Two Months Later

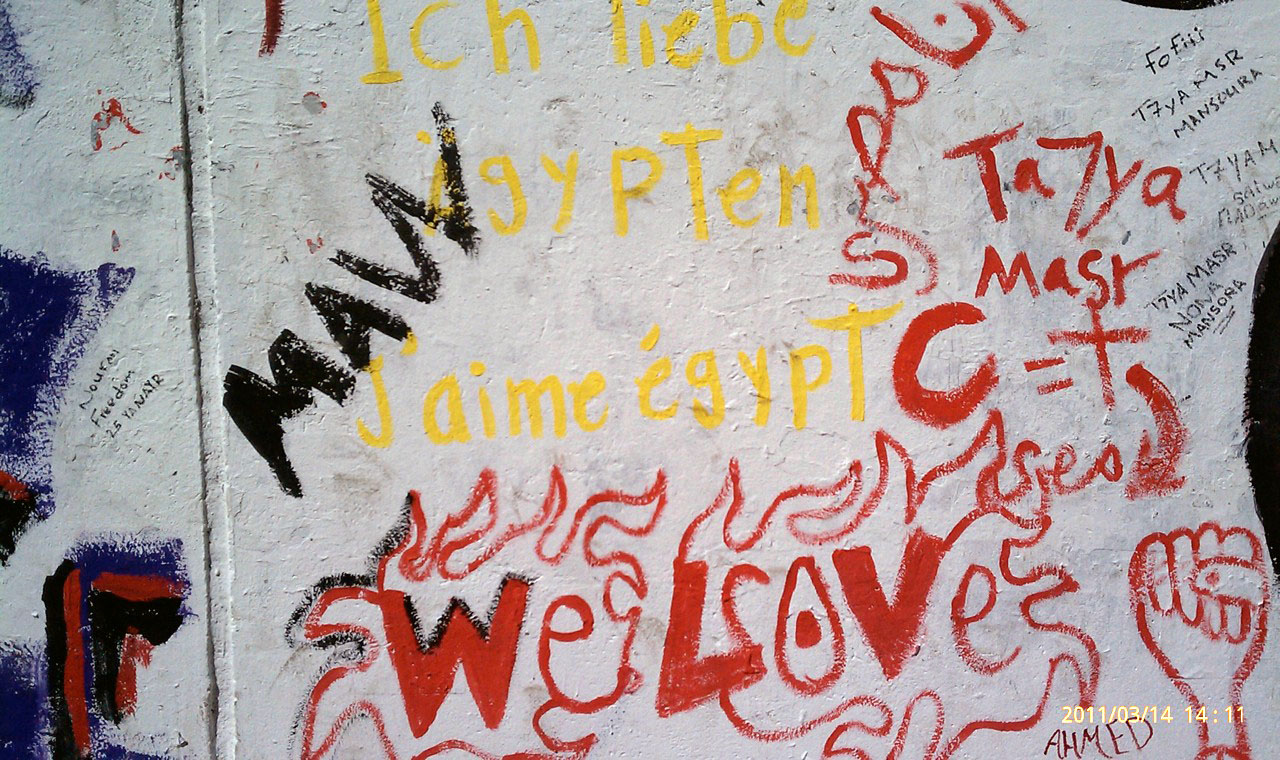

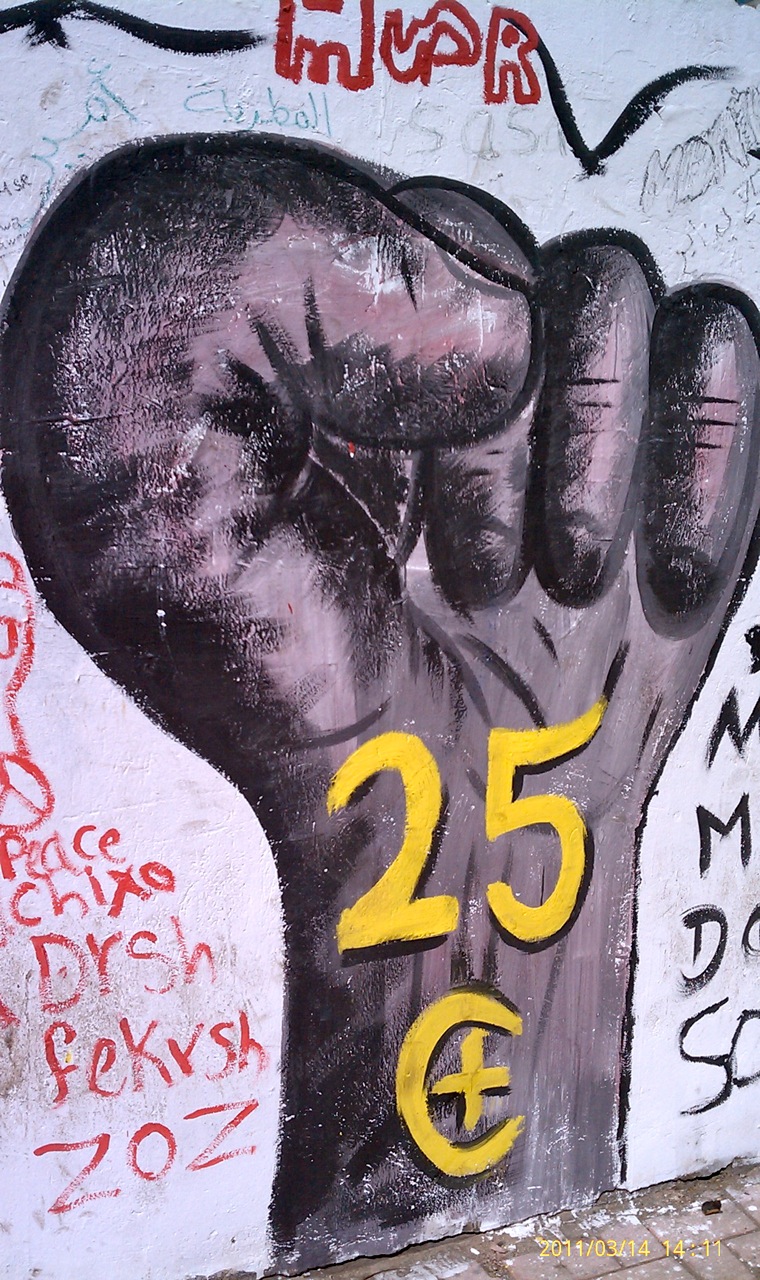

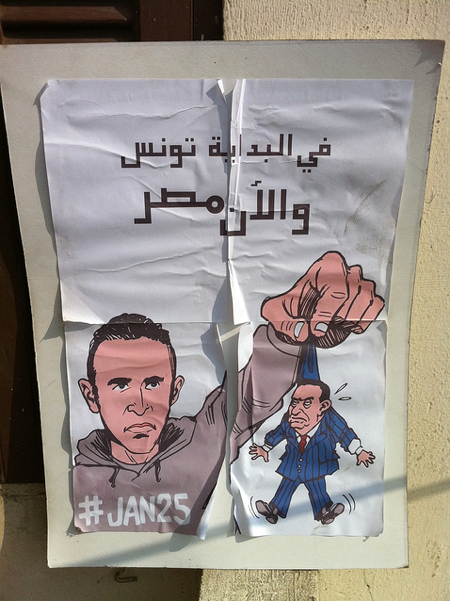

The pyramids are the only Wonder of the Ancient World still standing. For most people, they are an exotic symbol of Egypt and the ancient mythos the name of that nation conjures up—the embellished and aggrandized tales of curses, ancient gods, slavery and hidden treasure that captivate children the world over. But when I visited Egypt in March, I did not see the pyramids—not even from a distance. I was more captivated by the mysteries of the very recent past. I spent two weeks wandering around Tahrir Square in Cairo, the center of the Jasmine Revolution, warding off hibiscus salesmen and increasingly desperate pyramid tour guides. Tahrir is the Arabic word for “freedom,” and fittingly tangible signs of the recent political transformation were everywhere. I was in Egypt only one month after Mubarak stepped down from his thirty-year run as president, and I had the sense that the streets of Cairo were full of hope and pride. Revolutionary graffiti completely covered the walls around the main square. Tags included, “unity for Egypt,” “freedom,” “democracy,” “fuck Mubarak” and “Facebook!” underneath the symbols of the Coptic cross and the Muslim star and crescent. The sun-faded 1960s cars that are common in Egypt sported fresh “JAN25” bumper stickers.

Egyptian flags were also ubiquitous. Not only were there physical cloth and paper flags hanging on buildings, but people had painted everything from trashcans to trees in the national colors—red, white and black. I went to visit a friend for dinner in Cairo and we admired the view of the city from his rooftop—old, crumbling stone homes with silhouettes of laundry lines and a sea of satellite dishes. On the neighboring roof there were children practicing what is known as “pigeon flipping.” They used a series of pigeon calls and coos and skillfully twirled and waved an Egyptian flag as a net, in hopes of enticing birds to cook and eat.

I soon realized that my initial feelings of hopefulness for Egypt’s political situation were only based on cursory observations as an American divorced from the recent events. After a week in Cairo, I became more sensitive to underlying tensions.

