What Makes A Regime Legitimate?

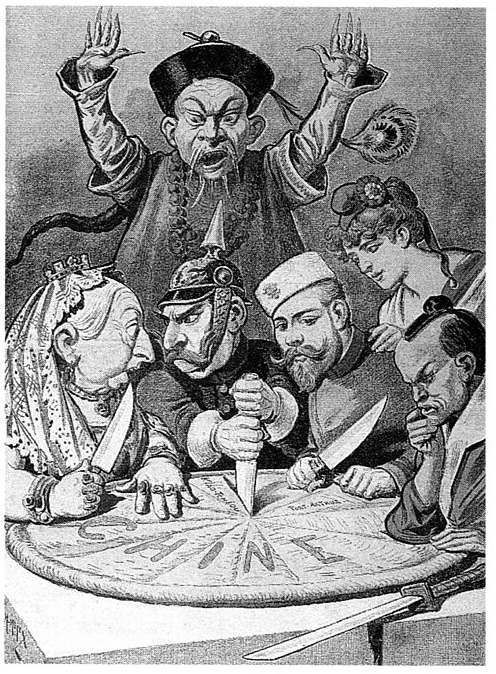

Last column, I wrote about the events in the Middle East as a sort of “grand game” between Israel and the United States against Iran. Recently, some commentators and writers have gone as far as to insinuate that what we are seeing is an attempt to destabilize and overthrow a regime that is, in some fashion, legitimate. Some, such as Pepe Escobar, have pointed to discrepancies between the official UN death tolls in Syria with the Arab League reports, as evidence of a (necessarily) vast conspiracy to influence world opinion. Other thinkers, like Joseph Massad, are less radical, but do insist upon the possibility and necessity of a “third choice” between “imperialism and fascism,” framing Western and Arab intervention as imperialism and dictatorial rulers as fascism.

Now, the instinctive opposition to imperialism in all forms and colors is unsurprising and understandable; after the legacy of colonialism throughout the world, I doubt that many people truly sympathetic to the populations of the Arab world would endorse imperialism as “good.” And it certainly would be foolish, as I wrote before, not to expect outside powers to attempt to press for their own interests. But to place the thuggish regimes of Assad, Qaddafi, and Mubarak next to international concerns about regime violence and the bloodshed that is verifiably happening in Syria, as Massad does, forces us to into making a choice that is not the third way. It is equivocacy, and it abets fascism.

Last column, I wrote about the events in the Middle East as a sort of “grand game” between Israel and the United States against Iran. Recently, some commentators and writers have gone as far as to insinuate that what we are seeing is an attempt to destabilize and overthrow a regime that is, in some fashion, legitimate. Some, such as Pepe Escobar, have pointed to discrepancies between the official UN death tolls in Syria with the Arab League reports, as evidence of a (necessarily) vast conspiracy to influence world opinion. Other thinkers, like Joseph Massad, are less radical, but do insist upon the possibility and necessity of a “third choice” between “imperialism and fascism,” framing Western and Arab intervention as imperialism and dictatorial rulers as fascism.

Now, the instinctive opposition to imperialism in all forms and colors is unsurprising and understandable; after the legacy of colonialism throughout the world, I doubt that many people truly sympathetic to the populations of the Arab world would endorse imperialism as “good.” And it certainly would be foolish, as I wrote before, not to expect outside powers to attempt to press for their own interests. But to place the thuggish regimes of Assad, Qaddafi, and Mubarak next to international concerns about regime violence and the bloodshed that is verifiably happening in Syria, as Massad does, forces us to into making a choice that is not the third way. It is equivocacy, and it abets fascism.

What is so worrying about thinkers like Massad and Escobar, as well as those that agree with them, is that the wise caution and questioning displayed towards motives and actions of Western countries immediately turns into distrust, reading of all actions by non-Arab actors and reflexive defense of regimes that are equally despicable compared to imperialists. Buying into the nonsense that these demonstrations and revolutions are external creations supports the regimes’ slaughter of their own people under the banner of “restoring order” and “stability;” more than that, it is a huge insult to the Syrian (and other revolutionary) people, who have given many lives and much struggle for the sake of overturning a minority regime that reserves the overwhelming positions of power and government for its own sect, allocates enormous wealth to the president’s family, tortures dissidents, and besieges restive cities. More than this, it represents a claim on what the limits of the “Arab” or “Syrian” or other national identity may include; this claim categorically and short-sightedly excludes any alignment or agreement with Western interests, and though not explicitly, seems to even forbid speech, demonstration, and revolution as a legitimate expression of dissent.

And this leads to the questions that one must ask: Why do so many seem inclined to defend these criminal regimes? Why does reflexive anti-imperialism seem to translate so often into the support of dictatorships, directly or otherwise? What makes a regime legitimate, insofar as legitimacy is reflexively defined as being seen as legitimate?

With each passing day more die in Homs, Hama, Deraa, and Daraya; yet the question is not if the regime will crumble and pass, but when, under how many deaths, and to what successor. If democracy or anything resembling it is to take hold, the people of Syria – along with the intellectuals, thinkers, and policymakers in the rest of the world – must not fall prey to reflexive reactionary-ism, and instead follow their course with dignity and respect.