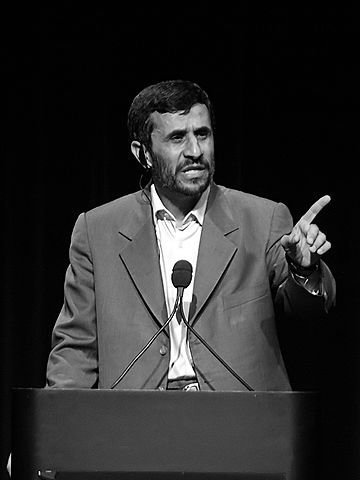

Nuclear Patriotism

It is easy to write off Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as a leader lacking in diplomatic skills and refinement, or, in less elegant prose, as a lunatic. Though his uncouth behavior seems outrageous to many Americans, Ahmadinejad actually appears to be playing his cards right in terms of his interests. His aggressive and inflammatory anti-Western rhetoric has united his nation behind him, a major feat, given Iran’s numerous oppositional reform movements. Whether or not Iran intends its nuclear program for energy or for weapons, Ahmadinejad has utilized international debate to silence domestic opposition, promoting nationalistic pride to rally Iranians behind the government.

Almost 30 years after the 1979 Revolution, the Islamic Republic of Iran has failed to deliver the promise of a free, liberal society. Democratic ideals of freedom and self-governance have remained elusive for those who joined the revolution to end the monarchical rule of the Shah and establish a democratic society. Many groups emerged out of discontent for what the revolution actually brought: a totalitarian regime ruled by clerics and an unelected Supreme Leader behind a façade of presidential democracy. Intellectuals, students, and women have formed groups in the hopes of effecting change in the Iranian government.

It is easy to write off Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as a leader lacking in diplomatic skills and refinement, or, in less elegant prose, as a lunatic. Though his uncouth behavior seems outrageous to many Americans, Ahmadinejad actually appears to be playing his cards right in terms of his interests. His aggressive and inflammatory anti-Western rhetoric has united his nation behind him, a major feat, given Iran’s numerous oppositional reform movements. Whether or not Iran intends its nuclear program for energy or for weapons, Ahmadinejad has utilized international debate to silence domestic opposition, promoting nationalistic pride to rally Iranians behind the government.

Almost 30 years after the 1979 Revolution, the Islamic Republic of Iran has failed to deliver the promise of a free, liberal society. Democratic ideals of freedom and self-governance have remained elusive for those who joined the revolution to end the monarchical rule of the Shah and establish a democratic society. Many groups emerged out of discontent for what the revolution actually brought: a totalitarian regime ruled by clerics and an unelected Supreme Leader behind a façade of presidential democracy. Intellectuals, students, and women have formed groups in the hopes of effecting change in the Iranian government.

But the stronghold of the Supreme Leader and the ruling clerics has held down many of these groups. Leading dissidents such as Akbar Ganji, who was repeatedly jailed for his views, and even the former reformist President Mohammad Khatami were unable to subvert the clerics. The expediency and brutality with which the Revolutionary Guards suppress student riots have stifled all public expressions of dissent.

In 2005, with the support of the Revolutionary Guards, Hezbollah, and some disillusioned reformists, the more conservative Ahmadinejad became president. The reformists who helped Ahmadinejad win the presidency put socio-political change on hold in exchange for Ahmadinejad’s promised economic reforms. In his first 15 months as president, Ahmadinejad has shown few signs of any intention to deliver on these proposed reforms, following Iranian rulers’ tradition of failed promises.

In order to take pressure off the presidency and unite a country full of discontented citizens, Ahmadinejad has raised his profile on the international stage, using the nuclear debate to lead a wave of patriotism that has silenced internal opposition to the government. Whether or not this was a primary motive for using such heated rhetoric, as Columbia professor of history Richard Bulliet said, “Talking big on the nuclear issue has captured the imagination of the Iranian people.”

