Classroots Activism

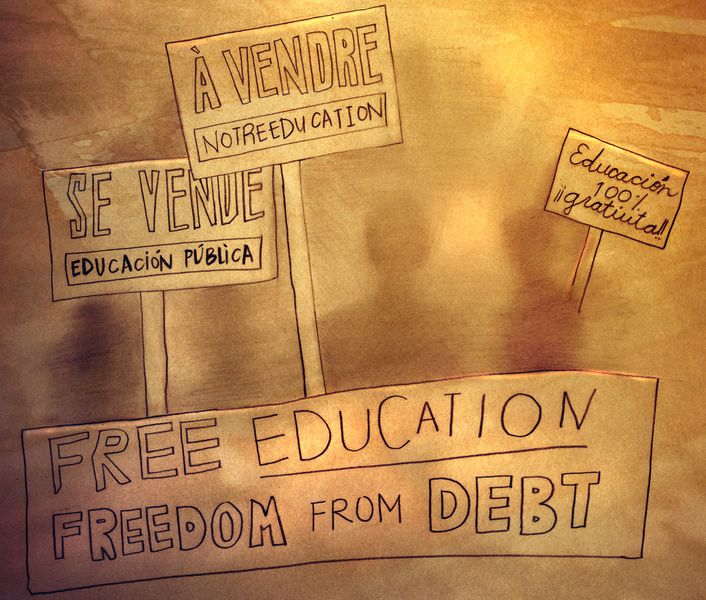

Brian Jones has a lot to be excited about. A New York City public school teacher deeply involved in grassroots organizing, he sees a growing radical vision among his fellow activists. “More and more parents and teachers are beginning to understand that it’s not about this policy or that, but really an all-out war over public education,” he explains. In the past several years, there have been numerous flare-ups of protest activity centered on equal access to quality public schools, from Chile to Québec to Chicago. Jones believes that recent shifts in the political landscape, along with enhanced potential for collaboration between organizations, signal that activists are on the verge of a transformational movement for public education.

Brian Jones has a lot to be excited about. A New York City public school teacher deeply involved in grassroots organizing, he sees a growing radical vision among his fellow activists. “More and more parents and teachers are beginning to understand that it’s not about this policy or that, but really an all-out war over public education,” he explains. In the past several years, there have been numerous flare-ups of protest activity centered on equal access to quality public schools, from Chile to Québec to Chicago. Jones believes that recent shifts in the political landscape, along with enhanced potential for collaboration between organizations, signal that activists are on the verge of a transformational movement for public education.

Jones and his fellow activists are engaged in resisting what he and many others refer to as “corporate education reform,” a set of proposals for America’s schools that many mainstream politicians, business leaders, and philanthropists have favored for several decades. These include using standardized tests as a major determinant of teacher compensation, closing schools whose students fail to meet certain benchmarks, and opening charter schools as alternatives to public schools. While the aim of such policies is to increase accountability and quality, critics believe they reflect the logic of profit-seeking businesses rather than that of educators, and that they are detrimental to fostering effective learning environments.

In New York, Jones is active in a variety of organizations, such as the Grassroots Education Movement, that seek to resist the implementation of these reforms. Their tactics include picketing at public schools forced to co-locate with charters, disrupting hearings on school closings, and staging protests outside of the New York City Department of Education. Increasingly, activists like Jones in cities all around the country are communicating and collaborating with each other to resist what they feel is a dangerous trend in education policy. In its place, they demand adequate funding and support for low-income schools, which would allow them to provide the same benefits as wealthy private and public schools, including small class sizes, experienced teachers, and rich curricula.

“Corporate” education reform policies were first enacted by the Department of Education during the Reagan administration. Back then, US schools were already vastly unequal, largely as a result of economic and ethnic segregation. Then, as now, a child’s zip code more or less determined the quality of his or her education. Officials believed that introducing competition would produce incentives for teachers and administrators to provide quality schooling. In the decades that followed, however, as subsequent presidents, mayors, and a cadre of wealthy philanthropists continued to make these reforms official policy, the effect was to exacerbate inequality. Many credible studies of educational research—conducted by institutions including the National Center for Performance Initiatives, the Institute for Education Sciences, and Stanford University—have called into serious doubt claims in favor of merit-pay for teachers, standardized testing as a holistic measure of academic learning, and charter schools as improvements on the model of traditional public schools. Whereas private schools and wealthy public districts have not been subjected to such policies, poor urban communities across the country have felt their disruptive effects while reaping little benefit, as these studies show.

