this consideration has only resulted in limiting Iranian support for the Taliban, rather than eliminating it. Carter points out that Iran’s measured support is intended as a warning: Iran perceives the possibility of strikes on its nuclear facilities to be a very real threat. Their networking with the Taliban might be intended to cultivate an ability to strike back at the United States in case of such an attack, thus making the costs the United States stands to receive too high to warrant a strike.

This may also be the reason why Iran has cultivated an ambiguous relationship with Al-Qaeda. Seth Jones, a senior political scientist at RAND, points out that following the US invasion of Afghanistan, Quds force transported several hundred Al-Qaeda-linked individuals into Iran. These operatives set up a “management” council with clear ties to Bin Laden, but in 2003, Tehran detained all of these individuals. In 2009 and 2010, it eased its control over them, but it has adhered to strict red lines, forcing the operatives to keep a low profile. Like the Taliban, Al-Qaeda is a strange bedfellow for Iran; indeed, many in the organization “revile” the ayatollahs. Still, Jones argues that there are two very good reasons why Iran is pursuing this policy. First, the detained operatives act as hostages, preventing terrorist attacks on Iran. Second, as with the Taliban, they afford Iran a way to strike back at the United States through terrorist attacks, in response to a strike on its nuclear facilities. This would be a very dangerous proposition, because a successful and deadly Al-Qaeda strike, especially on US civilians, traced back to Iranian support, would result in an even heavier US retaliation. Iran is playing a very dangerous game in supporting both the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, but Bruce Riedel at Brookings suggests that, despite this, “Tehran may consider the price worth paying in the face of Western aggression against its nuclear program.” Of course, the idea is to make the costs of a first strike so high that it never happens. US strategic planners would have to weigh the potential blowback from the Taliban and Al-Qaeda that such a strike would bring.

