Mudslinging in Denial

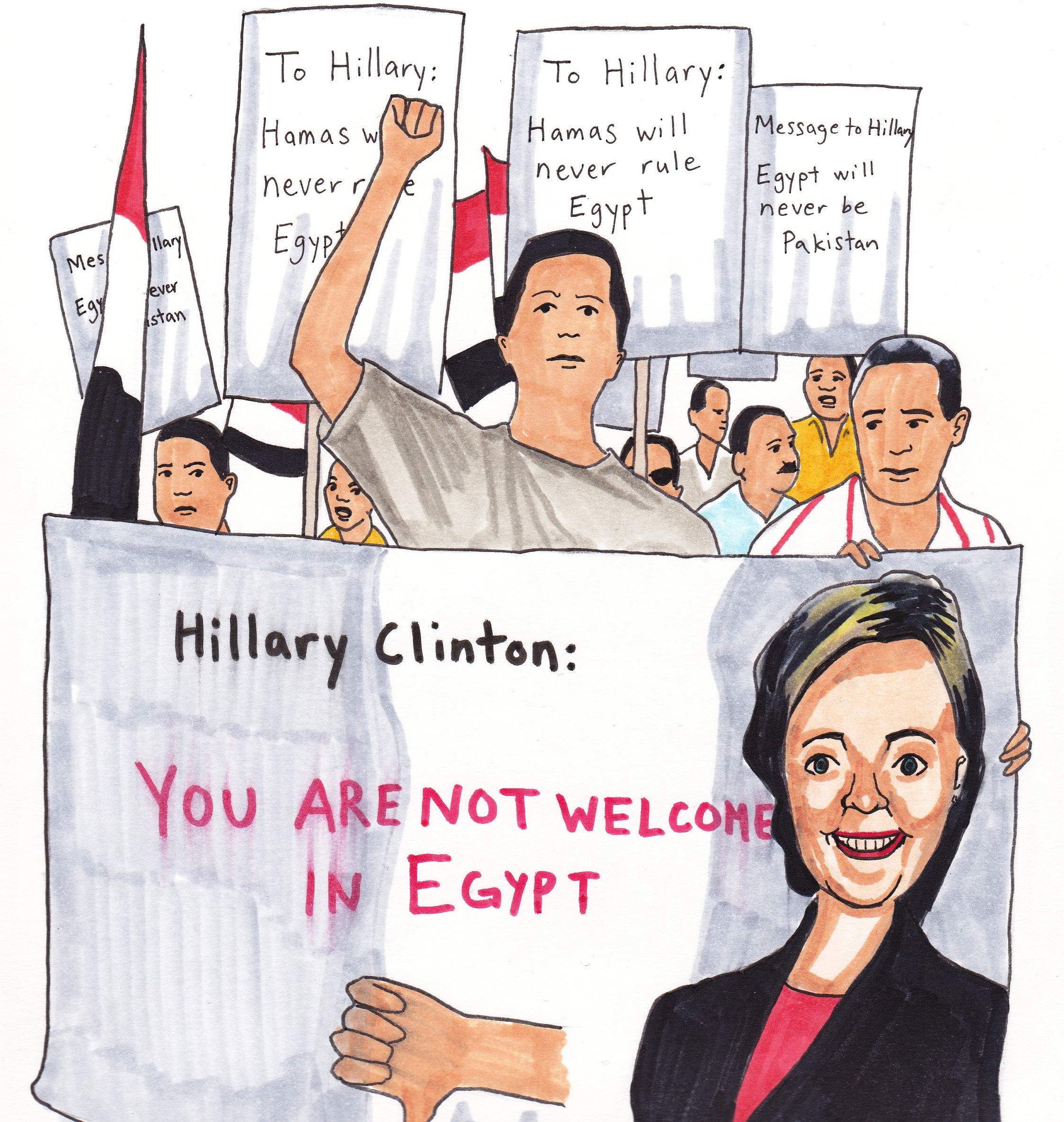

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has been accused of many things throughout her political career. Yet until her visit to Egypt this past July, being a “Secret Islamist” was not one of them. Pulling up to the Four Seasons in Cairo, however, Clinton encountered a number of surprising allegations. “Hillary Clinton is the Supreme Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood,” one sign read in the midst of screaming protesters. “Stop the U.S. Funding of the Muslim Brotherhood” another poster demanded, flanked by an even larger sign, saying, “To Hillary: Hamas Will Never Rule Egypt.” Arriving just weeks after Egypt’s first democratic elections, Clinton had no doubt expected some degree of protest during her visit. But as the Secretary’s trip progressed, it became increasingly apparent that the Clinton-Brotherhood rumor was not just an Egyptian phenomenon. Rather, this particular conspiracy theory was one with deep roots that traced back not only to the banks of the Nile but also to the distant shores of the Potomac.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has been accused of many things throughout her political career. Yet until her visit to Egypt this past July, being a “Secret Islamist” was not one of them. Pulling up to the Four Seasons in Cairo, however, Clinton encountered a number of surprising allegations. “Hillary Clinton is the Supreme Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood,” one sign read in the midst of screaming protesters. “Stop the U.S. Funding of the Muslim Brotherhood” another poster demanded, flanked by an even larger sign, saying, “To Hillary: Hamas Will Never Rule Egypt.” Arriving just weeks after Egypt’s first democratic elections, Clinton had no doubt expected some degree of protest during her visit. But as the Secretary’s trip progressed, it became increasingly apparent that the Clinton-Brotherhood rumor was not just an Egyptian phenomenon. Rather, this particular conspiracy theory was one with deep roots that traced back not only to the banks of the Nile but also to the distant shores of the Potomac.

On June 13, Congresswoman Michele Bachmann (R-MN) first expressed concern that the Muslim Brotherhood was covertly influencing the Department of State. In a letter submitted to Deputy Inspector General Harold Geisel, Bachmann, along with Representatives Trent Frank (R-AZ), Thomas Rooney (R-FL), Louie Gohmert (R-TX), and Lynn Westmoreland (R-GA) raised “serious questions about Department of State policies and activities that appear to be a result of influential operations conducted by organizations and individuals associated with the Muslim Brotherhood.” Citing “The Muslim Brotherhood in America: The Enemy Within,” a ten-part video series produced by Frank Gaffney, a former Assistant Secretary of Defense and the founder of the Center for Security Policy, Bachmann and her colleagues contended that “the State Department and, in several cases, the specific direction of the Secretary of State, have taken actions recently that have been enormously favorable to the Muslim Brotherhood and its interests.” Citing Gaffney, Bachmann