Though today, corporate education reform is still the prevailing school of thought in official policy, it appears that the tide may be turning against it. Historically, teachers and students have both played major roles in popular protest movements, but until recently, there have been few notable cases of resistance to business-inspired practices in public education. Part of what makes people like Brian Jones optimistic, however, is the political transformation that has taken place due to the rise of Occupy Wall Street. For activists everywhere, Jones explains, Occupy represented a “huge injection of confidence in the public sphere. Our fight took on a vision of how people should be educated and provided for in our society.” What Jones sees in his fellow grassroots organizers is an enhanced consciousness of not only their power to support or oppose particular reform policies, but to manifest broader demands for an education system modeled on equality, rather than competition or other free-market principles.

For education activists, Occupy helped bring to light the connection between corporate education reform and greater economic structures of inequality. After all, Occupy was not just any revival of radical grassroots protest, but a manifestation of discontent with neoliberal ideology and policy. Neoliberalism refers to the belief, prevalent in policymaking since the 1970s, that the free market is the ideal organizing principle of society. The past three decades of neoliberal governance—characterized by a withdrawal of funds from public resources, hostility to organized labor, increased prominence of the financial sector and overall economic instability—have resulted in the economic and political inequality that gave rise to the discontent behind the Occupy movement. A direct result of Occupy Wall Street was to return issues of economic inequality to the political discussion, and into the consciousness of ordinary citizens. For more and more Americans, the connection between personal hardships during the Great Recession and historical trends in neoliberal governance has become much more salient.

Cuts to public education funding, as well as increased hostility to teachers’ unions, are textbook cases of neoliberal policy. Today, for parents and communities feeling the squeeze of corporate education reform, the relation to larger policy trends is increasingly clear. For many, the fact that a large number of prominent corporate reform advocates are among the country’s richest citizens is evidence that their policies do not represent the interests of the 99 percent. As the research of writer Joanne Barkan illustrates, corporate executives and billionaire philanthropists exercise a considerable amount of influence in the politics of school reform. Private foundations, for example, often have direct say over issues of policy. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan cites a Gates Foundation guide to school restructuring as his personal policy “bible” and a major influence on the Obama administration’s “Race to the Top” school reform legislation. According to activists, the disproportionate power that private, unelected individuals hold over education policy is indicative of an anti-democratic reform project based on corporate logic.

Occupy Wall Street, by identifying neoliberalism as a cause of inequality and reinvigorating grassroots movements, has helped to renew education activists’ ability to successfully organize. Nowhere has this transformation been more apparent than in last year’s teacher strike in Chicago. Although the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) is technically barred by law from striking over any issues other than salary, benefits, and procedures, President Karen Lewis insists that the goal of the strike went beyond mere contractual disputes. Teachers' unions, Lewis said in an interview with Democracy Now, have for too long been complicit in maintaining educational inequity. Critics often paint teachers' unions as top-down, bureaucratic institutions, an assertion that is not without truth. In the past, these unions have limited much of their activity to defending contract measures, leading them too often to close ranks rather than stand up for educational best practices. Although this was a logical approach to take in the midst of a policy regime of widespread cuts to teacher pay and deteriorating working conditions, it ultimately proved to be politically debilitating.

In Chicago, however, something had clearly changed. September’s strike was galvanized by a particularly radical wing of the CTU, known as the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (CORE). These teachers understood that their political goal was not only to have a fair contract with the city, but also to lead a popular struggle for equal education. Hence the mantra of the striking teachers: “Our working conditions are students’ learning conditions.” In a city that has been at the forefront of corporate education reform under Mayor Rahm Emanuel and former Chicago Public Schools CEO Arne Duncan, CORE members pulled no punches. Mass protests, in addition to the strike, were aimed explicitly at policies labeled as no less than “educational apartheid.” As a result of this renewed militancy, the strike demonstrated a nearly unprecedented degree of democratic union organizing, with rank-and-file teachers leading the charge rather than their bosses.

Community support for the striking Chicago teachers reveals an enhanced public consciousness of the connection between neoliberalism and education policy. The strike’s focus on corporate reform as a part of a neoliberal system of inequality, rather than on mere contract measures, created an almost immediate boost to the strike’s approval ratings. According to most polls, a majority of Chicagoans supported the strike, including over 66 percent of parents with children in public schools. Parent and teacher protesters together bore signs and banners that read not only “Support our schools,” and “Children first,” but also “Stop corporate greed,” and “Fund books, not banks.”

What’s more, communities affected by these policies feel empowered to oppose them. For those in power in Chicago, this overwhelming community rejection of neoliberal corporate reform came as something of a shock, and though the immediate results of the strike were mixed, grassroots organizers made clear gains in political leverage. The effects of the Chicago strike were not lost on teachers around the country. A new organization of New York teachers—calling themselves, in an explicit reference to CORE, the Movement of Rank and File Educators—are seeking to emulate CORE's takeover of union institutions. Additionally, teachers in Seattle recently staged a highly publicized boycott of city-mandated standardized tests. Teachers across the country, drawing inspiration from their Chicago counterparts, are communicating directly amongst themselves about strategies to oppose corporate education reform.

