Crossword Puzzle

“Indian peasants live in such a primitive way that communication is practically impossible… The price they must pay for integration is high-renunciation of their culture, their language; their beliefs, their traditions and customs, and the adoption of the culture of their ancient masters… Perhaps there is no realistic way to integrate our societies other than asking the Indians to pay that price…”- Mario Vargas Llosa

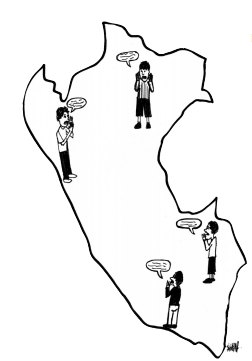

The debate over linguistic policy in Peru is as old as the conquest. In the 16th century, the Spanish used language to control the indigenous population by limiting its political participation. Making Spanish the official language of the government prevented indigenous people from accessing necessary political institutions and services like health care, police protection, and education—a disparity that continues even today. The ruling elite has thereby perpetuated its advantage over an undereducated and underserved class, and present economic growth has only exacerbated this inequality. Language barriers between Quechua-speaking producers and Spanish-speaking exporters, as well as between marginalized rural communities and the central government, continue to widen the income gap.

The debate over linguistic policy in Peru is as old as the conquest. In the 16th century, the Spanish used language to control the indigenous population by limiting its political participation. Making Spanish the official language of the government prevented indigenous people from accessing necessary political institutions and services like health care, police protection, and education—a disparity that continues even today. The ruling elite has thereby perpetuated its advantage over an undereducated and underserved class, and present economic growth has only exacerbated this inequality. Language barriers between Quechua-speaking producers and Spanish-speaking exporters, as well as between marginalized rural communities and the central government, continue to widen the income gap.

“Our country, Peru, doesn’t really develop,” explained Roody Cáceres Torres, advisor to Congresswoman María Sumire, “precisely because one great barrier is the language. [It is] a barrier for the exchange of products, for the sale of the same, for the production....” Peru lacks communication between the country’s ethnic groups, and it lacks the inclusion of the country’s most destitute sectors in national and global economic trends. At present, the ruling elite is characterized by its adherence to the Spanish language, which only the well-off classes tend to speak. Given that approximately 50% of the country still lives below or immediately above the poverty line—the same percentage that either lacks Spanish education or suffers from discrimination due to lack of Spanish fluency—the room for improvement is significant and the potential instability worrisome. But the situation remains the same as a vicious circle develops since these people are unable to obtain political power and hence do not intervene in the country’s management. In other words, the political elite do not voice the concerns of the country’s poorest, creating discontent and resentment. Recently, a populist presidential candidate brought the language issue to the forefront. In the 2006 election, opposition candidate Ollanta Humala obtained widespread support from the country’s poorest regions with a radical promise to require all Peruvians to learn indigenous languages. As much as Humala represented a radical approach, his reasons were fair. Two groups broadly characterize Peruvian society: the economically important, politically represented and relatively wealthy Spanish speakers, and the country’s larger population, which does not master Spanish and lives mostly in marginalized conditions in the country’s biggest cities, or in remote settlements deep in the mountains or the jungle. To Virginia Zavala, professor of sociolinguistics in Lima, “We are a country unable to imagine itself as a community.”

However, attempting to amend the situation by inverting the privileging of one language over another cannot be recommended. Such an inversion would most likely make the path to social and linguistic unification much harder: the tensions between the two groups, far from being ameliorated, would only be intensified as the most powerful political circles resisted such drastic change. The 2006 presidential elections evidenced Peru’s need for social inclusion in the future, but a more balanced overture, such as the educational policy suggested by the new law, would be more conducive to easing social tensions and attaining linguistic representation.

To address this issue, the Peruvian Congress is currently debating the Law for the Preservation and Use of Native Languages. Despite its alleged lack of specificity and support from certain factions of Congress, the law is a conscientious effort toward enfranchising hitherto marginalized communities and creating a more egalitarian society. Moreover—in contrast to its Constitutional predecessor, which named Quechua as an official language and stagnated thereafter—it aims to implement educational policies that promise a gradual reappraisal of the importance of indigenous languages in Peru.

The significance of linguistic representation transcends questions of political disenfranchisement and social stratification. At this moment, a fair linguistic legislation could greatly benefit Peru’s economic development. Not only would it appease the political climate, but it would also open markets to the country’s poorest. This means that a truly representative government would implement economic policies to include and protect those who are not currently prosperous. While the recent FTA agreement with the US, for instance, favors the higher social strata, it excludes the non-Spanish speakers. Better intra-country communication policies would foster a larger and more competitive internal market.

The law in question tackles precisely this issue of inequality by language discrimination. Title I of the law declares “specify[ing] the scope of individual and collective rights and guarantees” as its object. These rights, already established in Article 48 of the Constitution, give Quechua and other indigenous languages the status of official languages “in the zones in which they predominate.” The vagueness of this description, however, has previously made the law impossible to observe. While the new law does not aim to bestow new rights upon the affected citizens, it does aim to redefine previous legislation to make it effective in extending pre-existing rights and privileges—including access to institutions of power—to non-Spanish speakers or speakers of Spanish as a second language.

The specific issue of linguistic rights predominates in the fourth article of the law. “Every person,” it states, “and every linguistic community has the right to ... be attended in his/her/its maternal language ... in State Organizations or Instances....” This key point, which demands that non-Spanish speaking persons be attended in their maternal language, could expand access to the basic medical or police services that have been unavailable to second Spanish speaking Peruvians.

The implementation of such an ambitious policy, however, remains far from certain, inspiring several debates. In one session, Congresswoman María Balta Salazar raised the question, “How are we going to make the translation and publication of legal codes so that the villagers can know and understand them if these same villagers don’t even know how to write their own language?” To address this query, the law includes a requirement for oral translation in addition to written translation. Additionally, the law outlines specific rights to bilingual and bicultural education. Title I, Article 4, for example, stipulates rights “To receive education in one’s mother tongue and in one’s own culture, with an intercultural focus” and “To learn Spanish as the language of common usage in the Peruvian territory.” Further on, the law proclaims that the State should guarantee and promote the teaching of indigenous languages at all levels of schooling, rendering such objections obsolete in the future.

The emphasis on the intercultural aspect of education seeks to address the problem of disorientation, which arises, for instance, when children who live and work on a rural farm are taught in Spanish about airports, airplanes, and other concepts that might be unfamiliar. Bilingual, bicultural education also intends to minimize the discrimination suffered by many children who have a distinct Andean accent or employ malapropisms rooted in an incomplete education. Many of these children can avoid being held back in school from failing math or science by learning the concepts in a language they are comfortable with, before being exhorted to understanding them in the nation’s dominant language.

Advocates of the law go as far as stating that more than closing the gap between elite Spanish speakers and disadvantaged indigenous language speakers, a bilingual-bicultural education “disseminates the patrimony and oral tradition of Peru as the essence of the cosmovision and identity of the native cultures of the country, with the goal of raising awareness of the importance of being a pluricultural and multilingual country and to foment a culture of dialogue and tolerance.”

Although there are many obstacles to Peru’s becoming a developed country, one of the greatest barriers is the linguistic divide within the nation itself, which perpetuates socioeconomic inequality. By addressing the linguistic basis of this class divide, the new Law for the Preservation and Use of Native Languages promises to close the gap between the Peruvian elite and the rest of the country, eventually leading to unification and economic growth. It is therefore imperative that the Peruvian Congress expedite its approval rather than—once again—filing it in the archives of oblivion.