and four other congressional representatives then specifically accused Clinton’s Deputy Chief of Staff, Huma Abedin, of having family ties to the Muslim Brotherhood and, due to Abedin’s “routine access to the Secretary and policy-making,” requested that Geisel launch a formal investigation to determine “the extent to which Muslim Brotherhood-tied individuals and entities have helped achieve the adoption of these State Department actions and policies, or are involved in their execution.” Though the letter goes on to detail other instances of Brotherhood-friendly policies, such as engaging the Muslim Brotherhood in dialogue or participating in Organization of Islamic Cooperation meetings, it provides no additional evidence to support its claims against Abedin, save for citing Gaffney’s video, which, among other things, claims that the Muslim Brotherhood has infiltrated past Republican and Democratic White House administrations and is destroying the United States from within through “civilization jihad.” Subsequently, with no credible evidence to back her claim, Bachmann’s accusations went unnoticed in American political circles.

One month later, however, anti-Clinton demonstrators were accusing the Secretary of establishing a covert American-Brotherhood partnership and orchestrating a Brotherhood takeover of the White House. What made their claims so significant, however, was that some of the protesters were citing American, not Egyptian, sources to back their claims. Outside the Four Seasons, Egyptian demonstrators quoted American blogs, think tanks, and videos, all warning against Muslim Brotherhood plots to infiltrate the White House. Egyptian bloggers like Sara Ahmed cited a web episode where Frank Gaffney and General William Boykin, a former Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence, repeated Gaffney’s allegations of Abedin’s connections to the Brotherhood. In a high level meeting with Christian Egyptian leaders, one invitee informed the Secretary that Abedin confirmed the existence of a secret Brotherhood plot, directly citing Bachmann’s letter. Though perhaps a bit delayed in its effect, it seems that Bachmann and her colleague’s allegations did, in fact, have some sort of impact after all.

Conspiracy theories have long played a prominent role in contemporary Egyptian politics. The Egyptian “rumor mill” is the legacy of autocratic regimes and decades of state-controlled media, and it has been cultivated and sustained by the perfect storm of historical forces, social conditions, and a strong state hand. Since Egypt gained its independence from Britain in 1952, Egyptian presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat, and Hosni Mubarak all used state-controlled media to entrench their own rule. Most recently, Mubarak manipulated and utilized public mood to two effects during his twenty-year reign. By fabricating and encouraging foreign conspiracy theories, Mubarak deflected criticism following domestic political failures and instead blamed foreign actors. Thus, by invoking external conspiracy theories to explain his own failures, Mubarak retained his control over Egypt in spite of his political and economic ineptitude.

