Borderline Dysfunctional

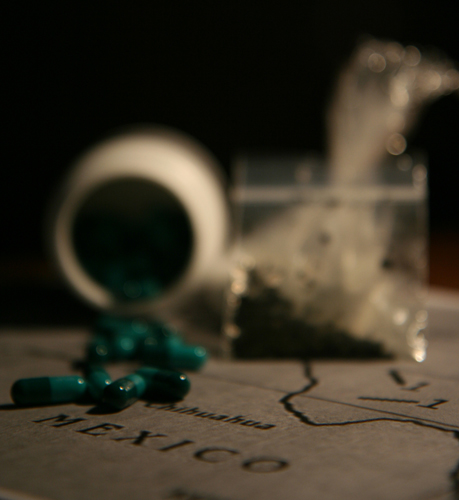

Picture a world where the whistle of bullets drowns out the chirping of birds. Where army units patrol violent, poverty-stricken streets. Where farmers walk among fields of poppy, hoping a successful harvest will provide for their families. Where mothers of lost sons gather and pray that each new day may bring a resurrection of peace. This is not a distant snapshot, but a reality close to home. Welcome to the world of narcocultura. Welcome to Mexico. Stretched across the Mexican landscape is a complex and diverse tapestry of rival drug lords and organizations pitched in constant war over drugs and profits. For decades, these cartels served as a middleman for the international illicit drug market because of Mexico’s strategic position along the porous American border. There efforts were regional and their targeted killings largely limited to rival gangs. But in the past decade, the numbers of targeted civilians and government officials have increased. In the past four years alone, Mexico has witnessed over 18,000 drug-related deaths, many beheaded or showing signs of torture.

One of the main causes behind the noticeable shift in cartel activity is the recent development in the relationship between the lords and the government. Before and during the 1990s, a silent “pact” existed between the lords and the government, in which interference between the two was kept to an agreed minimum. The cartels limited their activity to drug trafficking and murder attempts to rival gang members, and public officials would only arrest low-ranking members and intercept small quantities of drugs. In return, many of the drug profits were often reinvested in local communities in the form of schools, churches and employment opportunities. This fragile relationship, however, only works under a one-party system. When the 70-year monopoly of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) ended with the election of President Vicente Fox in 2000, the cartels encountered a weaker central government and subsequently began to overstep the limits of their activities. In addition, with the decreased power of the Cali and Medellin cocaine cartels in Colombia in the ’80s and ’90s, Mexico’s cartels used the advantage of their strategic position on the U.S. border to rise to preeminence in the international drug market.

Seeking to crack down on violence and corruption, and possibly to reverse public perceptions of weak leadership following a close election, President Felipe Calderón, on just his tenth day in office, took the unprecedented step in December 2006 of deploying 36,000 federal troops to nine states. The strategy sought to decrease the amount of drugs crossing the border, capture high-profile leaders, and seize shipments and destroy illegal cultivation.

Almost four years of fighting, 45,000 troops, and countless innocent victims later, Calderón has yet to succeed in meeting his primary goal of increasing overall public security. With over 2,000 recorded deaths, 2010 is quickly on its way to surpassing the previous high of 5,580 set in 2009. With few results, ordinary citizens are beginning to turn against the government’s efforts. In a March poll, 59 percent of Mexico’s population believed the cartels were winning the war, in contrast to 21 percent who supported government’s methods.

This connection between violence and troop deployment can be understood as one of increased competition amongst Mexico’s gangs for scarcer territory and resources, as astutely pointed out by Viridiana Rios, a doctoral fellow at the Harvard Inequality & Social Policy Program. As the Mexican Army began to clamp down on supplies and trafficking routes, the cartels saw a dip in profits and more of an incentive to use violence against their rivals. When the troops decreased the number of traditional trafficking routes into U.S. markets, the dealers were forced to fight for those passages that still remained open. Ciudad Juárez, with its 2,660 murders in 2009 out of 1.3 million residents, is the world’s most dangerous city outside a war zone. It also happens to be the main route for cocaine to Chicago. The Sinaloa Cartel, the country’s richest and most powerful, has recently attempted a violent takeover of the city from the Juárez Cartel, and the ensuing firefights have crippled infrastructure, closed business, and sent thousands fleeing into the U.S. for refuge. Seizure and extermination of drug supplies has produced similar increased violence amongst cartels, as they must fight for the remaining supplies and search for other alternative illegal activities.

As a result of army intervention and increased competition, the country’s various lords were forced to recruit new, outside members in order to increase their firepower, a sharp contrast to old rules of strict blood-relations employment. Los Zetas, a paramilitary group of 31 ex-Special Forces troops, were originally hired to protect an up-and-coming drug lord. The brutal tactics of these ex-soldiers have forced all other Mexican cartels to play a “murdering” catch-up of sorts. This, Rios believes, has produced a new type of beast: “Now we are seeing the emergence of a different drug trafficker. It is not the old, rural drug trafficker. These ones are younger, enjoy violence more, and are more entrepreneurial.”

