Adopting a New Tone

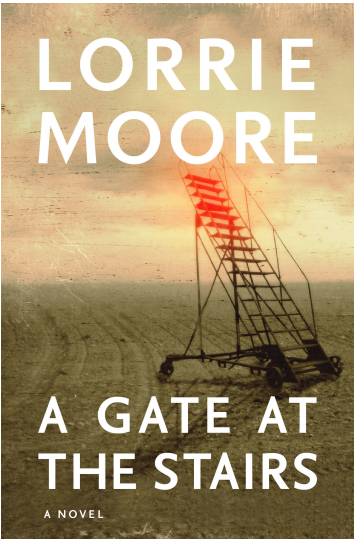

Lorrie Moore is one of America’s great contemporary writers, despite and because of her willingness to go silent. Moore’s admirers – this reviewer included—have been hankering for a new Moore book over the eleven years since her short story collection Birds of America. That book was laden with puns, extended-release metaphors, and at least three memorable characters. With her new novel, A Gate at the Stairs, Moore takes an unexpectedly blunt political turn, eschewing the wit and grace for which she had been appreciated. Moore’s literary odyssey demonstrates that there’s no better way to become a legend than by staying out of the limelight, and no worse way to disappoint than by stepping forward and revealing you have nothing to say.

To be fair, Moore’s absence from literature’s limelight did end a bit before A Gate at the Stairs. In June 2008, after Hillary Clinton had left the Presidential campaign, Moore wrote a brief, weird appreciation of Clinton for New York, filled with cloudy metaphors and contradictions. She compared Clinton to, alternately, an animated raccoon, Mick Jagger, and the witch in Snow White. A writer whose short stories largely deal with the neuroses young creative or academic types, often catalyzed by romantic misadventure, had been stymied. She writes that she became obsessed with the 2008 Democratic primaries and that friends jokingly (?) tried to get her to rehab. A Gate at the Stairs is a further manifestation of this obsession, proving that when dealing with issues in which one is engrossed, good art is not usually the end result.

Lorrie Moore is one of America’s great contemporary writers, despite and because of her willingness to go silent. Moore’s admirers – this reviewer included—have been hankering for a new Moore book over the eleven years since her short story collection Birds of America. That book was laden with puns, extended-release metaphors, and at least three memorable characters. With her new novel, A Gate at the Stairs, Moore takes an unexpectedly blunt political turn, eschewing the wit and grace for which she had been appreciated. Moore’s literary odyssey demonstrates that there’s no better way to become a legend than by staying out of the limelight, and no worse way to disappoint than by stepping forward and revealing you have nothing to say.

To be fair, Moore’s absence from literature’s limelight did end a bit before A Gate at the Stairs. In June 2008, after Hillary Clinton had left the Presidential campaign, Moore wrote a brief, weird appreciation of Clinton for New York, filled with cloudy metaphors and contradictions. She compared Clinton to, alternately, an animated raccoon, Mick Jagger, and the witch in Snow White. A writer whose short stories largely deal with the neuroses young creative or academic types, often catalyzed by romantic misadventure, had been stymied. She writes that she became obsessed with the 2008 Democratic primaries and that friends jokingly (?) tried to get her to rehab. A Gate at the Stairs is a further manifestation of this obsession, proving that when dealing with issues in which one is engrossed, good art is not usually the end result.

Indeed, A Gate at the Stairs simultaneously addresses issues of adoption, race, class, war, terrorism, and education, doing justice to none. Hardly afraid of overstuffing her book with plot, Moore incorporates into her story a college student who might be a terrorist and a young man shipped off to Afghanistan. These topics could alone be grist for a significantly longer book, but are here engaged only when the main action of the book runs dry. Moore is skittishly afraid of describing events too directly, and instead sets up a debate of sorts between two of her characters: Tassie Keltjin, a college student emotionally adrift, and Sarah Brink, the worst sort of liberal woman. Sarah vacillates between treating Tassie, her nanny, with too much intimacy and with high-handed disdain. Sarah doesn’t quite know the role a nanny or child should play in her life, nor the quagmire she’s getting into, though. This vacillation informs Moore’s decision to treat the entire adoption process with contempt. An unpleasant leitmotif sees adoption workers repeatedly reassuring Sarah as to the relative lightness of her prospective baby’s skin.