At the same time, Mubarak exploited his country’s instability to justify his need for international support, particularly from the United States. Having maintained a cold yet unchallenged peace with Israel since he took office, Mubarak convincingly painted himself as the only barrier standing between continued peace and a Muslim Brotherhood takeover. In fact, as the Egyptian opposition gained steam leading up to the revolution’s January 25 start, many joked that any suggestion to Mubarak of stepping down was met only by the words “Muslim Brotherhood, Muslim Brotherhood, Muslim Brotherhood.” And for a long time, these “magic words” seemed to work; for decades, the United States provided significant military and economic aid to the Mubarak regime, turning a strategic blind eye to Mubarak’s harsh authoritarianism, disregard for human rights, and persecution of minorities. Moreover, having secured the United States’ military and economic support, Mubarak utilized this international backing to further justify claims of “foreign interference” in Egyptian domestic politics. So long as the United States continued to prop up the Mubarak regime, they seemingly validated Mubarak’s claims of an all-powerful American government capable of directing and molding Egyptian politics however it saw fit. Therefore, even once Mubarak was gone, Egyptians had long grown accustomed to looking for and expecting “foreign interference” as a possible explanation for their political problems.

Given the legacy of conspiracy theories under Mubarak, the effect of an alleged American policy switch in favor of the Muslim Brotherhood provided the Egyptian rumor mill with adequate material for Clinton’s visit, even independent of Bachmann’s contribution. For example, former Parliamentarian and prominent Coptic Christian leader Emad Gad claimed on the eve of Clinton’s visit that the United States had struck a deal with the Muslim Brotherhood in exchange for preserving peace with Israel. Specifically, Gad was quoted in Al Ahram, Egypt’s largest-circulating, state-owned newspaper, saying “In exchange for Morsi's being named president, the Brotherhood is expected to protect Israel's security by pressuring Hamas – the Brotherhood's branch in Palestine – not to launch military attacks against Israel, and even accept a peace agreement with Tel Aviv.” Youssef Sidhom, a prominent editor and participant in Clinton’s Christian leaders roundtable in Egypt, argues that the Clinton-Brotherhood conspiracy was in part rooted in the timing of American statements, which suddenly began to “bless democracy” as the Brotherhood’s victory prospects became apparent. After all, the United States had almost completely reversed its stance on the Muslim Brotherhood following former President Mubarak’s ousting in the Egyptian Revolution. For years, preventing an Islamist rise to power had been the raison d’être behind the support for Mubarak’s oppressive, anti-democratic regime. However, when Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi was announced as Egypt’s first democratically elected president in June 2012, the American government almost immediately embraced Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood without question, shocking many Christian, liberal, and secular groups within the Egyptian political sphere. Consequently, as Washington lauded the Brotherhood’s victory as a triumph for Egyptian democracy, many Brotherhood opponents began searching for explanations behind the United States’ significant policy reversal.

Despite the United States’ sudden policy switch regarding the Muslim Brotherhood, politics is not providing the only fuel for the rumor mill. Even after the revolution, private Egyptian media sources have continued exploiting conspiratorial narratives to boost viewership and popularity. One Egyptian media personality, Tawfik Okasha, has been particularly successful in this respect. Dubbed the “Glenn Beck of Egypt,” Okasha seems to come up with a new conspiracy theory every day amidst rambling political tirades and equal-opportunity diatribes against the United States, Islamists, and Israel. For example, Okasha claimed that the United States had rigged the presidential run-offs in favor of Morsi so that they could turn over Egypt’s oil fields to Israel. Although Okasha’s abrasive yet charismatic rhetoric is largely counterintuitive given longtime American support for Mubarak – the Brotherhood’s greatest enemy – and the complications that an Islamist government would likely bring to Egypt’s relationship with Israel, Okasha was instrumental in spreading Clinton-Brotherhood conspiracy theories and even in galvanizing anti-Clinton protests during her July visit. Protesters even adopted insults from Okasha’s popular show, “Egypt Today,” shouting “Monica, Monica!” at Clinton in both Cairo and Alexandria.