On closer observation, the atmosphere began to feel like New York in the months following the attacks of September 11, 2001—a volatile mix of misguided pride and fear. It seems that many Egyptians were not caught up in a tide of nationalism but were merely struggling to carry on with daily life. During the revolution, the stone tiles that had once made up the sidewalks of Tahrir Square had been violently torn from their bases to serve as makeshift ammunition against pro-regime thugs. The walkways are now sand and have turned a red-gray hue from the heavy foot traffic. There are still tanks with armed soldiers guarding the city, serving as check points at night for the city-wide curfew which changes on a daily basis. It is not uncommon to find the square drenched from last night’s water cannon riot control. There are still protests. I witnessed people climbing trees and street lights, waving giant flags and chanting demands to their toppled government. The message behind these protests was unclear—some Egyptians said they were protesting for “faster internet” and others told me they just wanted “change.”

I never felt unsafe at any point during my trip. However, I did feel unnerved when a hibiscus salesman in a local market called me an “American spy” and started following me down the street after I politely declined to enter his shop. It is no secret that street vendors in the Middle East can be aggressive in their attempts to bait foreign tourists into their stores, using an armory of calls and tricks (not unlike the children who tried to “flip” pigeons with their Egyptian flags). But since the revolution, Egypt’s tourism industry has plummeted by over 25 percent and will not recover for some time, leaving the usually mildly aggressive salesmen even more on the edge.

The immediate area around Tahrir Square is slowly being rebuilt. McDonald’s was among the first restaurants to reopen, and a Hardee’s is on its way. I hear that the national museum will also soon reopen—when I was there it was just a parking lot for bombed-out cars with a snack stop for soldiers in tanks. Since my return home, there have been reports of more violence and deaths in Tahrir. The impatience of the people, who helped spark one of the world’s fastest revolutions, is unyielding. I want to have great hope for Egypt, and part of me truly does, but based on what I’ve observed, it will be a long road to the next election scheduled for September.