We know Sarah is unpleasantly liberal for several reasons. She lies to an adoption agency about her ability to work from home (she is – tsk! – a restaurateur, making indulgent dishes with herbs and angry, unladylike calls to her sous-chef), she feels comfortable calling her housekeeper “the cleaning gay” (and feels comfortable having a housekeeper, for that matter), and she adopts a mixed-race child and changes her name. Sarah is stunned to encounter racism in a town with “cruelty-free tofu,” which, as a buzzword for effete liberalism, simply lacks the wit for which Moore is so renowned. (Did “a town with lattes, Volvos, and The Nation” seem too subtle?) Conversely, We know Tassie is the salt of the earth because she observes all of these things in a plainspoken manner, ever-so-perplexed at just how Sarah runs her life. Moore is perplexed, too, and in her past writing, she always had a good handle on the characters she had created. Either Moore has lost her touch (this can’t quite be true as this book is, if nothing else, compulsively readable) or that she just neglected to make the older, liberal woman a human, leaving her instead a signifier, a raccoon-cartoon metaphor whose greatest significance lies within Moore’s mind.

There’s a mean streak of passive-aggression running through A Gate at the Stairs, largely hinging on the question of adoption. Moore has lost the warmth of her earlier works. Her short story in Birds of America about a pediatric oncology ward is one of the most empathetic works of fiction one could hope to read. Where did Moore’s belief that people are basically good go? Sarah means well, but she’s an utter failure as a mother, and melodramatically awful at child-rearing (in ways that, if described, would spoil the pulpy twists) that this novel becomes a sort of fantasy of what a certain breed of adoptive mothers are like. “We are pioneers... We are doing something important, unprecedented, and unbearably hard,” says Sarah, of raising a multiracial child in a white family.

Her husband jokes that they ought not call the girl Condoleezza, though Sarah considers naming her “Maya or Leontyne or Zora, something that honors the heritage of black women.” This novel is not a comedy – too many people die, there’s too much tense import attached to every thought that passes through Tassie’s mind – but Moore can’t be serious. Can she?

None of Sarah’s beliefs are necessarily wrong - adopting a child is fraught with challenges, though certainly few adoption advocates are so zealously, openly racist as those Tassie silently takes note of. The logic behind Sarah’s thoughts, which she always seems to blurt out, is nonexistent, though half the time, she’s a pie-in-the-sky optimist, and the other half, she’s unrealistically defensive of what is becoming a more and more common decision. If Moore’s agenda was to paint this decade’s liberals as vacillating even in their most altruistic decisions, she succeeded. Sweet Tassie isn’t so sophisticated: “I was tired and wasn’t exactly clear what Sarah was talking about,” she says, at the end of another of the endless string of Sarah soliloquies. And why should a novelist want to have a protagonist who feels anything more than exhaustion, who understands her milieu with clarity?

Moore is clear to a fault, though. Transparent, even. And when, at novel’s end, Sarah’s largely invisible husband resurfaces to (spoilers ahead!) ask Tassie on a date, his marriage having been crushed under the weight of Sarah’s isolating do-gooderism, Moore’s skewed understanding of the motives of adoptive parents, and her own motives in creating this novel, become even clearer. Moore is here to remind us What Really Matters: war, when Moore feels like talking about it.

Tassie’s major academic demand is a class on musical scores of war movies (Moore can still skewer academia well), and her brother is the novel’s soldier in Afghanistan. However, like the Brinks, he’s a mere puppet of the narrative, showing up and saying the right things so that Tassie may observe him and make cryptic pseudo-observations about American life. His thoughts, though, are treated with great respect by the novel, even though they’re as flimsy as the Brinks’ observations. When he dies, he leaves the novel in dignity; the Brinks survive, and storm out in disgrace.

The title of A Gate at the Stairs refers to a gate in the Brinks’ home, blocking access as a safety measure for their new baby, a sign of care that Tassie imbues with psychic significance. The gate blocks Tassie’s entry into the life of the home. Lacking access to the inner lives of the Brinks, their nanny feels free to think of their innocent actions as monstrous in the moments she chooses to share, the couple’s discomfort together and Sarah’s copying Tassie’s distinctive perfume. There’s no other dimension in which we have to view the Brinks but one that privileges plainspokenness over sophistication - and why is one inherently better than the other? Thus, we see the Brinks’ divorce, and the seizure of their child, as uncomfortable but right. Justice is served on the home front, even if it can’t be in America’s ongoing war.

Who knows what Lorrie Moore was hung up on in the eleven years it took her to complete A Gate at the Stairs, but one only hopes it is now out of her system, just as she purged her feelings about Hillary Clinton onto the pages of a magazine. An expansive novel taking on the way we live now should be a fair fight, at least. Pitting straw-man and -woman liberals against the power of Moore’s formidable wit and Tassie Keltjin’s insidiously winning innocence simply makes everyone looks bad.