Common (Non)sense

The Cold War may be long over, and capitalism is still basking in the glow of its successes (did someone say recession?), but another rather icy, oh-so-subtle battle is being waged within campuses across this great union. Beneath the edifice that proudly reads “The Special Relationship,” Americans are constantly belittling their British counterparts. Whilst I may shed a tear when you declare our empire dead, our importance dwindling, our prime minister obese and our children drunk—the fight back must begin. D-Day is here.

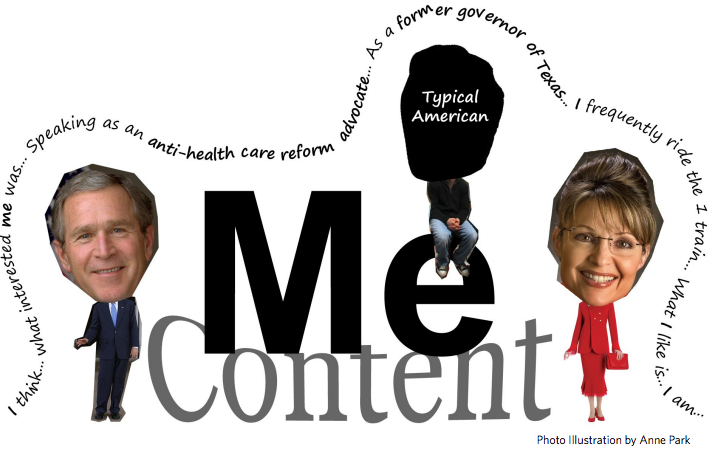

I could have begun this essay by copying a good old American student’s trick—announcing my esteemed self before the start of a sentence. It might have begun: “Speaking as an Englishman in New York...” But I refrained. Yanks seem to take pleasure in instantly placing themselves at the forefront of the conversation. Replies to questions in seminars always start with “What interested me was...” or “I guess what I was questioning in the piece was...” As a result, the subject of the discussion is pushed to the back, and the student becomes the focus.

Take this example of a professor posing a question to a student:

“So what role did journalists have in the shaping of the civil rights movement in Selma?”

“Well, what interested me, speaking as a Vermont-born, anti-healthcare reform advocate and Ayn Rand lover who frequently rides the 1 train...”

“Wait a minute, you’re from Vermont? I love it there!”

“Oh really, professor? Well let’s hop on the 4:42 Greyhound Express from Port Authority.”

“Awesome. I’ll bring The Fountainhead.”

What happened to the original question? It has been tossed aside and left to dry, a bit like mayoral two-term limits.

Yet this type of discourse even occurs at the highest levels of American society:

“President Bush, why was your reaction to Hurricane Katrina so delayed?”

“Well, speaking as a Texan cowboy who likes football and socializing...”

“Hey, Mr. President, do you want to cut this crap, get a beer and watch the game? I’ve always wanted a Corona with our commander-in-chief.”

“Yeah, sure, those wars can wait for now.”

This all comes down to the American love for the individual, which, for a Brit, is hard to grasp. In an ethics seminar a few days ago, the professor discussed at length the deficiencies of the BBC. He labelled it hierarchical and too much of an old gentlemen’s club. The BBC cheats, the professor argues; it gets its money from the tax-payer every year. Apparently, it’s some sort of state monopoly that actually causes the production of trashy TV.

But has the BBC set-up really been debilitating? Let’s take a minute to realize that the BBC is the one news organization that hasn’t been effected by the journalistic depression that has hit the industry. It’s still teeming with well-versed British intellectuals. The same could hardly be said for American media institutions. Dare I mention Glenn Beck?

But I digress somewhat. The American student’s need to insert the self into conversation reflects perfectly the American belief in the individual, and this is wherein their difference from their British counterparts lies. But it’s more nuanced than that: American society is embedded with an anti-intellectualism that deprives them of the sophistication of the plucky Brit. While admiring the individual is a worthwhile trait, Americans have always been taught to ignore superior individuals who could diminish their Yankee virility. Hence, in the late eighteenth century the English crown was defeated by such clever tactics as throwing tea boxes in the ocean. Now that really was below the belt: we invite you for a discussion about taxes over a quiet cup of tea, and you dispense of the beverage? That’s just not cricket. (For those of you who grew up on this side of the pond, that’s an English idiom referring to the refined etiquette of this most noble sport, where players break for “tea,” whereas baseball players break to dip tobacco and down 3000-calorie burritos).

Perhaps the American is plagued at night by the knowledge that the foundation of their constitution relies on Englishmen: Locke and Paine. Thus, in order to fudge the roots of the American ideal, they are constantly trying to refine English ideals into superior American ones. This attempt is valiant but, in the end, wildly unsuccessful. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was recently renovated by Glenn Beck in his new book, Glenn Beck’s Common Sense. In another instance, the Bush administration’s obstinacy to “stay the course” in Iraq was not unlike George III’s insistence on staying at war with American revolutionaries while his own advisors expressed hesitation. In the twenty-first century, the insurgents may be different, but the stubbornness is all the same.

Americans still haven’t learned their lesson.

The American sense of inferiority to the British bred individualism combined with anti-intellectualism, which has now created an unprecedented level of narcissism. It is plain to see in our respective governments; Gordon Brown is aware of his intelligence, but he doesn’t need to show off; he hides it behind the mask of a deflated and depressed Scotsman. President Obama however requires Greek columns and a rather stunning wife to show that he’s the leader of the free world.

This is the crux of the issue: the British people have always let their accent do the talking. The majority of us don’t put a premium on comportment—we leave that to the Royal Family, a dynasty rife with genetic disorder and inbred ignorance. Americans, on the other hand, are not about the content of discourse, they’re all about style. It doesn’t matter that in a seminar you make no sense; it’s about how you look good when you’re not making sense. That’s why last year’s decision by the GOP to spend $150,000 on Sarah Palin’s clothing should not be derided; it was a choice rooted in the noble American tradition.

Bring on 2012.