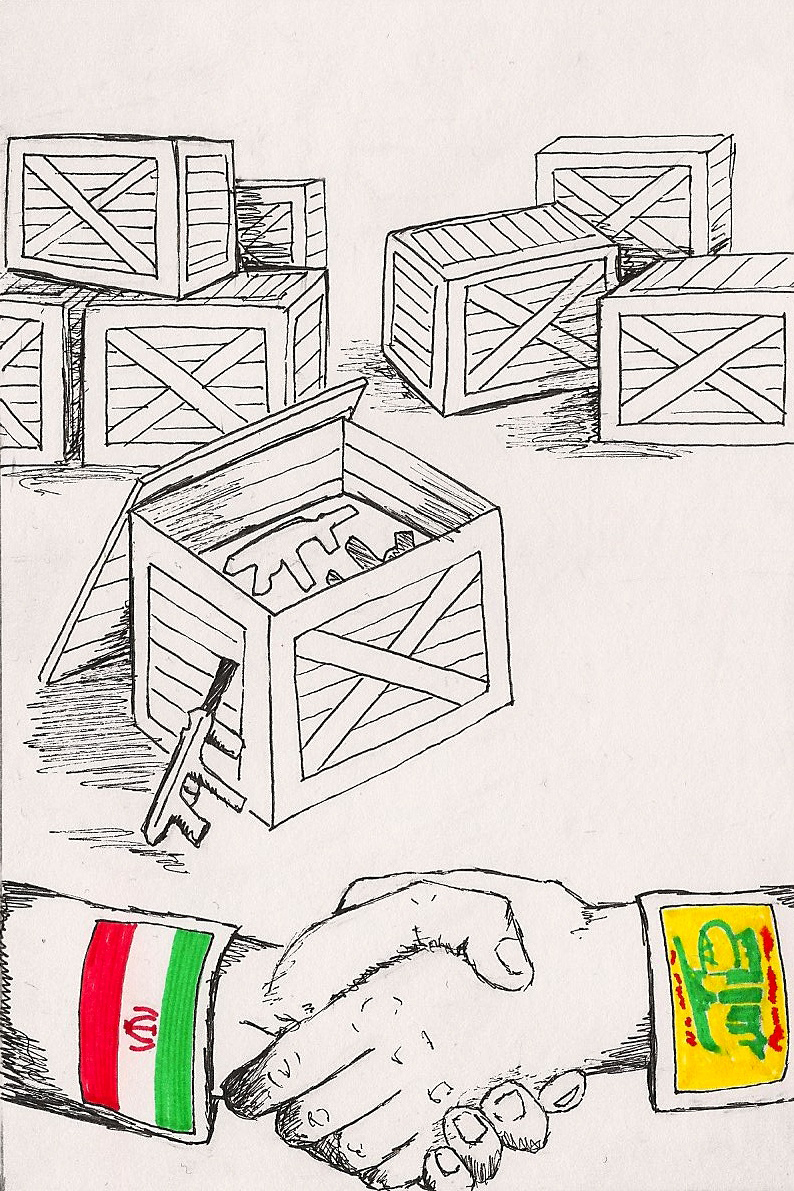

The United States is not, however, the only “Satan” that Iran must face. On the other side of the Middle East lies the ayatollahs’ other arch-nemesis: Israel. Since Iran has no border with Israel, to keep itself relevant in the Arab-Israeli conflict and continue to stoke the flames, it has to rely on its proxies, namely Hezbollah, Hamas, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Hezbollah is perhaps a textbook case of how Iran operates with various nonstate actors to extend its influence. Formed three years after the revolution that ousted the Shah, it continues to receive significant financial, organizational, and military support from Iran. This has made Hezbollah a potent military threat to Israel, which bloodied their nose in the 2006 war. The American Enterprise Institute reports that Iran has supplied Hezbollah with over ten thousand ground-attack rockets and missiles, as well as advanced anti-aircraft, anti-ship, and anti-armor missiles, and the training to use them. These weapons are all designed to counter the military power of Israel and neutralize its ability to operate in Lebanon. Further, in the Gaza Strip, Iran has recently begun providing these same weapons, albeit in smaller numbers, to Hamas and to Palestinian Islamic Jihad in the West Bank. By diversifying the number of anti-Israel militant groups it is funding, Iran is increasing its capability to continually strike at or distract Israel, and tangentially the United States, “without having to sacrifice the same proxy continuously.”

Towards that end, Iran also currently supports the embattled Assad regime. Syria is not only a longtime ally of Iran; it is currently its only state ally in the region. Losing Assad means losing a key friend, but it also means losing the ability to funnel weapons to Lebanon and Palestine. The Iraqi government has refused to stop Iranian cargo flights, likely carrying significant quantities of weapons, to Syria. The killing of a Quds force commander in Syria also shows their direct presence on the ground, to which Iran fully admits on the basis that they are there in an advisory role. In addition to advising and equipping Syrian military forces, it is likely that they are doing the same to pro-Assad paramilitary forces, specifically the Shabiha militias. As has become Quds force doctrine, they seem to be spreading their resources rather than putting all of their eggs in one basket. Losing influence in Syria is too devastating a loss for Iran.

When considering the broader issue of Iran’s rise to power in the region, and Western responses to it, the activities of the Quds force may be as significant, if not more so, as Iran’s nuclear program. The list of groups and countries with ties to Iran is significant and diverse: Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Hamas, Hezbollah, Assad’s government, various Iraqi insurgents, the Taliban, and even Al-Qaeda. They form the core of a shadow war Tehran wages against the West, and it is a war that has only been escalating, with dangerous implications for the United States and Israel. Iranian EFPs have killed American troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Iranian rockets and missiles continue to pose a deadly threat for Israel. Should Washington consider a policy of containment toward Iran, it is important to consider the ability of Iran to strike back via these proxy groups. As long as Iran exists with serious national security concerns, it will continue to fund these groups, and as long as that continues these groups will pose a significant threat to the United States. Iran’s operations stem from their sense of insecurity, and this leaves open the diplomatic option of a more conciliatory foreign policy toward Iran. Yet, the most placating and appeasing foreign policy on Washington’s part will not resolve the very real security challenges Tehran faces with regard to Iraq and Afghanistan, nor will it ameliorate relations between Iran and Israel and Iran and Saudi Arabia. While US actions may have started this shadow war, it is doubtful any diplomatic policy will bring a quick resolution.