Gone are the classic mobster days of respect for the unwritten rules, and paying the price are civilians and government officials. “The consequence of all of this,” Rios claims, “is that these guys are not only dealing drugs, but are kidnapping and extorting.”

Drugs are no longer the principal concern, according to Columbia history professor Pablo A. Piccato. The new widespread violence is a societal problem of which drugs play only one, albeit large, role. The city of Juárez provides a clear example of the other factors contributing to the new violence culture. 80,000 of Juárez’s youth neither study nor work. The industrial city is the site of inadequate schools, hospitals, and areas of public recreation. Almost 30 percent of the city’s businesses have closed their doors. Its police forces are steeped in corruption and over 100,000 citizens have fled the city in the last four years alone.

The most crucial institution in any of the rebuilding efforts, says Piccato, must be the nation’s judicial system. Since drug trafficking and violent crimes are under federal jurisdiction, local courts have little say over the corruption affecting their own communities. Moreover, trial is by judge, not jury, and with fewer judges on the federal circuit, the cartels are able to efficiently implement the law of “plata o plomo,” the choice that many judges face between accepting bribes or being killed. Any government initiatives that fail to include judiciary reform, Piccato notes, will result in nothing more than the army continuing patrolling the streets.

Initiatives by the Mexican government, however, stand little chance without broader U.S. efforts both at home and abroad. Domestically, the United States is one of the largest illicit drug markets in the world, and much of the competition between cartels is over access to our markets. Billions of U.S. dollars flow across the border into criminal pockets. Experts and politicians claim that 90 percent of the cartel weapons are purchased within the United States. With no efforts to reinstate the assault rifle ban in 2004 in sight, high-powered U.S. weapons will continue to flood the Mexican countryside.

American-related developments that have little direct effect on Americans tend to go unnoticed. But as violence has increasingly spilled over into the United States, American officials began to take more notice of the possible security threats arising from Mexico’s six northern states. Reported kidnappings in Phoenix, AZ, have tripled from 28 in 2004 to 368 in 2007. American citizens have been victims of extortion as gangs have targeted their relatives across the border. Illegal immigrants are being forced to carry drugs as payment for assistance in crossing the border. Turf wars have flared up in major U.S. cities such as Dallas, TX, leaving beheaded victims in their wake. American officials have expressed fears that border officials have become targets of bribes and extortion.

The first response to the new security threat was the 2007 Bush administration’s Merida Initiative, a three-year, $1.5 billion effort focused on providing advanced interception technology and the strengthening of law enforcement agencies. Though technological support was a necessary first step in fighting the new organizations, the 2007 agreement suffered from a noticeable lack of focus on domestic consumption by either Mexico or the United States. 40 percent of the funds were used for aircraft alone. Though money was allocated for law enforcement, there were no pressures for reform, and in a climate of systemic corruption, cash funds could only go so far. The plan was criticized last year by the Latin and American Commission on Drugs and Democracy, headed by former presidents from Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, who claimed that the United States needed to focus on drug users as a health, and not a criminal, problem.

Yet it seems that the Obama administration is finally taking the necessary step of breaking away from the socially conservative attitude of the last administration toward the war against drugs. After the recent deaths of U.S. consular worker Lesley A. Enriquez and her husband, Arthur H. Redelf, the White House sent the high-profile team of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Defense Secretary Robert Gates, and Department of Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano to Mexico City in order to revamp cooperation between the two countries. The result was an extension of the Merida Initiative to the tune of $331 million.

Rhetorically, the new declaration should be celebrated as a major and much-needed step in the war against drugs. The new extension of funds goes beyond the military focus and includes crucial funding for social programs and the court system. While police corruption has historically made U.S. officials wary of giving up intelligence, new “fusion centers” are being created to better combine the efforts of American agents and Mexican analysts. Finally, greater focus on monitoring the illicit cargo that gang members traffic between Mexican and American cities could do much to plug the porous border. Compared with the $18 billion to $39 billion in cartel profits from U.S. markets, American aid seems like a drop in the bucket, but it should be praised as the first step in tackling a bigger problem with a more ambitious agenda.

As the violence continues, Calderón’s government must still provide clear, short-term benefits for its constituency. Otherwise, attempts at long-term solutions could collapse before they can be fully implemented. But Calderón isn’t the only one who should be worried. If the Mexican population becomes fed up with its government’s failed attempts to provide greater security for its citizens and break the cartels, the implications for the United States could be enormous. As Rios duly notes, more breathing room for the drug gangs will mean a greater inflow of drugs into U.S. markets. More drugs create lower prices, and lower prices translates into more potential addicts, according to simple supply-and-demand laws. Moreover, as Juárez has shown, a breakdown of security could send hundreds of thousands across the border in search of safety in the United States.

The Obama administration needs to solve the international problem of drug violence with greater cooperation and demands for political and social betterment on the part of its allies. If the fountain of killings is not plugged now, the deluge could become unbearable in the near future.