Iran’s nuclear program is hardly Ahmadinejad’s innovative idea; long before his election, it had been revealed that Iran concealed its nuclear ambitions from the United Nations. The program started under the Shah in the 1970s, with its progress accelerating in the past 10 years. That Iran failed to disclose much about its program during these years has led the UN to doubt the innocence of the program.

The terms of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, however, give Ahmadinejad a strong legal ground in his charge that Iran retains the right to pursue a nuclear program. The treaty states that every signatory has a right to a peaceful nuclear energy program so long as it complies with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and its safeguards. Columbia professor of international politics Robert Jervis said that “legally, [Ahmadinejad] is right.”

Many Western nations claim Iran’s program will be used for weapons proliferation, and they cite Iran’s non-compliance with the IAEA’s safeguards as evidence. Countering these claims, Ahmadinejad has pointed to the hypocrisy of a treaty that did not stop other countries such as such as Israel and Pakistan from acquiring and maintaining nuclear weapons.

Ahmadinejad showed great political skill in his ability to seize the opportunity and use it to his advantage. In a speech to a group of students and clerics on November 22, 2006, the Iran Daily reported Ahmadinejad as calling for the “administration of justice” via “a national will,” proclaiming that, “today, a number of selfish and bullying powers are trying to plunder the wealth and resources of other nations.” Ahmadinejad has gained support for admonitions like this one, both from those within Iran who agree with his anti-imperialist rhetoric, and also from other third world nations that consider themselves to be victims of Western bullying and injustice. Despite perceptions of Ahmadinejad in the West, he has the support of many nations that empathize with what they perceive as Iran’s victimization by the West. Both internally and in some international circles, Ahmadinejad has won support with his nuclear rhetoric.

Thanks to his success in unifying Iran’s many oppositional factions—in part by pushing the need to solidify Iran’s national sovereignty—Ahmadinejad has put himself in a position of great power. Surrounded by American troops and observing America’s proactive policy of regime-change in Iraq from nearby, most Iranians, including the reformists, are undoubtedly interested in the question of national sovereignty. The appeal for nuclear power as a deterrent is perhaps a logical extension of these anxieties. A number of dissident factions have once again put differences aside to stand behind what they see as the best interest of Iran.

The nuclear debate is a powerful source of nationalistic pride. Many Iranians feel that it is their nation’s right to have a peaceful nuclear energy program (or even weapons) and that they are being treated unjustly. In invoking this patriotic pride, Ahmadinejad uses history to support his narration of Iran’s constant victimization by the West. As Iran expert and Columbia professor Hamid Dabashi points out, Ahmadinejad has “connected the nuclear issue with colonial abuses of natural resources.” Ahmadinejad likens the current US trend toward regime-change to the 1953 coup orchestrated by the CIA to protect American interests in Iran. He has tapped into the same type of nationalism by resurrecting the anti-Western jargon that rallied support behind Ayatollah Khomeini in the 1979 revolution.

“The issue of nuclear energy (and potentially nuclear arms) has already become a matter of national pride for Iranians, and people across a wide range of the political divide vociferously endorse it,” Dabashi wrote in an April 2005 editorial.

Ahmadinejad’s tendency to enrage the international community, and specifically the US, puts Iran’s reformists on the defensive. It becomes hard for them to find a platform whereby they do not appear to support American ambitions in the region. Ahmadinejad repeatedly paints them as unpatriotic or as supporters of foreign invasion. With few alternatives, the already dispirited and disorganized reformists have allied themselves behind the government or have become fragmented.

Ahmadinejad has played the political game successfully. It is possible that in the end his goal is more regional than national: to be the dominant power in a war-torn region and to be a major player in the international arena with nuclear weapons. Despite what his ultimate desires may be, “by almost any scenario, Iran has come out ahead,” Bulliet notes. The leading oppositional reform movements are on the defensive, desperate to detach themselves from a seeming advocacy of the imperialist West.

Internationally, Ahmadinejad has explicit support from the leadership in Syria and Venezuela and public support in many other countries. Baiting the US seems to have proven popular: the more stringent the US policies, the more Iranians become attracted to nationalism, nuclear ambitions and the fight against the West.