In light of Clinton’s visit, it would be foolish to assume that the Egyptian revolution created a political tabula rasa. By the time of the Egyptian Revolution, Egyptians were long accustomed to political narratives centered around foreign interference, constant attempts to stymie Egyptian success, and a direct American interest in directing Egypt’s internal affairs. Consequently, it came as no surprise that “No to Foreign Interference” was a common slogan during the presidential run-off in July, or that the United States was accused of election-rigging, seemingly irrespective of which candidate was projected to win. Furthermore, the diversity of Egyptian political actors only amplified supposed American interference in Egyptian domestic politics. Given that political discontent was already frequently redirected toward the United States by Egypt’s various authoritarian regimes, this base level of unhappiness will ensure a near-constant projection of blame on the United States irrespective of actual American interests.

The 2012 Egyptian presidential elections provide the perfect example of this process. When Morsi won the presidential run-off with 51.7 percent of the vote, vocal liberal, secular, and Coptic leaders rushed to decry “foreign interference” and American tampering with the election process. Yet had the scales tipped in favor of Ahmed Shafik, there is no doubt that the United States would have been met with identical objections, just from the mouths of Islamists and anti-Mubarak coalitions. Clinton’s meeting with Christians in Cairo was cast as American-sponsored sectarianism and attempts to unravel Egypt from the inside. Had Clinton not met with Christians, however, her actions would have confirmed growing suspicion among secular, liberal, and Christian coalitions that President Obama had “sold out” Egypt under the convenient guise of democracy. Though the summer’s most influential political rumor in Egypt traces back to rightwing political attacks against the Obama administration, the rumor mill acts independently of partisan divides. So long as discontent is transfigured into anti-American blame, the rumor mill can just as easily pick up comments from one side of the aisle as it can from the other.

Two years after the Egyptian revolution, it will take far more than ousting Mubarak from the presidential palace to undo decades of limiting freedom of the press, blaming foreign conspiracies, and fostering a media environment that continues to privilege sensationalism over objective reporting. After decades of oscillating press freedom, a constant narrative of foreign intervention, and the challenges of democratic growing pains, Egyptian conspiracy theories will remain alive and well into the foreseeable future. Though longstanding American support for Egyptian authoritarian regimes undoubtedly helped build and sustain this rumor-producing environment, blaming only the United States would be as myopic as the conspiracy theories themselves. The Egyptian rumor mill is an Egyptian problem that requires an Egyptian solution. It cannot, however, be solved overnight. So long as Egyptians turn to “foreign hands” as an explanation for their problems, this lack of critical self-reflection will only make it more difficult to accurately evaluate what Egypt needs in order to adequately address its many challenges going into the future. The Egyptian Revolution represents an inspiring and entirely unprecedented achievement for the Egyptian people. However, continuing to perpetuate the type of conspiratorial narratives imposed upon them by 60 years of authoritarian rule would do the revolution considerable injustice.

But the need for self-reflection does not stop there. Much like the wide-reaching impacts of American domestic politics, responsibility for a successful Egyptian transition also lies on this side of the Atlantic. Though there may be little that the United States can do now to change conditions on the ground in Egypt, American politicians cannot simply look at the Egyptian rumor mill and throw up their hands in defeat. The US government has learned that “politics no longer stops at the water’s edge” is not only a truism, but is becoming excessively cliché; American politicians and leaders must start taking more responsibility for what they say and do. Americans may be unable to confine the effects of domestic mudslinging to the American political game, but we can control the contents of the proverbial mud.

During Egypt’s uncertain political transition, American sources also claiming a Clinton-Brotherhood plot only exacerbated strained American-Egyptian diplomatic ties. Bachmann and her colleagues’ claims further alienated Egypt’s Christian community, which already feels more marginalized and vulnerable after Morsi’s victory. So long as the ridiculous narrative that Obama harbors a secret Islamist agenda remains, it will be difficult for American diplomats in Egypt to do their job, let alone anticipate the effects of the many unborn conspiracy theories still to come. Regardless of the role that the United States plays in Egyptian rumor production, American politicians across party lines have an obligation to choose their words wisely and consider their potential impact overseas. Therefore, as Egyptian democracy takes its first wobbly steps following the 2011 revolution, it is not just security issues, economic stagnation, or political growing pains that will undoubtedly throw a wrench into American-Egyptian relations. When any opinion is just a click away, the mudslinging inherent in American domestic politics has the ability to directly impact Egypt’s post-revolutionary transition, creating detrimental outcomes for Egyptians and Americans alike.