The growing wave of radical grassroots activism since Occupy Wall Street has demonstrated the potential of students, teachers, and parents as political agents. Perhaps equally as salient an issue for ordinary Americans as neoliberal K-12 reforms, however, is the defunding of higher education and the increased student debt that has accompanied it. It is well known that university tuition has climbed much faster than inflation over the past three decades. Even state colleges and universities that were once tuition-free, such as the University of California system, have increased tuition and fees at rates comparable to those of private and for-profit institutions. The result of these tuition hikes in higher education has been an unprecedented level of indebtedness.

As any visit to the now famous “We Are the 99%” Tumblr page can confirm, student debt has been one of the most common frustrations fueling Occupy Wall Street. Occupy has helped form a sense of class consciousness among many recent college graduates struggling to find work and pay off their loans. Some of the most prominent initiatives to come out of Occupy, for example, have been focused on opposition to student indebtedness and the de-funding of higher education, such as the “Strike Debt” coalition of debt resisters and the various “National Day of Action to Defend Education” protests across the country.

In the wake of Occupy Wall Street, more and more activists are beginning to realize that both corporate education reform and the troubles in higher education – de-funding and indebtedness – share a common root in neoliberal policy. If grassroots movements today can successfully highlight and resist the historical trends that have shaped both K-12 and higher education, there is potential to transform not only public education, but also the larger political and economic structures of American society as well. Such transformational movements have already begun both in Québec and Chile, and both provide vital lessons for activists in the United States.

University students in the Canadian province of Québec, home to a long tradition of syndicalist student organization, were successful in staging a massive strike that not only overturned a proposed tuition hike for public universities, but also led to the defeat of Québec's Liberal government in last September's elections. A crucial strength of the Canadian student movement has been an understanding of its mission not only as an education struggle, but also as a class struggle. CLASSE, a leading student union, consistently referred to its activity as a “social strike,” and from the beginning, the movement sought to transcend students’ immediate interests. Students formed alliances with mining and public sector workers facing layoffs and pay cuts; their participation in the protests was crucial to movement’s base of support.

For American activists seeking inspiration, the Canadian strike illustrates that cooperation between students and labor is politically viable. Though American students lack Québec's history of militant student organizing, teachers’ union institutions may be able to provide organizational support for a mass movement. In fact, the social justice unionism of CORE in Chicago and MORE in New York is an optimistic sign of unions’ ability to be a progressive force. With a growing consciousness of the connections between school and labor policy under neoliberalism, there is potential to translate their militancy into the sphere of higher education, perhaps by forming alliances with disaffected adjunct faculty members or by reinvigorating student unions. It will be no small task to rebuild these organizational structures in American universities, but by no means impossible, and almost certainly necessary to form a radical movement for educational equality.

Protests in Chile have demonstrated how such a movement for transformational education reform can become a force for broader social change. As a result of a neoliberal education system left over from the rule of former dictator Augusto Pinochet, Chile’s public schools, at all levels, are the most privatized and unequal among rich countries. Tuition for primary, secondary, and tertiary education alike is often prohibitively high for most Chileans. A defining feature of the ongoing mass protests across the country is that unlike Québec, where protests began as a defensive response to proposed tuition hikes, Chileans are on the offensive to demand a radically transformed education system, fundamentally altering the scope of what the protests can accomplish. In an interview with The Guardian, Camila Vallejo, the movement’s unofficial spokeswoman, maintains quite explicitly that while the protesters’ immediate goal is universal free education, their struggle is ultimately about overthrowing the neoliberalism that was violently imposed by Pinochet. American activists have the potential to follow the Chilean example and turn defensive struggles—against school closures or university budget cuts, for example—into an offensive movement not only for a more equal education system, but also for a radically egalitarian society.

If grassroots activists in the United States can build a unified movement, learning from their counterparts in Québec and Chile, perhaps the debate over education reform will translate to broader challenges to the neoliberal social order. One of the most common assertions of corporate reformers is that it is not necessary to fix poverty in order to fix education. One may speculate that to successfully challenge this neoliberal logic in education would call into question other forms of thinking that prevent meaningful discussions of addressing poverty. Occupy Wall Street’s greatest success, however, was to put such a radical critique of economic and political systems back on the agenda, providing an outlet for public discontent with the neoliberal order. Education, as a system that represents several diverse yet interconnected consequences of neoliberal policy, presents itself as a strategic place to translate this critique into action. The pieces are in place to mobilize a mass movement for educational equality. The question today is not whether or not such action will take place, but merely where and when.

Correction: It was previously stated that Brian Jones is a teacher in East Harlem. Though currently on leave, he now teaches in Brooklyn.

Correction: Previously, the article read "last November's elections," and was changed to "last September's elections."